By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

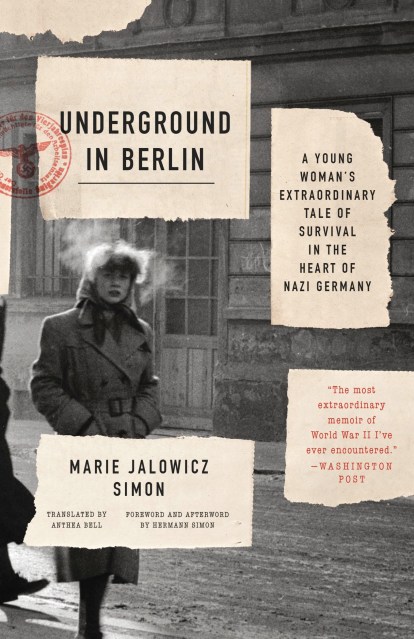

Underground in Berlin

A Young Woman's Extraordinary Tale of Survival in the Heart of Nazi Germany

Contributors

Translated by Anthea Bell

Afterword by Hermann Simon

Foreword by Hermann Simon

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- May 3, 2016

- Page Count

- 384 pages

- Publisher

- Little Brown Spark

- ISBN-13

- 9780316382106

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- Hardcover $40.00

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 3, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In 1942, Marie Jalowicz, a twenty-year-old Jewish Berliner, made the extraordinary decision to do everything in her power to avoid the concentration camps. She removed her yellow star, took on an assumed identity, and disappeared into the city.

In the years that followed, Marie took shelter wherever it was offered, living with the strangest of bedfellows, from circus performers and committed communists to convinced Nazis. As Marie quickly learned, however, compassion and cruelty are very often two sides of the same coin.

Fifty years later, Marie agreed to tell her story for the first time. Told in her own voice with unflinching honesty, Underground in Berlin is a book like no other, of the surreal, sometimes absurd day-to-day life in wartime Berlin. This might be just one woman’s story, but it gives an unparalleled glimpse into what it truly means to be human.

-

A Washington Post Notable Non-Fiction Book of 2015Gerard DeGroot, Washington Post

"The most extraordinary memoir of World War II I've ever encountered." -

"Captivating....Jalowicz's story is unquestionably tragic in so many ways, but is also full of miracles, hope, and a future."Publishers Weekly (Starred review)

-

"Marie Jalowicz Simon transports the reader right to wartime Berlin. Even seventy years later, her voice is young, fresh, and gripping. Her story is by turns funny, wise, and horrific. I felt like she was reaching out to me across time and I couldn't help but fall in love with her. Despite the incredible dangers she faced living underground in Nazi Berlin, Marie's story is incredibly life-affirming and at times, even joyful."Clara Kramer, author of Clara's War

-

"An absolutely gripping account of one young woman's struggle to escape deportation at the hands of the Nazis and of those who helped her. Marie Jalowicz-Simon details for the first time with total honesty the harsh sexual politics of survival in the Berlin underground."Thomas Ertman, New York University, author of Birth of the Leviathan

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use