By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

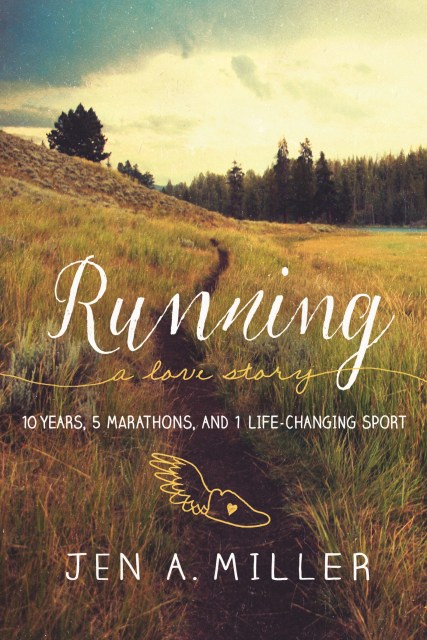

Running: A Love Story

10 Years, 5 Marathons, and 1 Life-Changing Sport

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 22, 2016

- Page Count

- 244 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580056113

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 22, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In Running: A Love Story, Jen tells the story of her lifelong relationship with running, doing so with wit, thoughtfulness, and brutal honesty. Jen first laces up her sneakers in high school, when, like many people, she sees running as a painful part of conditioning for other sports. But when she discovers early in her career as a journalist that it helps her clear her mind, focus her efforts, and achieve new goals, she becomes hooked for good.

Jen, a middle-of-the-pack but tenacious runner, hones her skill while navigating relationships with men that, like a tricky marathon route, have their ups and downs, relying on running to keep her steady in the hard times. As Jen pushes herself toward ever-greater challenges, she finds that running helps her walk away from the wrong men and learn to love herself while revealing focus, discipline, and confidence she didn’t realize she had. Relatable, inspiring, and brutally honest, Running: A Love Story, explores the many ways that distance running carves a path to inner peace and empowerment by charting one woman’s evolution in the sport.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use