By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

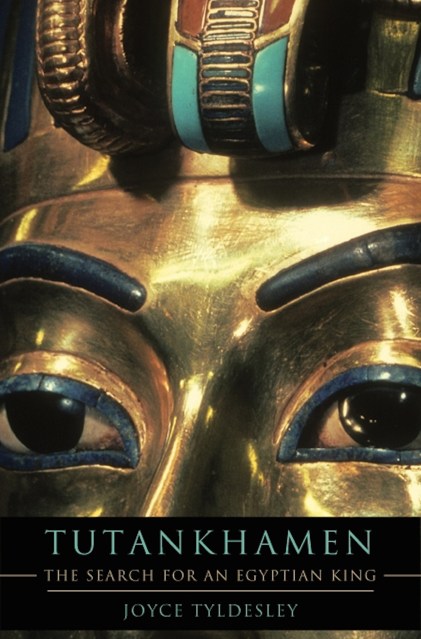

Tutankhamen

The Search for an Egyptian King

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 6, 2012

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465029358

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- Hardcover $39.00 $49.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 6, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Tutankhamen ascended to the throne at approximately eight years of age and ruled for only ten years. Although his reign was brief and many of his accomplishments are now lost to us, it is clear that he was an important and influential king ruling in challenging times. His greatest achievement was to reverse a slew of radical and unpopular theological reforms instituted by his father and return Egypt to the traditional pantheon of gods. A meticulous examination of the evidence preserved both within his tomb and outside it allows Tyldesley to investigate Tutankhamen’s family history and to explore the origins of the pervasive legends surrounding Tutankhamen’s tomb. These legends include Tutankhamen’s “curse” — enduring myth that reaffirms the appeal of ancient magic in our modern world

A remarkably vivid portrait of this fascinating and often misunderstood ruler, Tutankhamen sheds new light on the young king and the astonishing archeological discovery that earned him an eternal place in popular imagination.