By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

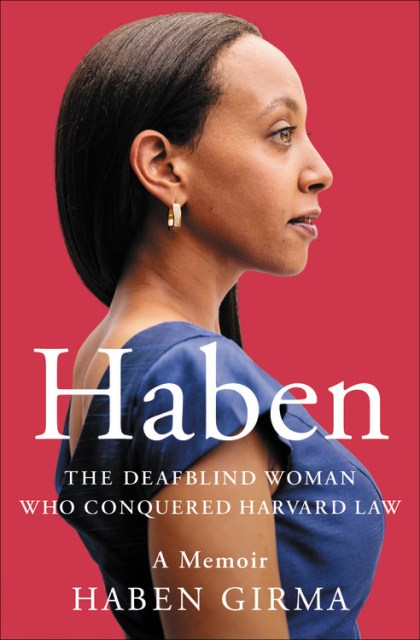

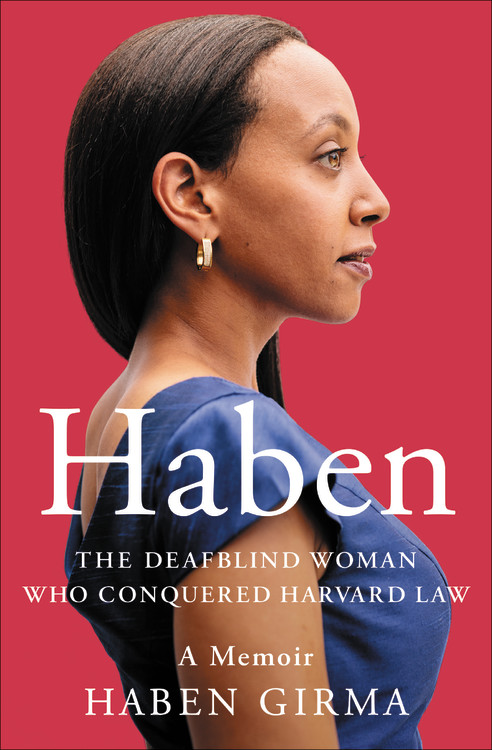

Haben

The Deafblind Woman Who Conquered Harvard Law

Contributors

By Haben Girma

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 11, 2020

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538728734

Price

$19.99Price

$25.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Hardcover $36.00 $47.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 11, 2020. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“This autobiography by a millennial Helen Keller teems with grace and grit.” — O, The Oprah Magazine

“A profoundly important memoir.” — The Times

** As featured in The Wall Street Journal, People, and on The TODAY Show ** A New York Times “New & Noteworthy” Pick ** An O Magazine “Book of the Month” Pick ** A Publishers Weekly Bestseller **

The incredible life story of Haben Girma, the first Deafblind graduate of Harvard Law School, and her amazing journey from isolation to the world stage.

Haben grew up spending summers with her family in the enchanting Eritrean city of Asmara. There, she discovered courage as she faced off against a bull she couldn’t see, and found in herself an abiding strength as she absorbed her parents’ harrowing experiences during Eritrea’s thirty-year war with Ethiopia. Their refugee story inspired her to embark on a quest for knowledge, traveling the world in search of the secret to belonging. She explored numerous fascinating places, including Mali, where she helped build a school under the scorching Saharan sun. Her many adventures over the years range from the hair-raising to the hilarious.

Haben defines disability as an opportunity for innovation. She learned non-visual techniques for everything from dancing salsa to handling an electric saw. She developed a text-to-braille communication system that created an exciting new way to connect with people. Haben pioneered her way through obstacles, graduated from Harvard Law, and now uses her talents to advocate for people with disabilities.

Haben takes readers through a thrilling game of blind hide-and-seek in Louisiana, a treacherous climb up an iceberg in Alaska, and a magical moment with President Obama at The White House. Warm, funny, thoughtful, and uplifting, this captivating memoir is a testament to one woman’s determination to find the keys to connection.

-

"Inspiring."The New York Times

-

"A stirring memoir of love and resilience. Haben proves there are no limits for living joyously in the world. A fierce, glorious advocate for equal opportunity, she demonstrates that accessibility for all benefits all. Her memoir is a soul-inspiring gift."Jewell Parker Rhodes, New York Times bestselling author of Ghost Boys

-

"Reading Haben's story moved me in a way I didn't think was possible. She's a gifted writer, and her story will teach you about strength, perseverance, and determination. This is a strong reminder to embrace the unknown, to stand up for yourself, and to never give up."Mashal Waqar, co-founder and COO, The Tempest

-

"Extraordinary...Haben's is a story of inspiration-and new American patriotism. She gives all of us fresh strength and hope."Lorene Cary, author of Black Ice and founder of Art Sanctuary

-

"What makes Haben's prodigious story even more remarkable is that she's not satisfied with being inspiring. Because she knows that achievement only happens when there is more than the support of individual extraordinary people, she pushes institutions and leaders in the academy, the government, and in big tech to widen the corridors of power and opportunity. Her intersectional approach to her work as an advocate for the disabled and as a Deafblind daughter of refugees refuses tokenization and demands true inclusion."p.p1 {margin: 0.0px 0.0px 9.0px 0.0px; text-align: center; line-height: 11.1px; font: 11.0px Times}dream hampton, award-winning filmmaker, writer, and organizer

-

"Girma...is a talented narrator who captures defining moments in her life in a series of lyrical cameos. She writes with remarkable assurance and yet with a lightness of touch when tackling difficult issues. [A] profoundly important memoir."The Times

-

"Gently powerful...vivid...This really is just the beginning of what is likely to be a long and fascinating story."Forbes

-

"With wit and passion, Haben, a disability rights lawyer, public speaker, and the first Deafblind person to graduate from Harvard Law, takes readers through her often unaccommodating world...This is a heartwarming memoir of a woman who champions access and dignity for all."Publishers Weekly (Starred Review)

-

"This autobiography by a millennial Helen Keller teems with grace and grit."O Magazine

-

"Warmhearted and optimistic, [HABEN] celebrates personal courage and triumph as well as the unlimited potential of those whose real disability is living in a society that too often does not make accommodations for their physical impairments. An inspiring and illuminating memoir."Kirkus

-

"Riveting...[an] often hilarious and utterly inspiring memoir."BookPage (starred review)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use