Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

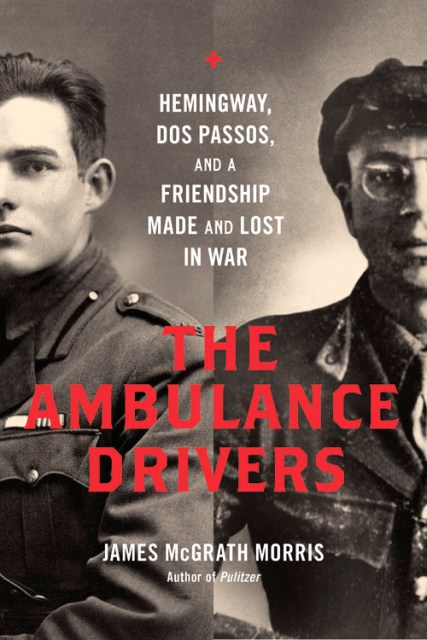

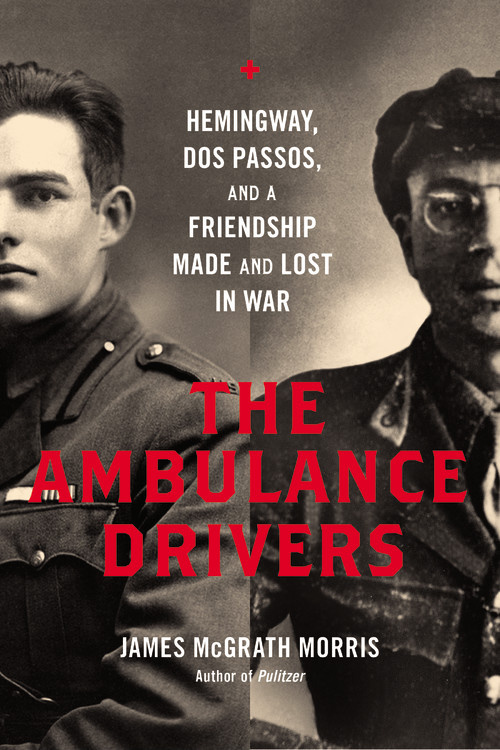

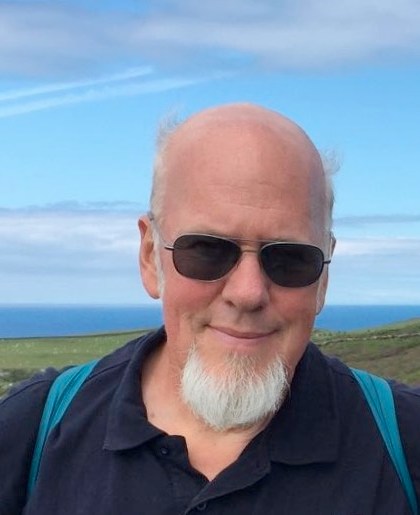

The Ambulance Drivers

Hemingway, Dos Passos, and a Friendship Made and Lost in War

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 28, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Eager to find his way in life and words, John Dos Passos first witnessed the horror of trench warfare in France as a volunteer ambulance driver retrieving the dead and seriously wounded from the front line. Later in the war, he briefly met another young writer, Ernest Hemingway, who was just arriving for his service in the ambulance corps. When the war was over, both men knew they had to write about it; they had to give voice to what they felt about war and life.

Their friendship and collaboration developed through the peace of the 1920s and 1930s, as Hemingway’s novels soared to success while Dos Passos penned the greatest antiwar novel of his generation, Three Soldiers. In war, Hemingway found adventure, women, and a cause. Dos Passos saw only oppression and futility. Their different visions eventually turned their private friendship into a bitter public fight, fueled by money, jealousy, and lust.

Rich in evocative detail — from Paris cafes to the Austrian Alps, from the streets of Pamplona to the waters of Key West — The Ambulance Drivers is a biography of a turbulent friendship between two of the century’s greatest writers, and an illustration of how war both inspires and destroys, unites and divides.

Genre:

-

"The story of the close yet volatile friendship between John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway...[A] lively biography of their relationship...A welcome new look at Dos Passos and another sad chapter in the life of Hemingway."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Two of the most significant writers of their generation, John Dos Passos and Ernest Hemingway, are described by Morris in his evocative, lively volume about how differently they emerged from the crucible of WWI...Morris's narrative demonstrates how, despite jealousies and differences, the two men found common ground...Dos Passos will be the less recognizable name to most readers, and Morris does a great service by reinserting him into the picture of post-WWI American writers."Publishers Weekly

-

"Morris's evocative writing and finely tuned research brings alive the richness of the past--the thronging cafes of Paris, the mortared trenches of Italy, the bullfights of Pamplona, the sun-bleached houses of Key West--as well as the complex personalities of these two great American writers. A tragic story, beautifully written and compulsively readable."--Douglas Preston, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Lost City of the Monkey God

-

"The Ambulance Drivers is one of those rare and gratifying books that seamlessly drops gems of insight on history, art, and politics into a taut and suspenseful story of one of the great literary friendships of the twentieth century."--Debby Applegate, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Most Famous Man in America

-

"Here is a story of war, love, and politics writ large, a story of two literary lions trapped in a double-helix relationship more powerful than either will admit. In this intricately braided dual biography, Morris shows us how the two novelists needed each other, even as they differed--often drastically so--in the way they negotiated the gravitational forces of their times."--Hampton Sides, bestselling author of In the Kingdom of Ice and Ghost Soldiers

-

"In this ingenious dual narrative, James McGrath Morris gives us two lives in high contrast, rendering sharp, revelatory portraits of literary icons we thought we already knew. Writing with deep knowledge and sympathy, Morris has created something rare and fresh: a biography of a friendship."--Megan Marshall, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Margaret Fuller and Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast

-

"Intimate, vivid, and humane, The Ambulance Drivers propels readers through the intersecting lives of two of our greatest writers. Never have Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos seemed so real or so important as in James McGrath Morris's account of their passage through the Great War and the rise of fascism."--T.J. Stiles, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Custer's Trials

-

"Morris writes like an expressionist painter, evoking the essence of Hemingway and Dos Passos's hard-drinking writing life in Paris, Madrid, and Key West. The Ambulance Drivers is a deft and classy literary adventure, infused with wine, beautiful women, and genuine pathos."--Kai Bird, Pulitzer Prize-winning coauthor of American Prometheus

-

"The Ambulance Drivers is an exciting, revealing, important book that evokes a fascinating era. It shows us Hemingway in a new perspective and, equally important, gives Dos Passos the major attention that he indisputably deserves."--David Morrell, New York Times bestselling author of Murder as a Fine Art

-

"[A] highly entertaining biography of a decades-long and often rivalrous literary friendship."Santa Fe New Mexican

-

"A well-researched book made all the more helpful by copious notes and a good bibliography. For Hemingway and Dos Passos fans, this will be a must-read...A compelling examination of an at-times frail, turbulent and broken friendship."Army Ancestry Research blog

-

"Delves head first into the mercurial relationship of these two American literary legends...Throughout this riveting biography Morris expertly narrates the journeys, relationships, and life-changing events that inspired two of the greatest authors of the 20th century...A lively and engaging biography that takes a fresh look at the life of Dos Passos....Although readers may at first hesitate to embark on yet another analysis of Ernest Hemingway, Morris' framing of the context of his fragile and contemptuous relationship with fellow literary giant John Dos Passos creates a worthwhile read. It will most certainly fascinate Dos Passos and Hemingway aficionados, as well as the casual literary biography enthusiast."New York Journal of Books

-

"A superb examination of the bond that helped shape the modern literary movement in America...A fascinating read that will satisfy specialized scholars and general audiences alike with its careful research and highly readable narrative. The book offers more than straight biography of two of the 20th century's most important American authors-it intertwines selections from works they were producing at significant points in their lives...Morris is masterful in his weaving of the Hemingway and Dos Passos timelines...Morris is adept at making the historical record lifelike, giving a palpable sense of the climate in which these modern writers were forged...Thoughtful and engaging...The Ambulance Drivers will do for Hemingway criticism what Scott Donaldson's vigorous Hemingway and Fitzgerald: The Rise and Fall of a Literary Friendship did in 1999: offer a complete post-mortem analysis of a critically important friendship that had a part in shaping a literary movement."Washington Independent Review of Books

-

"The story of Hemingway and Dos Passos is as exciting as any of their novels...A quick-paced narrative that weaves back and forth between the two men's lives...A riveting and rollicking good read...Sanitizing any dry academic influences, [McGrath Morris] pares his subjects down to an essence that makes them seem real...The book is hard to put down, and leaves us feeling closer to these two remarkable men...There's no doubting that the lives of this generation of writers forms every bit as important a part of their story as the books they produced. The Ambulance Drivers offers a delightful and entertaining entry into that world."Popmatters

-

"Morris tugs the reader into the boozy, bitchy world of his protagonists. Famous friends bustle in and out...As readable as a novel."The Economist

-

"Trim and absorbing."Washington Post

-

"Extremely well-researched, The Ambulance Drivers is the tale of two American writers whose work was affected heavily by the angels and demons of a lost generation that conspired to put them at odds."Chico News & Review

-

"Dos Passos gets his due in James McGrath Morris' The Ambulance Drivers...A well-written and interesting book about an interesting time and two very interesting writers."Washington Times

-

"Full of historical and personal details."Dallas Morning News

-

"James McGrath Morris jettisons most of the minutiae necessary in a normal biography and the result reads more like a novel than a biography. The protagonist is a self-effacing writer, John Dos Passos, and the antagonist a demon-ridden artist, Ernest Hemingway. Morris lets the chips fall where they may."Buffalo News

-

"Deftly catches the essence of the duo's mercurial relationship-and the events that led to the destruction of their friendship...[A] multifaceted book."Idaho Statesman

-

"[An] illuminating examination of the relationship between two great American writers."Terry Fallis, Toronto Globe and Mail

-

"James McGrath Morris looks closely at the difficult friendship of Hemingway and Dos Passos."Elaine Showalter, New York Times

-

"A fascinating story of the friendship between literary giants...A great telling of their struggles and of what led to their successes."San Francisco Book Review

-

"The book ostensibly focuses on their work as ambulance drivers, picking up and transporting badly wounded and dead soldiers, but it also presents the following years of their lives: their inspirations, their relationships, their successes, their failures."Curled Up with a Good Book

-

"Unusual and highly necessary...The value of this important new biography is that we are reminded of how much has been lost-for decades-as the Hemingway Industry stayed in overdrive, while the great and good works of John Dos Passos were gradually consigned to oblivion...We have lost a great deal by not paying more attention to the life and work of John Dos Passos. This new book helps us to rectify that error...Hemingway will always be important. But the most important thing about this new biography is that it reminds us that reading John Dos Passos is even more essential."Neworld Review

-

"Relates in impressive detail the friendship and falling out between two idealistic men whose lives were changed and careers launched while in the trenches."EMS World

-

"Compelling and insightful...Morris's extensive research on his two subjects is evident...While it's easy for some biographies to be bogged down in details and facts, The Ambulance Drivers is a fluid, engrossing read."Portland Book Review

-

"With a clear, direct narrative...James McGrath Morris offers insight into what brought these writers together and what tore them apart. An eye for telling detail makes the postwar world come alive for readers...[Morris] brings these writers to life."New Mexico Magazine

-

Choice

"[Morris] does a good job of identifying the differences in the two men's novel-writing styles and in the audiences they cultivated...One comes away from this book wanting to read or reread Dos Passos...Recommended."

-

"Morris provides a unique perspective by narrating the two authors' life experiences in a way that all veterans can relate to after returning home with the scars of war...This book is a must for anyone with interest in the early portions of the 1900s and how the 'Great World' and the 'war to end all wars' shaped the world we live in today. Morris does an outstanding job of relating the real-life experiences of the two main characters throughout the book to lay the ground work for further investigation of Hemingway's and Dos Passos's written works."Military Review

-

"[An] unknown story about two great American authors...Absorbing...James McGrath Morris brings us a new saga in the ever-fascinating world of Ernest Hemingway."Berkshire Eagle

-

"James McGrath Morris is to be commended for doing something unusual and highly necessary in his book...Rather than merely recycle aspects or elements of the all-too-familiar Hemingway legend, what Morris has done is focus with superlative intent on recapitulating how the First World War galvanized the coming-of-age of young Hemingway."HoneySuckle Magazine

- On Sale

- Mar 28, 2017

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Press

- ISBN-13

- 9780306823831

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use