Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

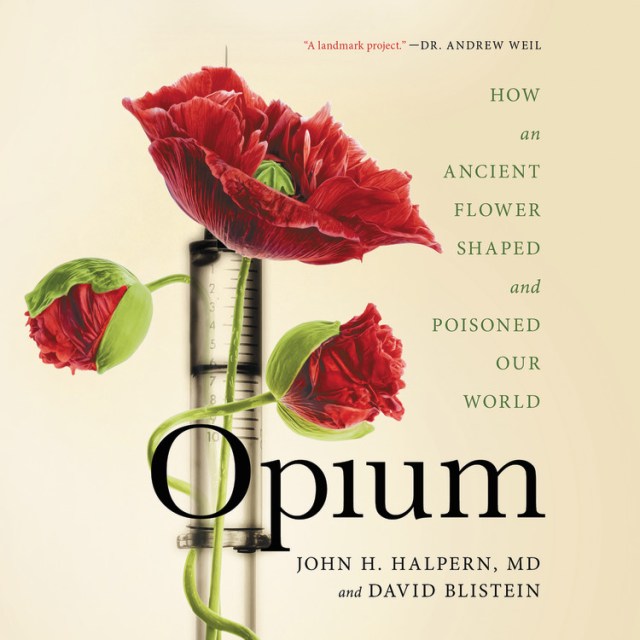

Opium

How an Ancient Flower Shaped and Poisoned Our World

Contributors

By David Blistein

Read by Peter Ganim

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 13, 2019

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549175329

Price

$24.99Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 13, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From a psychiatrist on the frontlines of addiction medicine and an expert on the history of drug use comes the “authoritative, engaging, and accessible” history of the flower that helped to build (Booklist) — and now threatens — modern society.

Opioid addiction is fast becoming the most deadly crisis in American history. In 2018, it claimed nearly fifty thousand lives — more than gunshots and car crashes combined, and almost as many Americans as were killed in the entire Vietnam War. But even as the overdose crisis ravages our nation — straining our prison system, dividing families, and defying virtually every legislative solution to treat it — few understand how it came to be.

Opium tells the “fascinating” (Lit Hub) and at times harrowing tale of how we arrived at today’s crisis, “mak[ing] timely and startling connections among painkillers, politics, finance, and society” (Laurence Bergreen). The story begins with the discovery of poppy artifacts in ancient Mesopotamia, and goes on to explore how Greek physicians and obscure chemists discovered opium’s effects and refined its power, how colonial empires marketed it around the world, and eventually how international drug companies developed a range of powerful synthetic opioids that led to an epidemic of addiction.

Throughout, Dr. John Halpern and David Blistein reveal the fascinating role that opium has played in building our modern world, from trade networks to medical protocols to drug enforcement policies. Most importantly, they disentangle how crucial misjudgments, patterns of greed, and racial stereotypes served to transform one of nature’s most effective painkillers into a source of unspeakable pain — and how, using the insights of history, state-of-the-art science, and a compassionate approach to the illness of addiction, we can overcome today’s overdose epidemic.

This urgent and masterfully woven narrative tells an epic story of how one beautiful flower became the fascination of leaders, tycoons, and nations through the centuries and in their hands exposed the fragility of our civilization.

An NPR Best Book of the Year

“A landmark project.” — Dr. Andrew Weil

“Engrossing and highly readable.” — Sam Quinones

“An astonishing journey through time and space.” — Julie Holland, MD

“The most important, provocative, and challenging book I’ve read in a long time.” — Laurence Bergreen

Genre:

-

"Wealthy patrons of the arts making fortunes off opioids? Blaming immigrants for a domestic drug crisis? Race-based enforcement?...It was as true in the 19th and 20th centuries as it is today. Opium insists that we take an unstinting look at the relationship between people and opioids and dares us to make the hard decisions necessary to deal with the crisis. This book is what history is supposed to be."Ken Burns, filmmaker

-

NPR, Best Books of the YearScientific American, Editors' PickNature, Picks of the WeekLit Hub, Books of the Week

-

"In this landmark project, John Halpern, MD, and David Blistein have for the first time combined a comprehensive history of opium with a clear-eyed look at today's opioid crisis. By unpacking the complex story of how this powerful drug has woven its way through human history and cultures, they give readers profound insight into what drives contemporary use of opium and its derivatives as well as realistic, effective, and compassionate recommendations for helping those who suffer from the disease of addiction."Dr. Andrew Weil (MD)

-

"An engrossing and highly readable account of our tangled relationship with a flower."Sam Quinones, authorof Dreamland: The True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic

-

"A fascinating account from a psychiatrist who is also an expert in addiction medicine."Lit Hub

-

"Halpern and Blistein take us on an astonishing journey through time and space, revealing how racism and ethnic prejudice have distorted popular views of opium for centuries and how those who were at one time said to be paragons of American virtue-from Harry Anslinger to Joseph McCarthy to the Sackler family -- have played their part in creating the opiate epidemic. With Opium, we can more fully understand how and why the 'war on drugs' keeps failing. A fascinating read with practical advice on how to get out of the mess we're in."Julie Holland, MD, NewYork Times bestselling author of Weekends at Bellevue and MoodyBitches

-

"Opium has been entwined with society for millennia. Here, psychiatrist John Halpern and writer David Blistein trace its path from Mesopotamia through ancient Egypt, Greece and Persia, finally reaching Britain and the United States... It is time [for us] to treat addiction as a curable illness -- and learn the lessons of history."Nature, Science Picks of the Week

-

"Opium is the most important, provocative, and challenging book I've read in a long time....Makes timely and startling connections among painkillers, politics, finance, and society in clear, non-technical prose that kept me alternately riveted and amazed. We may not be able to get this drug out of our system, but Opium will help everyone gain a better understanding of and more control over its uses and abuses."Laurence Bergreen, New York Times bestselling author of Marco Polo: From Venice to Xanadu and Over the Edge of the World: Magellan's Terrifying Circumnavigation ofthe Globe

-

"Authoritative, engaging, and accessible, this call for action offers solutions -- insurance and criminal justice reforms, alternative treatments, and eradication of punishment -- and avenues to greater overall understanding."Booklist

-

"Detailed and highly readable...[Opium] demonstrates convincingly that the best way to address today's epidemic is to acknowledge addiction as the brain disease that it is...The recommendations in this book should be seriously considered by anyone concerned with today's opioid epidemic."Congressman Patrick J. Kennedy, member of the President's Commission on CombattingDrug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis

-

"Weave[s] together a history of the flower's medicinal uses, the origins of the opium trade and drug wars, and the modern opioid crisis....peppered with colorful anecdotes."Scientific American, Editors' Pick

-

"Highly informed and wonderfully entertaining."Ethan A. Nadelmann, founder of the Drug PolicyAlliance

-

"Halpern and Blistein expertly weave together the many strands of opium's history, from the poppy growers of Neolithic times to the politics of today's opiate epidemic. By learning the whole story and discovering the many erroneous beliefs and misguided policies that have occurred along the way -- the reader emerges with a far clearer picture of the problem and what perhaps we can do about it now."Harrison G. Pope Jr., MD, professor ofPsychiatry, Harvard Medical School

-

"In this lively, irreverent history we learn what Aristotle and William Burroughs, Helen of Troy and Billie Holiday, El Chapo and Thomas Jefferson had in common. They all either used or prescribed, cultivated or profited from opium. The authors chronicle the quackery the drug has inspired, the colonial wars it caused, and the official follies that led to today's opioid crisis -- and they outline a fresh and sensible approach to ending it."Geoffrey C. Ward, New York Times bestselling author of A First-Class Temperament: The Emergence of Franklin Roosevelt

-

"Thank God (or whatever higher power you desire) that Halpern and Blistein have done the historical work to demystify the use of opioids. Their research now allows us to focus on the issues that really matter, like keeping users safe and ensuring that patients have access to these effective medications."CarlL. Hart, Ph.D., professor of Psychology, Columbia University and author of High Price

-

"This book takes the reader on a deep journey through the history of opium and how it has shaped medicine, culture, trade, and politics....Halpern and Blistein give readers hope that new policies and treatments to alleviate addiction could make a real difference, if politicians and healthcare institutions are willing to set aside failed strategies that, unfortunately, remain in place."Torsten Passie, MD, Goethe-University's Institute for History and Ethics in Medicine

-

"Dramatic...A compelling if somewhat terrifying read -- a wake-up call as to the scale of the challenge and the endless susceptibility of humans to the poppy's most addictive by-product."Geographical