By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

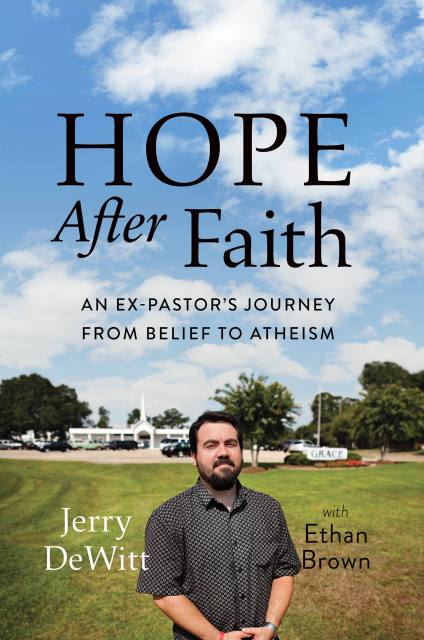

Hope after Faith

An Ex-Pastor's Journey from Belief to Atheism

Contributors

By Jerry DeWitt

With Ethan Brown

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 25, 2013

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780306822506

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 25, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Atheism's leading lights have long been intellectuals raised in the secular and academic worlds: Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and the late Christopher Hitchens. By contrast, Jerry DeWitt was born and bred into the church and was in fact a Pentecostal preacher before arriving at atheism through an extraordinary dialogue with faith that spanned more than a quarter of a century. Hope After Faith is his account of that journey.

DeWitt was a pastor in the town of DeRidder, Louisiana, and was a fixture of the community. In private, however, he'd begun to question his faith. Late one night in May 2011, a member of his flock called seeking prayer for her brother who had been in a serious accident. As DeWitt searched for the right words to console her, speech failed him, and he found that the faith which once had formed the cornerstone of his life had finally crumbled to dust. When it became public knowledge that DeWitt was now an atheist, he found himself shunned by much of DeRidder's highly religious community, losing nearly everything he'd known.

DeWitt's struggle for identity and meaning mirrors the one currently facing millions of people around the world. With both agnosticism and atheism entering the mainstream—one in five Americans now claim no religious affiliation, according to a recent study—the moment has arrived for a new atheist voice, one that is respectful of faith and religious traditions yet warmly embraces a life free of religion, finding not skepticism and cold doubt but rather profound meaning and hope. Hope After Faith is the story of one man's evolution toward a committed and considered atheism, one driven by humanism, a profound moral dimension, and a happiness and self-confidence obtained through living free of fear.

DeWitt was a pastor in the town of DeRidder, Louisiana, and was a fixture of the community. In private, however, he'd begun to question his faith. Late one night in May 2011, a member of his flock called seeking prayer for her brother who had been in a serious accident. As DeWitt searched for the right words to console her, speech failed him, and he found that the faith which once had formed the cornerstone of his life had finally crumbled to dust. When it became public knowledge that DeWitt was now an atheist, he found himself shunned by much of DeRidder's highly religious community, losing nearly everything he'd known.

DeWitt's struggle for identity and meaning mirrors the one currently facing millions of people around the world. With both agnosticism and atheism entering the mainstream—one in five Americans now claim no religious affiliation, according to a recent study—the moment has arrived for a new atheist voice, one that is respectful of faith and religious traditions yet warmly embraces a life free of religion, finding not skepticism and cold doubt but rather profound meaning and hope. Hope After Faith is the story of one man's evolution toward a committed and considered atheism, one driven by humanism, a profound moral dimension, and a happiness and self-confidence obtained through living free of fear.

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use