Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

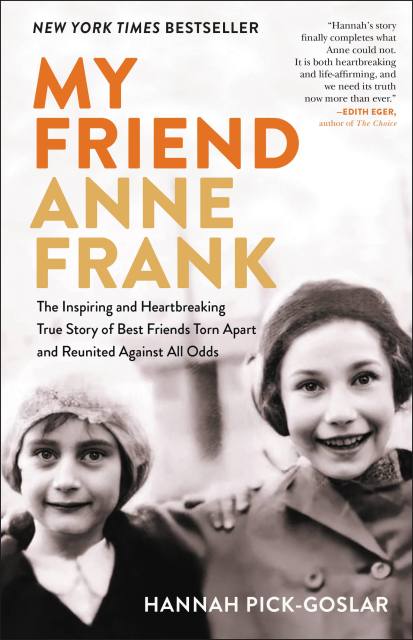

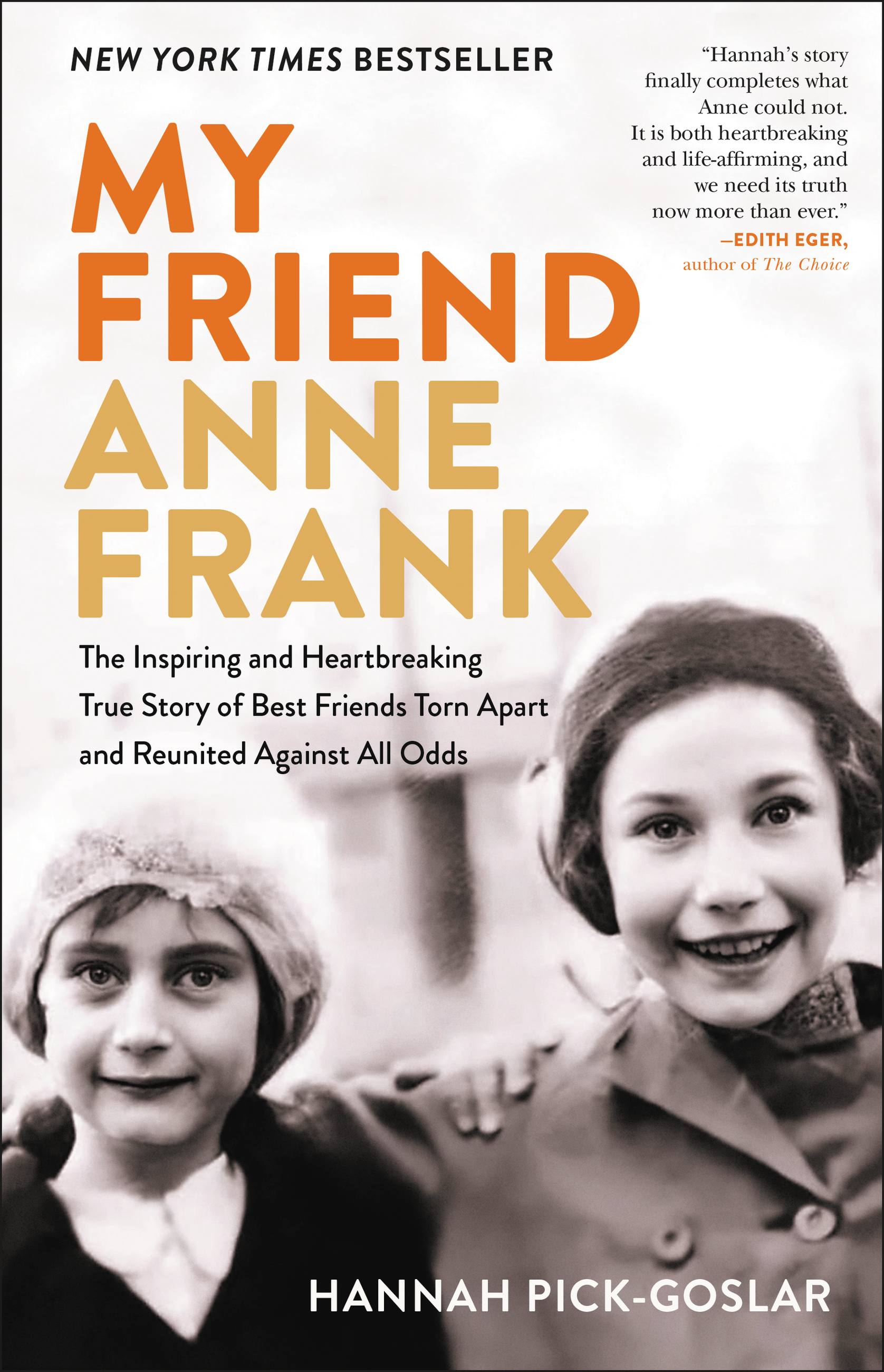

My Friend Anne Frank

The Inspiring and Heartbreaking True Story of Best Friends Torn Apart and Reunited Against All Odds

Contributors

With Dina Kraft

Formats and Prices

Price

$29.00Price

$37.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 6, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In 1933, Hannah Pick-Goslar and her family fled Nazi Germany to live in Amsterdam, where she struck up a close friendship with her next-door neighbor, an outspoken and fun-loving young girl named Anne Frank. For several years, the inseparable pair enjoyed a carefree childhood of games, sleepovers, and treats with the other children in their neighborhood of Rivierenbuurt. But in 1942, Hannah and Anne's lives abruptly changed forever. As the Nazi occupation of Amsterdam progressed, Anne and the Frank family seemingly vanished, leaving behind unmade beds and dishes in the sink—but no trace of Anne's precious diary. Torn from her dear friend without warning, Hannah spent the next two years tormented by questions about Anne's fate, wondering if she had, by some miracle, managed to escape danger.

In this long‑awaited memoir, Hannah shares the story of her childhood during the Holocaust, from the introduction of anti-Jewish laws in Amsterdam to the gradual disappearance of classmates and, eventually, the Frank family, to Hannah and her family's imprisonment in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. As Hannah chronicles the experiences of her own life during and after the war, she provides a searing look at what countless children endured at the hands of the Nazi regime, as well as an intimate, never‑before‑seen portrait of the most recognizable victim of the Holocaust. Culminating in an astonishing fateful reunion, My Friend Anne Frank is the profoundly moving story of childhood and friendship during one of the darkest periods in the world's history.

Genre:

-

“Hannah’s story finally completes what Anne could not. It is both heartbreaking and life-affirming, and we need its truth now more than ever.”Edith Eger, author of The Choice

-

“An extraordinary story of love, loss, and the power of friendship in the darkest time. This book, like its author, is an essential companion to Anne Frank’s life.”Jack Fairweather, Costa Prize-winning author of The Volunteer

-

"A profoundly moving account…an immensely valuable contribution not just to our knowledge of Anne Frank, but to the memory of the Holocaust itself."Dave Rich, author of Everyday Hate

-

“One of the most moving, profound, and important books I've ever read.”Rangan Chatterjee, host of the podcast Feel Better, Live More

-

“A heartbreaking memoir of friendship, loss and survival. By telling her life story, Hannah Goslar pays tribute to her best friend Anne Frank and the millions of others who did not survive the Holocaust. But she also shows us how to preserve our humanity in the face of evil.”Ronald Leopold, executive director of the Anne Frank House

-

“Every bit as remarkable as the Anne Frank story. Hannah has left us a jewel.”Jon Sopel

-

“Pick-Goslar certainly has a story, and she tells it here with great clarity and conviction. In many ways her experience parallels Anne Frank’s.”Francine Prose, The Washington Post

-

“Hannah Pick-Goslar details the joys of their friendship and harrowing details of life under Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime…A devastating account of the Holocaust.”Olivia B. Waxman, TIME

-

“A powerful book.”Tony Dokoupil, CBS Mornings

-

“Painful history but a good choice for readers interested in Anne Frank or Holocaust-era memoirs.”Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- Jun 6, 2023

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316564403

Hannah and Anne Frank in their classroom at the 6th Montessori school

in Amsterdam, 1938. Hannah is on the far left, seated towards the back,

and Anne stands in a white pinafore to the left of their teacher.

Source: Anne Frank House, Amsterdam.

Hannah with her family. From left to right: Hannah’s grandmother Therese Klee;

Hannah; Hannah’s uncle Hans Klee; Hannah’s aunt Eugenie; Hannah’s baby sister,

Gabi, on the lap of her grandfather Hans Klee; Hannah’s mother, Ruth, and

Hannah’s father, Hans Goslar (standing).

Otto and Anne Frank (centre) with other guests at the wedding

of Miep and Jan Gies, 16 July 1941.

Source: Anne Frank House, Amsterdam.

Hannah and Gabi with their aunt Edith after the war, c. 1947.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use