By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

The Healing Power of Mindfulness

A New Way of Being

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 20, 2018

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780316522052

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 20, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

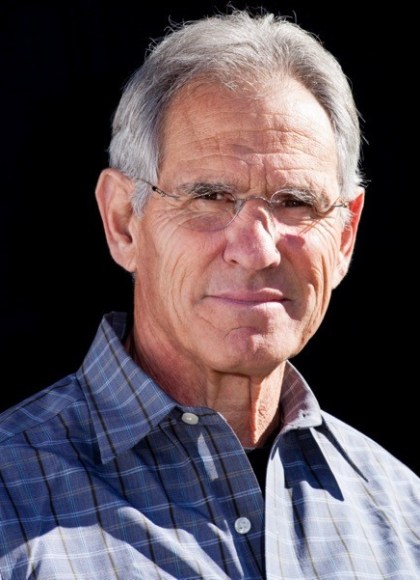

More than twenty years ago, Jon Kabat-Zinn showed us the value of cultivating greater awareness in everyday life with his now-classic introduction to mindfulness, Wherever You Go, There You Are. Now, in TheHealing Power of Mindfulness, he shares a cornucopia of specificexamples as to how the cultivation of mindfulness can reshape your relationship with your own body and mind–explaining what we’re learning about neuroplasticity and the brain, how meditation can affect our biology and our health, and what mindfulness can teach us about coming to terms with all sorts of life challenges, including our own mortality, so we can make the most of the moments that we have.

Originally published in 2005 as part of a larger book titled Coming to Our Senses, The Healing Power of Mindfulness features a new foreword by the author and timely updates throughout the text. If you are interested in learning more about how mindfulness as a way of being can help us to heal, physically and emotionally, look no further than this deeply personal and also “deeply optimistic book, grounded in good science and filled with practical recommendations for moving in the right direction” (Andrew Weil, MD), from one of the pioneers of the worldwide mindfulness movement.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use