Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

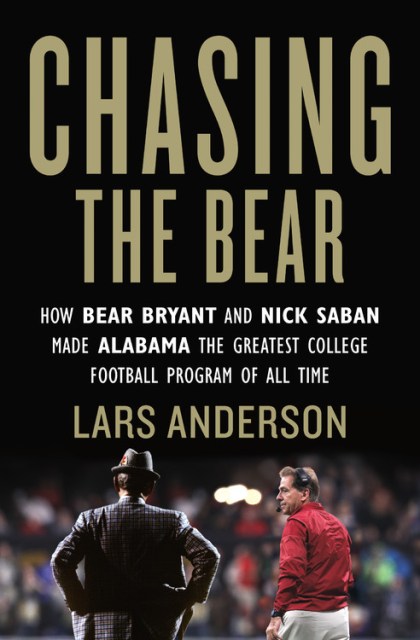

Chasing the Bear

How Bear Bryant and Nick Saban Made Alabama the Greatest College Football Program of All Time

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 15, 2020

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781538716472

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 15, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A dual biography of two coaching legends — Bear Bryant and Nick Saban — who built the Alabama Crimson Tide into a true football dynasty.

Both Bear Bryant and Nick Saban are undeniable kings of college football, two coaches at Alabama who have each won more national championships — six apiece — than anyone else in the history of the game. CHASING THE BEAR examines how they did it, revealing along the way their similarities in style, background, football philosophy, and recruiting methods, while providing readers a rare inside look at two of the greatest leaders in the history of sports.

Bear Bryant and Nick Saban never met, but they have more in common than either of them realize. Both grew up in small towns — Bryant in Moro Bottom, Arkansas, a dot on the map, and Saban from Monongah, West Virginia, population five hundred. As a child, Saban pumped gas at his father’s service station, washing and waxing cars and doing anything he could to help the business. Bryant’s father suffered from multiple physical ailments, which forced Bryant to work to keep the family farm going. Both men knew the value of hard work from the time they were young boys, and both understood that there were no shortcuts to success. But both dreamed of escaping their hometowns, and both used football as the means to do so.

Separated by two generations, Bear Bryant and Nick Saban are mythic figures linked by a school, a town, and a barroom debate centering on one question: Which is the greatest college coach of all time?

Bear Bryant and Nick Saban never met, but they have more in common than either of them realize. Both grew up in small towns — Bryant in Moro Bottom, Arkansas, a dot on the map, and Saban from Monongah, West Virginia, population five hundred. As a child, Saban pumped gas at his father’s service station, washing and waxing cars and doing anything he could to help the business. Bryant’s father suffered from multiple physical ailments, which forced Bryant to work to keep the family farm going. Both men knew the value of hard work from the time they were young boys, and both understood that there were no shortcuts to success. But both dreamed of escaping their hometowns, and both used football as the means to do so.

Separated by two generations, Bear Bryant and Nick Saban are mythic figures linked by a school, a town, and a barroom debate centering on one question: Which is the greatest college coach of all time?