By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

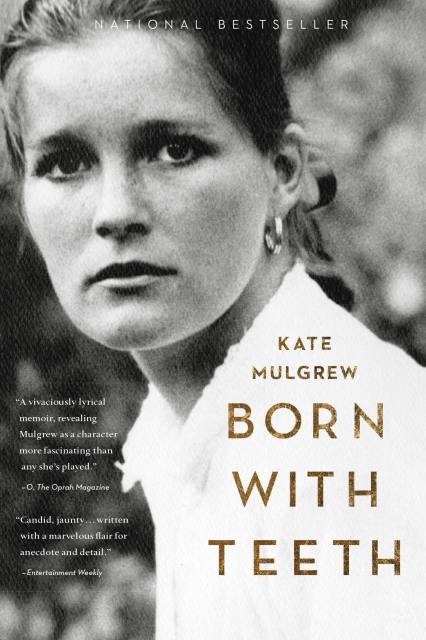

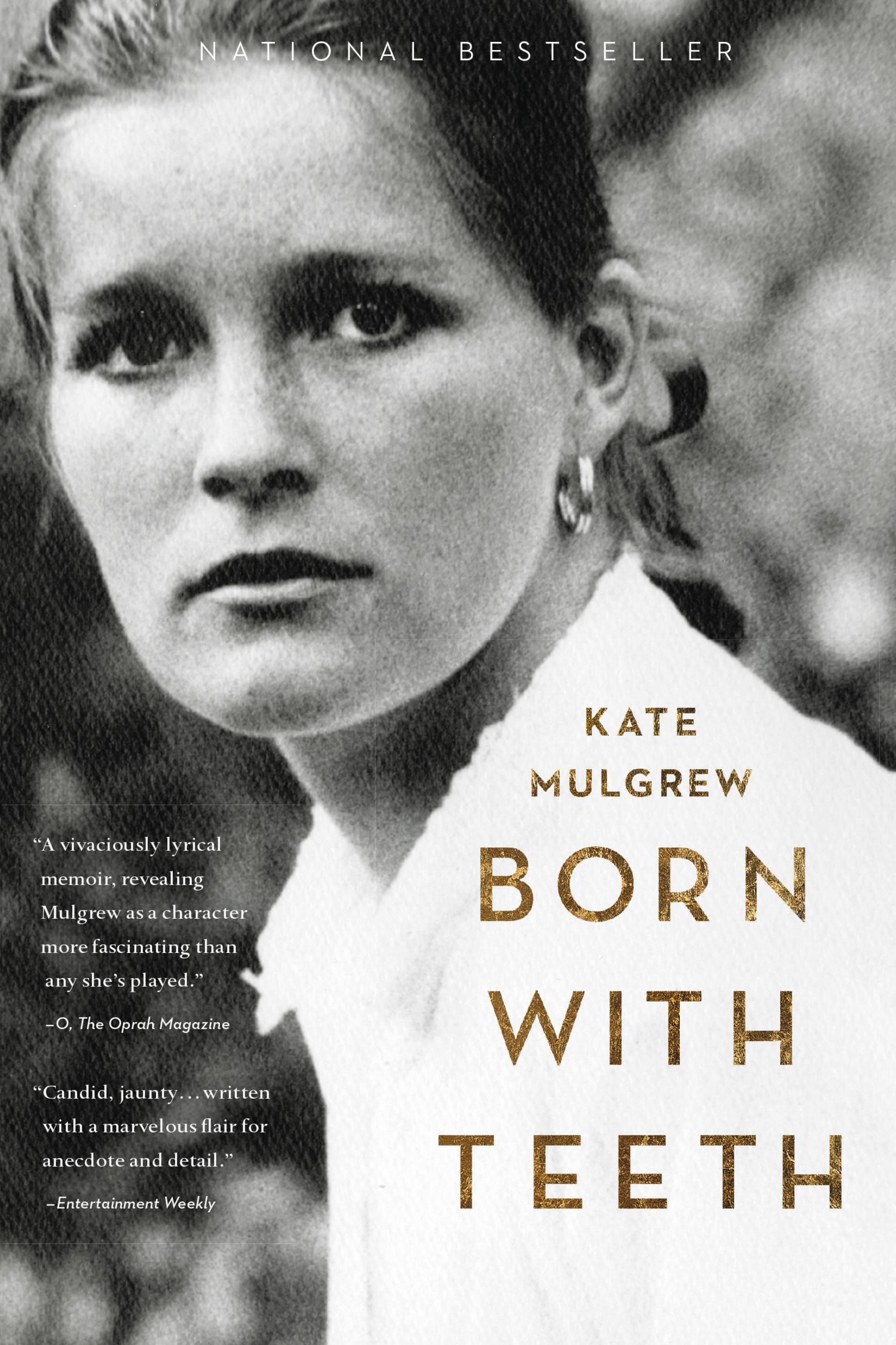

Born with Teeth

A Memoir

Contributors

By Kate Mulgrew

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 14, 2015

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316334303

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 14, 2015. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Determined to pursue her own no matter the cost, at 18 she left her small Midwestern town for New York, where, studying with the legendary Stella Adler, she learned the lesson that would define her as an actress: “Use it,” Adler told her. Whatever disappointment, pain, or anger life throws in your path, channel it into the work.

It was a lesson she would need. At twenty-two, just as her career was taking off, she became pregnant and gave birth to a daughter. Having already signed the adoption papers, she was allowed only a fleeting glimpse of her child. As her star continued to rise, her life became increasingly demanding and fulfilling, a whirlwind of passionate love affairs, life-saving friendships, and bone-crunching work. Through it all, Mulgrew remained haunted by the loss of her daughter, until, two decades later, she found the courage to face the past and step into the most challenging role of her life, both on and off screen.

We know Kate Mulgrew for the strong women she’s played — Captain Janeway on Star Trek ; the tough-as-nails “Red” on Orange is the New Black. Now, we meet the most inspiring and memorable character of all: herself. By turns irreverent and soulful, laugh-out-loud funny and heart-piercingly sad, Born with Teeth is the breathtaking memoir of a woman who dares to live life to the fullest, on her own terms.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use