Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

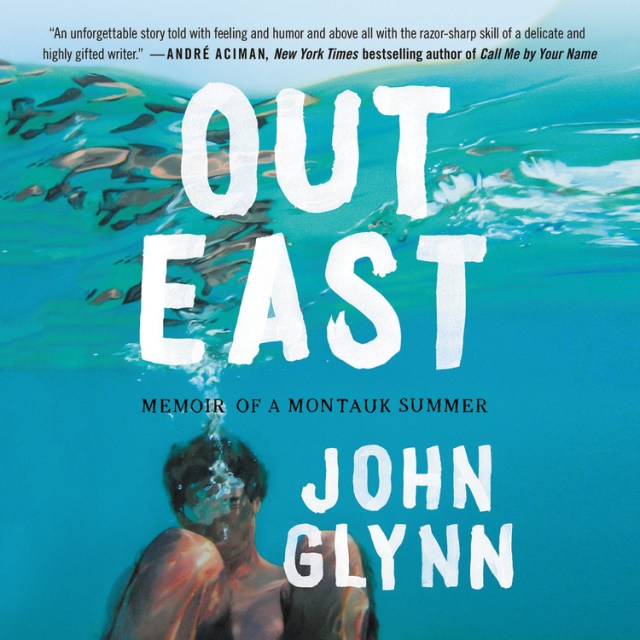

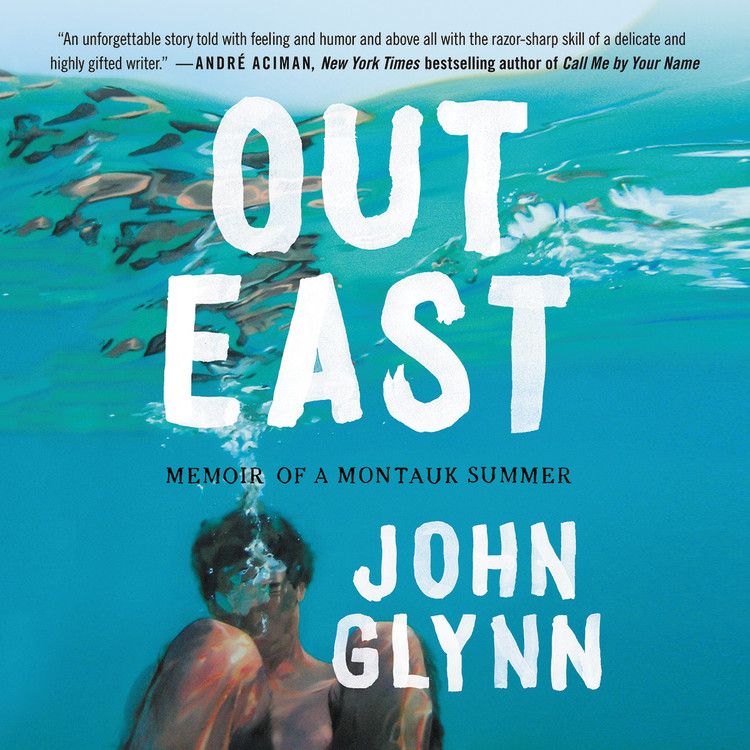

Out East

Memoir of a Montauk Summer

Contributors

By John Glynn

Read by Michael Crouch

Formats and Prices

Format

Format:

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 14, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

An “extraordinary” debut memoir of first love, identity, and self-discovery among a group of friends who became family in a Montauk summer house (Andrew Solomon, National Book Award winner).

They call Montauk the end of the world, a spit of land jutting into the Atlantic. The house was a ramshackle split-level set on a hill, and each summer thirty-one people would sleep between its thin walls and shag carpets. Against the moonlight the house’s octagonal roof resembled a bee’s nest. It was dubbed The Hive.

In 2013, John Glynn joined the share house. Packing his duffel for that first Memorial Day Weekend, he prayed for clarity. At twenty-seven, he was crippled by an all-encompassing loneliness, a feeling he had carried in his heart for as long as he could remember. John didn’t understand the loneliness. He just knew it was there. Like the moon gone dark.

Out East is the portrait of a summer, of The Hive and the people who lived in it, and John’s own reckoning with a half-formed sense of self. From Memorial Day to Labor Day, The Hive was a center of gravity, a port of call, a home. Friendships, conflicts, secrets and epiphanies blossomed within this tightly woven friend group and came to define how they would live out the rest of their twenties and beyond.

Blending the sand-strewn milieu of George Howe Colt’s The Big House with the radiant aching of Olivia Liang’s The Lonely City, Out East is a keenly wrought story of love and transformation, longing and escape in our own contemporary moment.

“An unforgettable story told with feeling and humor and above all with the razor-sharp skill of a delicate and highly gifted writer.” — André Aciman, New York Times bestselling author of Call Me by Your Name

“Out East is full of intimacy and hope and frustration and joy, an extraordinary tale of emotional awakening and lacerating ambivalence, a confession of self-doubt that becomes self-knowledge.” — Andrew Solomon, National Book Award winner

An Entertainment Weekly Best Book of May 2019

A Time magazine Best Book of May 2019

Cosmopolitan Best Book of May 2019

An O, the Oprah Magazine Best LGBTQ Book of 2019

Genre:

-

"Glynn is such a warm, elegant, and gorgeously precise writer...Like the best coming-of-age books, "Out East" is a tender, patient how-to manual, sketching a path to self-actualization, or at least to self-acceptance."The New Yorker

-

"Glynn's memoir is perfectly evocative of long, lazy summers, taking place over a few months in Montauk and charting the blossoming of friendships, the heat of new romances, and the journeys to self-discovery."Entertainment Weekly

-

"A moving account of the particular sort of loneliness that descends when you know you're unhappy but don't quite know why, and the boundless devotion of the chosen family who's there while you're figuring it out."Oprah.com

-

"This book perfectly captures unrequited love and longing, as John struggles with growing feelings for his fellow vacationer... this one is staying on my shelf forever."Cosmopolitan

-

"Sun-soaked and brimming with youth, Glynn's debut memoir chronicles a life-changing summer spent in a Montauk share house. With honesty, heart, and generosity, the memoir explores friendship, first love, and identity."The Millions

-

"'We were sun children chasing an eternal summer.' This boisterous chronicle of a summer in Montauk sees a group of 20-something housemates who'll grow to know, to love, and care for one another. They work hard during the week, party hard on weekends, and each will face heartthrob and heartbreak. A coming out story told with feeling and humor and above all with the razor-sharp skill of a delicate and highly gifted writer."Andre Aciman, New York Times bestselling author of Call Me by Your Name

-

"Out East is full of intimacy and hope and frustration and joy, an extraordinary tale of emotional awakening and lacerating ambivalence, a confession of self-doubt that becomes self-knowledge. It beautifully charts the dynamics of a group of people in a house share, but it's also about the emergence of its narrator into an exquisite emotional honesty. It's gripping and generous, and hidden in its rollicking naivete is a good measure of authentic wisdom."Andrew Solomon, National Book Award winner

-

"Out East personifies summer magic. [It] refashions the epic summer tale, dosed with lyrical brawn, grace, and ingenuity. Summer or not, sharing a cool pop with John Glynn's remarkable Out East will nudge you to believe in believing once again."Lambda Literary

-

"Written with the same clarity and ebullience as E.B. White's 'Once More to the Lake,' if said essay were also infused with equal parts vodka, millennial angst, and sexual longing."Chicago Review of Books

-

"No author has captured a millennial milieu better or with more empathy than John Glynn. Out East is a perfectly paced memoir and riveting portrait of a friend group. I loved it."Anita Shreve, New York Times bestselling author of The Pilot's Wife and The Stars are Fire

-

"John Glynn wonderfully captures it all: the bars, the clothes, the music, the breakups, the giddiness and terror of being young in New York, searching for yourself all week, searching for someone else on weekends, in one of the world's most hauntingly beautiful beach towns. If you're in your twenties you'll smile and nod at the joy and pain of Glynn's quest. If you're not in your twenties, he'll make you feel as if you are. A gorgeous debut."J.R. Moehringer, Pulitzer Prize winner and New York Times bestselling author of The Tender Bar

-

"As a microcosmic rendition of a lost summer's drunken rhythms and Glynn's slowly unfolding realization about his own sexuality, the writing resonates with a shimmery tingle."Publisher's Weekly

-

"It's at its most personal that his memoir shines brightest, grasping at the many ways there are to love and be and ultimately reveling in them."Booklist

-

"John Glynn's Out East is a combination travelogue and memoir. He brings the eye of a cultural explorer to the time-honored ritual of summertime house shares by young people from the city in the beach communities of Long Island and while this in and of itself would be plenty to compel a reader's attention, the book does so much more, layering in the story of the author's own sexual awakening amid the dunes and the drinks and the bravura. His voice throughout, as comforting as a distant horizon and as light as a passing cloud, heralds the arrival of a wonderful new talent."Madeleine Blais, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and author of To the New Owners: A Memoir of Martha's Vineyard

-

"Slyly funny and heroically honest, Out East will charm you on every page, even as you ache for its sensitive and searching narrator. With his gorgeous, precise, soulful prose and discerning eye for sociological detail, John Glynn offers a perceptive, youthful, and heartfelt summertime story of love and longing on the hedonistic shores of Long Island that revives the spirit of Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby to speak for our present moment."Stefan Merrill Block, author of The Story of Forgetting

-

"Glynn has a documentarian's eye and a poet's tongue. He describes an idyllic, privileged summer suffused with personal turmoil and millennial malaise with such beautiful precision. This book is a rare glimpse into an elusive feeling, part dreamlike crush, part seismic shift. This is a memoir about his life but it also generously and wisely shifts perspectives to give a fuller portrait of a group of friends in transition."R. Eric Thomas, author of Here For It

-

"In his tender and inspiring coming-of-age debut, John Glynn explores how a single summer of beer pong, sunshine, and friendship showed him it was time to be honest with the world, and with himself."Ada Calhoun, author of St. Marks Is Dead

-

"Prepare to feel overwhelmed with emotion and the need to start a John Glynn fan club."Popsugar.com

-

"Out is a heart-wrenching reminder of the precarious emotional inner life that undulates just beneath the surface, even for people who seem as though they have it all"Bookpage

-

"A heartfelt coming-of-age story and a fond depiction of a tight-knit friend circle."Newsday

-

"An incredible debut memoir"Out Magazine

-

"Out East is a testament to falling in love with love itself, with the frightening prospect of finally being accepted for exactly who you are."Forbes

- On Sale

- May 14, 2019

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549116094

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use