Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

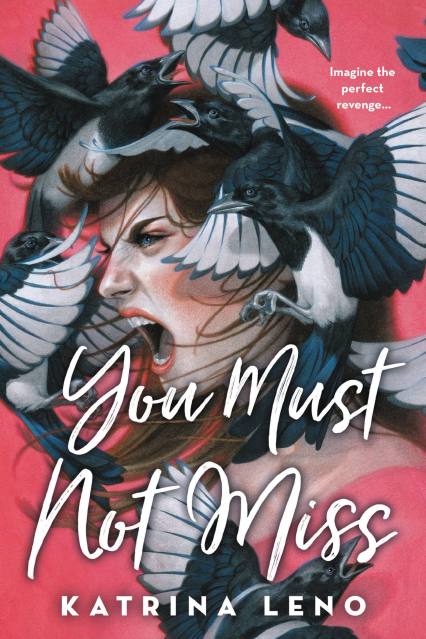

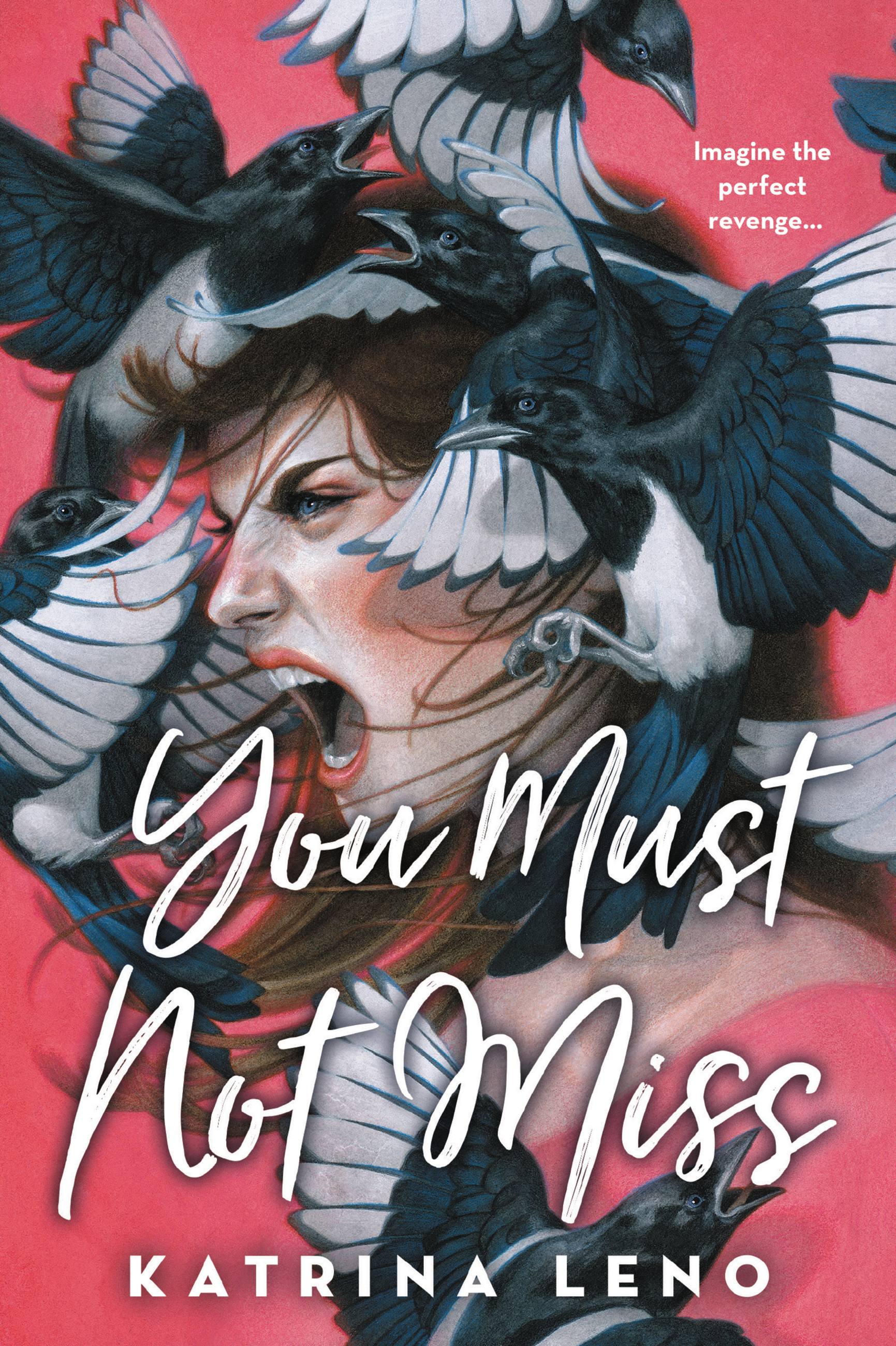

You Must Not Miss

Contributors

By Katrina Leno

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $11.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $10.99 $14.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 23, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

One of Us Is Lying meets Carrie in this suspenseful story of friendship, family, and revenge.

Magpie Lewis started writing in her yellow notebook the day after her family self-destructed. The day her father ruined her mother's life. The day Magpie's sister, Eryn, skipped town and left her to fend for herself. The day of Brandon Phipp's party.

Now Magpie is called a slut in the hallways of her high school, her former best friend won't speak to her, and she spends her lunch period with a group of misfits who've all been as socially exiled as she has. And so, feeling trapped and forgotten, Magpie retreats to her notebook, dreaming up a magical place called Near.

Near is perfect – a place where her father never cheated, her mother never drank, and Magpie's own life never derailed so suddenly. She imagines Near so completely, so fully, that she writes it into existence, right in her own backyard. At first, Near is a peaceful escape, but soon it becomes something darker, somewhere nightmares lurk and hidden truths come to light. Soon it becomes a place where Magpie can do anything she wants…even get her revenge.

You Must Not Miss is an intoxicating, twisted tale of magic, menace, and the monsters that live inside us all.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 23, 2019

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9780316449809

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use