By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

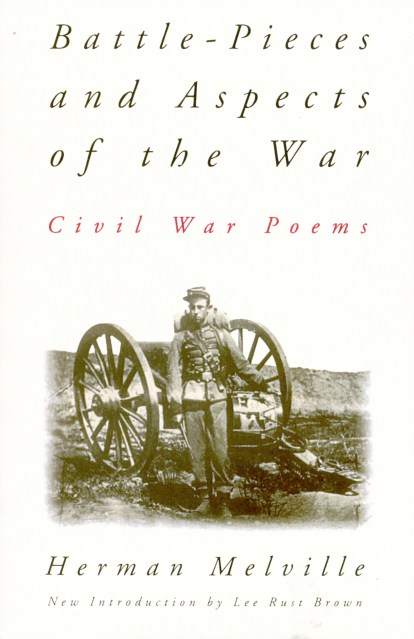

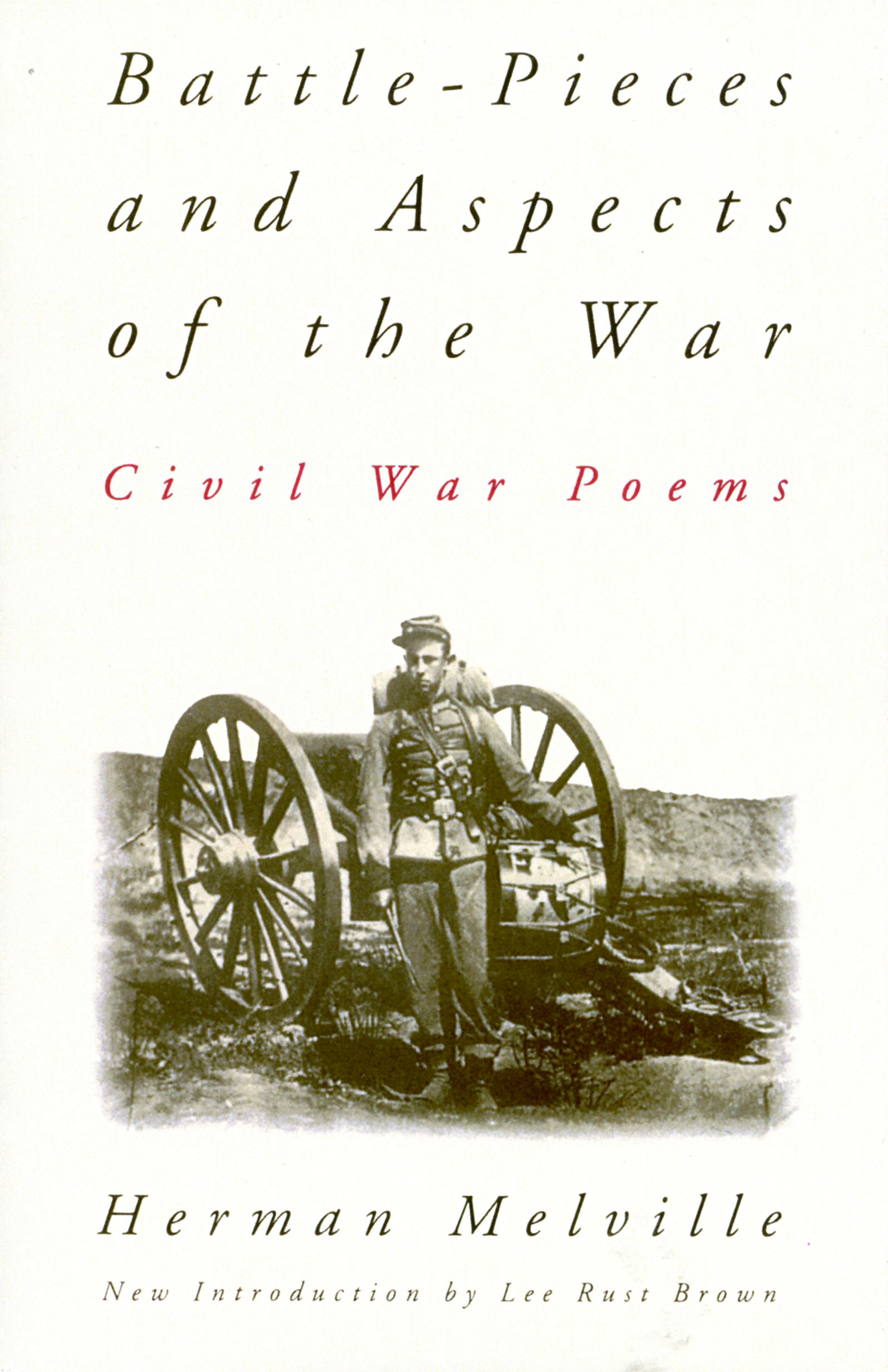

Battle-pieces And Aspects Of The War

Civil War Poems

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 22, 1995

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo

- ISBN-13

- 9780306806551

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 22, 1995. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“A brilliant, magisterial verse opus . . . a masterpiece with virtually no readers.”–Civil War Times

Herman Melville (1819-1891) stopped writing fiction after the publication of The Confidence Man: His Masquerade in 1857; as he entered his forties, he turned to poetry as his literary avocation. His first published book of poems was Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866), a meditation on the Civil War in short lyric and narrative verses, and a work as ambitious and rich as any that issued from his pen.

Melville was well acquainted with the war. He made many trips south to visit his cousin Henry Gansevoort, a Union officer–on one such trip, he was active in an unsuccessful pursuit of Confederate raider John Mosby. He had met Abraham Lincoln in Washington, and called upon General Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia in 1864. And his position within his family, whose members were involved in almost every aspect of the war, was close enough to allow him a rare vantage point on this country’s greatest conflict.

But, Battle-Pieces is anything but epic. Rather than celebratory, the tone of Melville’s poem is grievous and disconsolate. “Unmindful, without purposing to be, of consistency” (as Melville puts it in his preface), the poems do not attempt to paint a broad picture of the whole of the war, but rather represent disjoint aspects, each faithful to Melville’s impulsive, modern, yet realist view of the tragedy.

This facsimile edition of Battle-Pieces includes 72 poems on almost every major campaign, battle, and event; Melville’s own detailed historical notes and his supplementary essay on Reconstruction; and a new introduction by Lee Rust Brown, who teaches English at the University of Utah and is the author of The Emerson Museum. An American classic is thus available once again.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use