By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

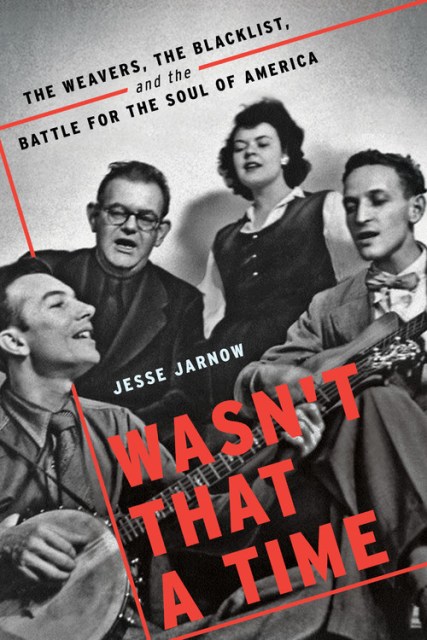

Wasn’t That a Time

The Weavers, the Blacklist, and the Battle for the Soul of America

Contributors

By Jesse Jarnow

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2018

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306902079

Price

$27.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $27.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Following a series of top-ten hits that became instant American standards, the Weavers dissolved at the height of their fame. Wasn’t That a Time: The Weavers, the Blacklist, and the Battle for the Soul of America details the remarkable rise of Pete Seeger’s unlikely band of folk heroes, from basement hootenannies to the top of the charts, and the harassment campaign that brought them down.

Exploring how a pop group’s harmonies might be heard as a threat worthy of decades of investigation by the FBI, Wasn’t That a Time turns the black-and-white 1950s into vivid color, using the Weavers to illuminate a dark and complex period of American history. With origins in the radical folk collective the Almanac Singers and the ambitious People’s Songs, the singing activists in the Weavers set out to change the world with songs as their weapons, pioneering the use of music as a transformative political organizing tool.

Using previously unseen journals and letters, unreleased recordings, once-secret government documents, and other archival research, Jesse Jarnow uncovers the immense hopes, incredible pressures, and daily struggles of the four distinct and often unharmonious personalities at the heart of the Weavers.

In an era defined by a sharp political divide that feels all too familiar, the Weavers became heroes. With a class — and race — conscious global vision that now makes them seem like time travelers from the twenty-first century, the Weavers became a direct influence on a generation of musicians and listeners, teaching the power of eclectic songs and joyous, participatory harmonies.

-

"Wasn't That a Time reads more like a Dickens novel than the history of a folk group. God, what a wild ride. And I remember it well."--Alan Arkin, Academy Award-winning actor and author of An Improvised Life

-

"How many synonyms for 'essential cultural history' are there? In an amnesiac America, nothing's overlooked like our dissident legacies--and nothing's needed more these days. Jarnow's book makes this inoculation into good, gossipy fun, and musically knowledgeable enough that you'll want to reach for the soundtrack and fill in all the blanks."--Jonathan Lethem, author of The Feral Detective and Motherless Brooklyn

-

"The Weavers inspired several generations not only to sing but to try to use music to change the world. Jarnow's deep exploration of their journey is a timely reminder of their importance both in their time and ours."--Elijah Wald, author of Dylan Goes Electric! and Escaping the Delta

-

"A well-researched music biography best read with some traditional American folk songs playing in the background."Kirkus Reviews

-

"[A] dramatic, raucous account...Detailed and smartly reported, this work marvelously captures the four voices in a complex era that influenced pop-folk bands that followed."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

-

"Extensively researched, Jarnow's deep and accomplished portrait of these iconic musicians reverberates with a mastery that will appeal to both fans and everyone interested in the history of music."Booklist

-

"Explores...the creative, idiosyncratic, difficult personalities who briefly bottled lightning and subsequently transformed American music from Bob Dylan's output to schoolhouse sing-alongs...For fans of the Weavers and those they influenced, as well as lovers of 20th-century American folk music."Library Journal

-

"Chronicles the rise, fall and resurgence of one of the most influential bands in music history."Music Connection

-

"Wasn't That A Time does an impressive job of pulling together an array of diverse sources, from secret government files to private journals, painting a rich portrait of the strange days that the Weavers helped define...Every page of Wasn't That A Time is filled with revelations, all told with Jarnow's now-signature freewheeling style. A fantastic read."Aquarium Drunkard

-

"An engaging account of the rise, fall, resurrection and legacy of the Weavers...[Jarnow] captures the distinctive personalities and the intertwining voices."New York Times Book Review

-

"Jarnow has a gift for remapping historical terrain you thought you knew every feature of already. This time it's the folk movement of the '40s and '50s and the scourge of McCarthyism he brings vividly to life."CityPages

-

"Jarnow covers the rise, fall and overall legacy of The Weavers in a comprehensive way that no one has done before in print, making this a must-read for any fan of past and/or present folk music."The Hype

-

"An inspiring story of performers dedicated to fighting the good fight, whatever the costs."Record Collector

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use