By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

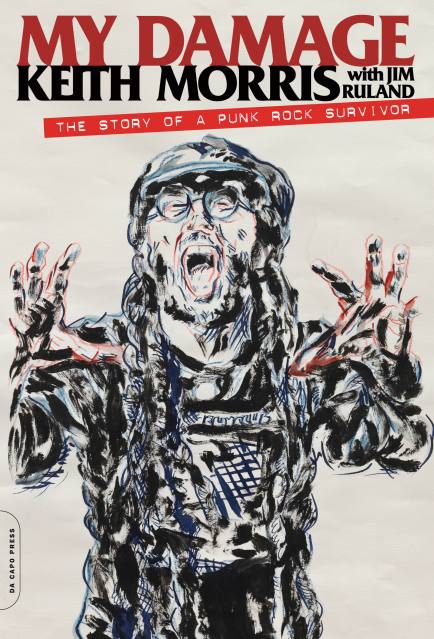

My Damage

The Story of a Punk Rock Survivor

Contributors

By Keith Morris

With Jim Ruland

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 5, 2017

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306825804

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 5, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

My Damage is more than a book about the highs and lows of a punk rock legend. It’s a story from the perspective of someone who has shared the stage with just about every major figure in the music industry and has appeared in cult films like The Decline of Western Civilization and Repo Man. A true Hollywood tale from an L.A. native, My Damage reveals the story of Morris’s streets, his scene, and his music-as only he can tell it.

-

"A compelling, unexpectedly moving, and all-around badass memoir."--Esquire

-

"My Damage is characterized by sharp wit, abundant empathy, and the wisdom of a man who has outrun his many demons."--MOJO

-

"A winning memoir from a punk icon"--A.V. Club

-

"A portrait of a famed frontman that is complex but earnest"--PunkNews.org

-

"An insightful and expansive look at an unconventional life"Men's Journal, 10/27/1

-

"A wild tell-all told in a no-holds-barred style, My Damage is an epic autobiography told with humor, honesty, and courage."The Good Men Project, 11/15/16

-

"Morris' book benefits from the same energetic, frenetically authentic style that makes his music so memorable. His description of the early punk scene and the inception of his two most famous bands is a fascinating read."Under the Radar, 11/18/16

-

"[My Damage] delivers the behind-the-scenes kind of stuff we all love reading in rock autobiographies."No Echo

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use