By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

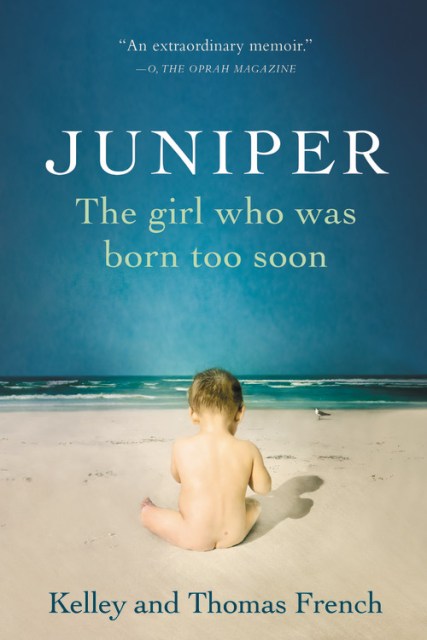

Juniper

The Girl Who Was Born Too Soon

Contributors

By Thomas French

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 10, 2017

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316324434

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 10, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A micro-preemie fights for survival in this extraordinary and gorgeously told memoir by her parents, both award-winning journalists.

Juniper French was born four months early, at 23 weeks’ gestation. She weighed 1 pound, 4 ounces, and her twiggy body was the length of a Barbie doll. Her head was smaller than a tennis ball, her skin was nearly translucent, and through her chest you could see her flickering heart. Babies like Juniper, born at the edge of viability, trigger the question: Which is the greater act of love — to save her, or to let her go?

Kelley and Thomas French chose to fight for Juniper’s life, and this is their incredible tale. In one exquisite memoir, the authors explore the border between what is possible and what is right. They marvel at the science that conceived and sustained their daughter and the love that made the difference. They probe the bond between a mother and a baby, between a husband and a wife. They trace the journey of their family from its fragile beginning to the miraculous survival of their now thriving daughter.

Juniper French was born four months early, at 23 weeks’ gestation. She weighed 1 pound, 4 ounces, and her twiggy body was the length of a Barbie doll. Her head was smaller than a tennis ball, her skin was nearly translucent, and through her chest you could see her flickering heart. Babies like Juniper, born at the edge of viability, trigger the question: Which is the greater act of love — to save her, or to let her go?

Kelley and Thomas French chose to fight for Juniper’s life, and this is their incredible tale. In one exquisite memoir, the authors explore the border between what is possible and what is right. They marvel at the science that conceived and sustained their daughter and the love that made the difference. They probe the bond between a mother and a baby, between a husband and a wife. They trace the journey of their family from its fragile beginning to the miraculous survival of their now thriving daughter.

-

"Raw, rough and wrenchingly tender....An almost universal story of love and determination and strength."USA Today

-

"An extraordinary memoir."O, the Oprah Magazine

-

"Beautifully written...it will stay with you long after you finish."Good Housekeeping

-

"Riveting."Tampa Bay Times

-

"This book is a tender, fierce and breathtaking miracle."People

-

"Two skilled journalists collaborate on the most personal of stories: their extremely premature daughter's struggle to survive....A fierce and fact-filled love story with few holds barred."Kirkus Reviews

-

"I probably would have read Juniper in one sitting, but I had to stop because I was crying too hard....The Frenches make their fear, panic and grief real....A well-told, fast-paced and emotionally affecting memoir."Terri Rupar, Washington Post

-

"A twisting, harrowing, at times painful but powerful memoir, fiercely reported and written with exquisite sensitivity and openness."Dallas News

-

"[A] mom must-read....Juniper will capture your attention and heart from its difficult beginning to its hard-won happy ending."Parents

-

"The Frenches put forth a love story about their daughter, with highs and lows throughout and moments of sheer joy that will keep readers involved until the very last page. This achingly tender memoir is also a roller-coaster....The narrative sparks a need to reassess the meaning of a miracle, and the story will resonate for days after the last word. With sharp prose, honoring the simple and the profound, this book should be in the hands of every parent--indeed, of everyone."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"This is what happens when two great writers join together to tell something really worth telling. This book, of a life barely there, breaks your heart on one page, and makes you want to pump your fist in the air just a few paragraphs later. It is an achingly lovely book, all the lovelier because it is true."Rick Bragg, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist

-

"This surprising, enlightening book transcends categories. Heartfelt as a memoir, richly researched as narrative journalism, and as propulsive and literary as a novel, JUNIPER offers the rewards of all great books. It alters and expands your understanding of being human."Sheri Fink, author of Five Days at Memorial

-

"This tender and ferocious book offers all of the taut, gritty storytelling of the journalists who wrote it--and all of the lovesick hope of the parents they're becoming. I read it cover-to-cover in a single breathless, nail-bitten evening."Catherine Newman, author of Catastrophic Happiness and Waiting for Birdy

-

"Kelley and Thomas French are two of America's best narrative journalists, and here is their most important story yet. JUNIPER is an astonishingly intimate and honest account of a mother, a father, and a complicated baby whose very existence calls into question every easy assumption about what a life means. This is a deeply moving and meaningful book."David Finkel, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of Thank You for Your Service

-

"These two excellent journalists bring their keen eyes to the most personal and wrenching of stories. A powerful book."Tracy Kidder

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use