By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

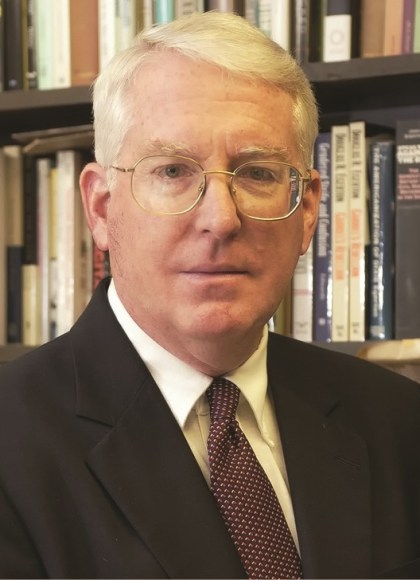

Jefferson

Architect of American Liberty

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Apr 25, 2017

- Page Count

- 640 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465094684

Price

$40.00Price

$50.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- ebook $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 25, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Not since Merrill Peterson’s Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation has a scholar attempted to write a comprehensive biography of the most complex Founding Father. In Jefferson, John B. Boles plumbs every facet of Thomas Jefferson’s life, all while situating him amid the sweeping upheaval of his times. We meet Jefferson the politician and political thinker — as well as Jefferson the architect, scientist, bibliophile, paleontologist, musician, and gourmet. We witness him drafting of the Declaration of Independence, negotiating the Louisiana Purchase, and inventing a politics that emphasized the states over the federal government — a political philosophy that shapes our national life to this day.

Boles offers new insight into Jefferson’s actions and thinking on race. His Jefferson is not a hypocrite, but a tragic figure — a man who could not hold simultaneously to his views on abolition, democracy, and patriarchal responsibility. Yet despite his flaws, Jefferson’s ideas would outlive him and make him into nothing less than the architect of American liberty.

-

"Magisterial...perhaps the finest one-volume biography of an American president."Jonathan Yardley, Washington Post

-

"[A] splendid biography."Wall Street Journal

-

"The fullest and most complete single-volume life of Jefferson since Merrill Peterson's thousand-page biography of 1970."Gordon Wood, Weekly Standard

-

"A sympathetic (though not hagiographic) view of Jefferson that emphasizes the differences between his world and ours....[Jefferson] was, in Mr. Boles's words, the 'architect of American liberty,' a phrase the author uses without the sneers or hedges that have become de rigueur among recent chroniclers of the founding era....[a] splendid biography."Wall Street Journal

-

"[A] good, solid, generally fair-minded biography... [Boles's] biography concentrates on the exterior events of Jefferson's private and public lives and weaves them together in a straightforward, clearly written narrative. It is the fullest and most complete single-volume life of Jefferson since Merrill Peterson's thousand-page biography of 1970."Gordon Wood, Weekly Standard

-

"For all readers interested in understanding the enigmatic and controversial Jefferson as well as his shortcomings and triumphs within the context of his time."Library Journal

-

"In a narrative as majestic as its subject, Boles takes a fresh, nuanced look at one of the America's most enigmatic founding fathers... Boles, an accomplished scholar well versed in the source material, deftly paints a picture of the world as Jefferson knew it, taking care not to mix up understanding with excusing, especially with the Virginian's relationship with Sally Hemings. This is a gem of a biography."Publishers Weekly

-

"John Boles's deeply researched and judiciously balanced Jefferson is an exemplary biography. Animated by a warm and wise admiration for a great American, Boles never loses sight of Jefferson's limitations and failures-or of his extraordinary achievements."Peter Onuf, University of Virginia, and coauthor, with Annette Gordon-Reed, of 'Most Blessed of the Patriarchs': Thomas Jefferson and the Empire of the Imagination

-

"Intensely satisfying... Boles does a particularly skillful job at weaving Jefferson's correspondence and other writings into the busy tempo of his year-to-year life, creating a fascinating dialogue on the page between the reserved and often diffident public man and direct and provocative private writer."Christian Science Monitor

-

"[An] elegant, highly incisive new biography... The detail is impressive, equally so the fluidity of the presentation. The reader is enveloped in Jefferson's world."Booklist

-

"A fully fleshed biography of Thomas Jefferson that emphasizes his creative paradoxes and accomplishments... A stately, knowledgeable study."Kirkus Reviews

-

"John Boles's Jefferson is learned, fluent, sensitive, and magnificently detailed. It gives due attention to the intellectual currents and social circumstances that made Jefferson who he was, and its careful engagement with the complexities of slavery is convincingly integrated into the whole. Professor Boles has earned an eminent place for himself in the ever-active field of Jefferson studies."Andrew Burstein, author of Jefferson's Secrets and coauthor of Madison and Jefferson

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use