By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

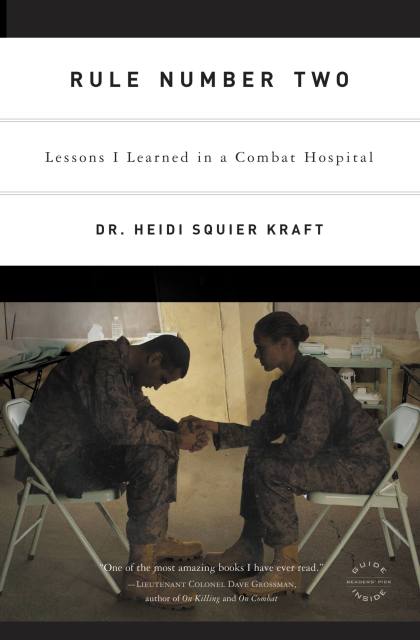

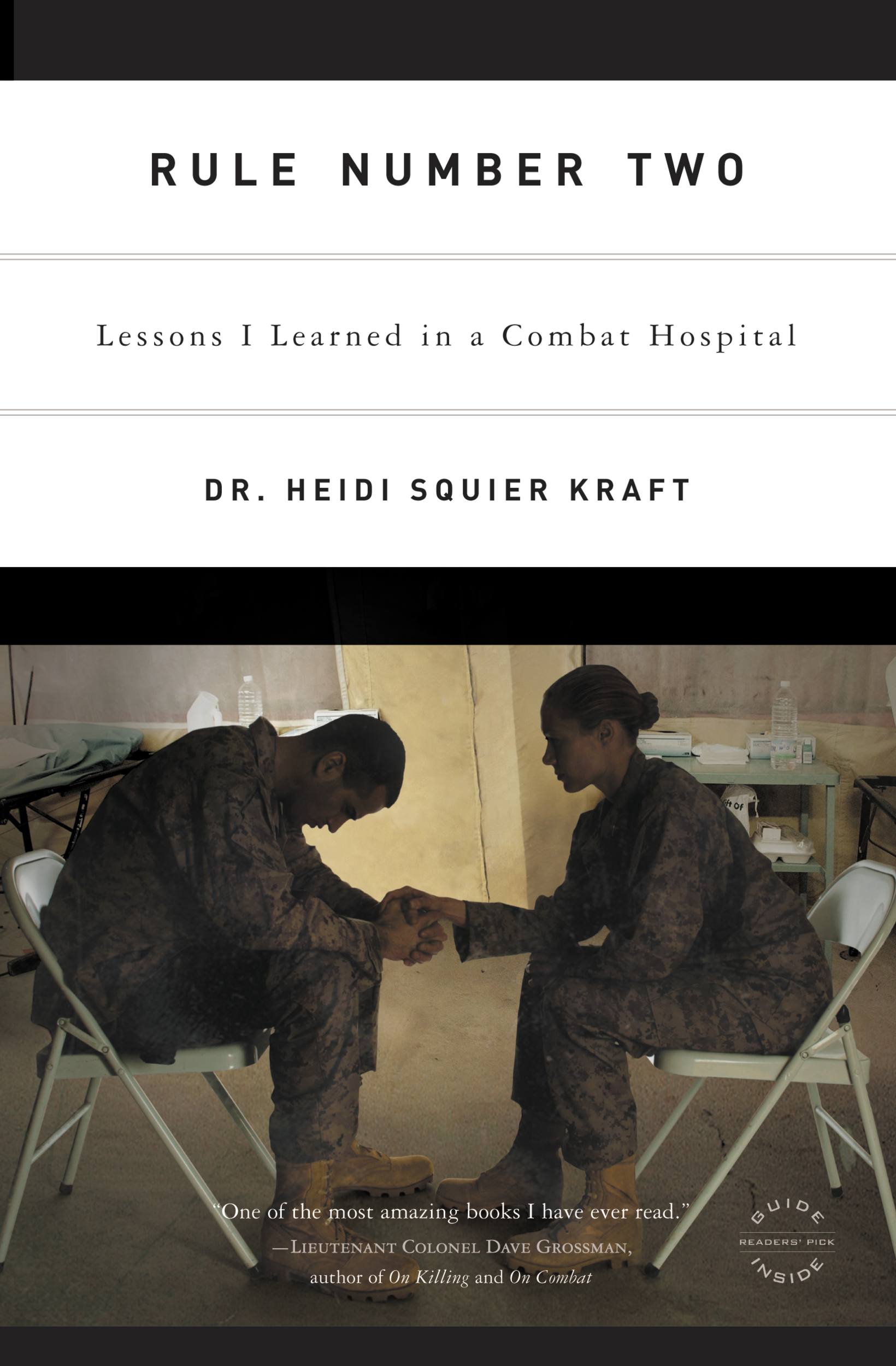

Rule Number Two

Lessons I Learned in a Combat Hospital

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 24, 2007

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316022972

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $10.99 $13.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 24, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

When Lieutenant Commander Heidi Kraft’s twin son and daughter were fifteen months old, she was deployed to Iraq. A clinical psychologist in the US Navy, Kraft’s job was to uncover the wounds of war that a surgeon would never see. She put away thoughts of her children back home, acclimated to the sound of incoming rockets, and learned how to listen to the most traumatic stories a war zone has to offer.

One of the toughest lessons of her deployment was perfectly articulated by the TV show M*A*S*H: “There are two rules of war. Rule number one is that young men die. Rule number two is that doctors can’t change rule number one.” Some Marines, Kraft realized, and even some of their doctors, would be damaged by war in ways she could not repair. And sometimes, people were repaired in ways she never expected.

Rule Number Two is a powerful firsthand account of providing comfort admidst the chaos of war, and of what it takes to endure.

One of the toughest lessons of her deployment was perfectly articulated by the TV show M*A*S*H: “There are two rules of war. Rule number one is that young men die. Rule number two is that doctors can’t change rule number one.” Some Marines, Kraft realized, and even some of their doctors, would be damaged by war in ways she could not repair. And sometimes, people were repaired in ways she never expected.

Rule Number Two is a powerful firsthand account of providing comfort admidst the chaos of war, and of what it takes to endure.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use