By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

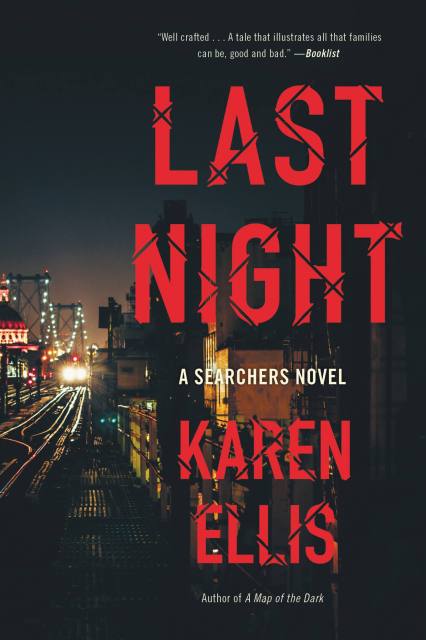

Last Night

Contributors

By Karen Ellis

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 26, 2019

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316505710

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $15.99 $21.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 26, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

NYPD detective Lex Cole tracks a missing Brooklyn teen whose bright future is endangered by the ghosts of his unknown father’s past, in this highly anticipated sequel to A Map of the Dark.

One of the few black kids on his Brighton Beach block, Titus “Crisp” Crespo was raised by his white mother and his Russian grandparents. He has two legacies from his absent father, Mo: his weird name and his brown skin. Crisp has always been the odd kid out, but a fundamentally good kid, with a bright future.

One of the few black kids on his Brighton Beach block, Titus “Crisp” Crespo was raised by his white mother and his Russian grandparents. He has two legacies from his absent father, Mo: his weird name and his brown skin. Crisp has always been the odd kid out, but a fundamentally good kid, with a bright future.

But one impulsive decision triggers a horrible domino effect–an arrest, no reason not to accompany his richer, whiter friend Glynnie on a visit to her weed dealer, and a trip onto his father’s old home turf where he’ll face certain choices he’s always strived to avoid.

As Detective Lex Cole tries to unravel the clues from Crisp’s night out, they both find that what you don’t know about your past can still come back to haunt you.

As Detective Lex Cole tries to unravel the clues from Crisp’s night out, they both find that what you don’t know about your past can still come back to haunt you.

Series:

-

"[An] existential thriller... Last Night is a group character study that offers realistic suspense. Ms. Ellis is an able guide inside the psyches of her subjects."Tom Nolan, Wall Street Journal

-

"Without resorting to stereotypes, Ellis deftly shows just how different the stakes are for kids who supposedly live in the same world but who face very different obstacles and possibilities. This thoughtful entry in the Searchers series will satisfy fans of the previous work as well as those who enjoy a well-crafted look at New York's underbelly."Booklist

-

PRAISE FOR KAREN ELLIS and A MAP OF THE DARKLiterary Hub

"Elegant, haunting... a far-from-ordinary FBI novel."

-

Alison Gaylin, USA Today bestselling author of What Remains of Me

"One of the most compelling psychological thrillers I've read in a long time, A Map of the Dark grabs you from the very first page and does not loosen its grip. I read this book in a day---I simply could not put it down---but I will be thinking about it for much longer." -

"A taut, tense, exciting read with a sharp and very human protagonist."Reed Farrel Coleman, New York Times bestselling author of What You Break

-

"Karen Ellis entwines complex storylines with breakneck precision. A must-read for fans of taut, unpredictable psychological suspense."Wendy Corsi Staub, bestselling author of Blue Moon

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use