Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

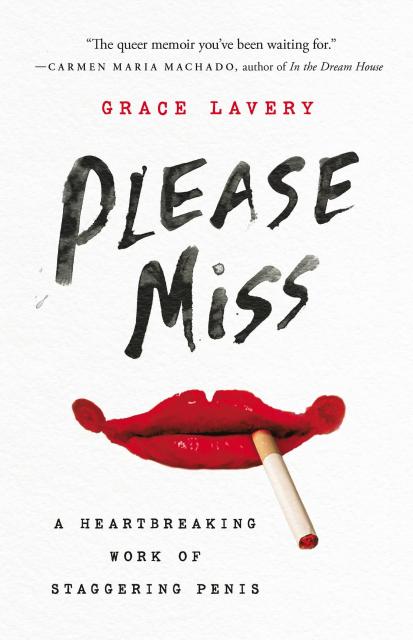

Please Miss

A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Penis

Contributors

By Grace Lavery

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 8, 2022

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781541620643

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $37.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 8, 2022. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

“The queer memoir you’ve been waiting for”—Carmen Maria Machado

Grace Lavery is a reformed druggie, an unreformed omnisexual chaos Muppet, and 100 percent, all-natural, synthetic female hormone monster. As soon as she solves her “penis problem,” she begins receiving anonymous letters, seemingly sent by a cult of sinister clowns, and sets out on a magical mystery tour to find the source of these surreal missives. Misadventures abound: Grace performs in a David Lynch remake of Sunset Boulevard and is reprogrammed as a sixties femmebot; she writes a Juggalo Ghostbusters prequel and a socialist manifesto disguised as a porn parody of a quiz show. Or is it vice versa? As Grace fumbles toward a new trans identity, she tries on dozens of different voices, creating a coat of many colors.

With more dick jokes than a transsexual should be able to pull off, Please Miss gives us what we came for, then slaps us in the face and orders us to come again.

-

“A gleeful middle finger to the expectations of trans memoir… complex, multi-layered, enchanting.”them

-

"With a singular sense of wryness and ribaldry, Lavery charts the course of her gender transition."Tomi Obaro, Buzzfeed

-

“A smart and funny memoir spanning addiction and gender transition, queer theory and standup comedy.”The Guardian, Most Anticipated Books of 2022

-

"Lavery's wild, genre-busting tale of gender transition, addiction and multiple varieties of chaos is both riotously intelligent and dazzlingly hilarious."Evening Standard (London)

-

“Grace Lavery’s unabashed and tantalizing book queers the memoir genre in multiple senses, taking readers on a wild ride through the author’s multitudinous identities.”Electric Lit, Most Anticipated Books of 2022

-

“In this genre-busting work of memoir (or auto-fiction?), Grace Lavery embarks on a myriad of misadventures, including receiving anonymous letters from cultish clowns and starring in a David Lynch remake of Sunset Boulevard.”Autostraddle, Winter preview

-

“Lavery takes a novel approach to the memoir. Melding it with fiction, theory and analysis of popular culture, the result is an untamed beast… weird and wonderful.”Irish Times

-

“Rocking a finely-honed, larger-than-life authorial persona…Lavery’s shattered expectations with an inventive and provocative memoir.”The Herald (Scotland)

-

“Imagine a graduate lit theory seminar interrupted every few minutes by a back-row prankster who has a knack for making the whole room blush. Lavery's ideas float high out of reach at times, but if you grab one, it might just rearrange your thinking around sexuality, freedom, and what it takes to mine joy from this broken world.”The Week

-

“A surreal speculative memoir… Lavery aims to rub out the dividing line between the intellectual and the bawdy. Recounting how she solved her “penis problem” and began taking synthetic estrogen, Lavery explores transcendental erotic self‑realization, her history of drug and alcohol use, and the paradigmatic concept of the penis through absurdist tall tales.”Publisher's Weekly

-

"Never shy at finding the humor in even the most mundane of situations, Lavery hilariously recounts her life as a trans woman in the public eye. Her relationship with fellow writer Danny Lavery comes into focus with her trademark wit and occasional self‑deprecation. The construction and artificiality, the boundaries, the beauty—it’s all here, in Lavery’s body and the bodies of lovers and friends."Library Journal

-

“This is the queer memoir you've been waiting for; a dizzying mix of theory and pastiche, metafiction and memory. Please Miss is Terry Castle meets Lauren Slater meets Michelle Tea; hilarious and sexy and terrifying in its brilliance. But don't worry—Lavery is an avalanche you'll be glad to be buried under.”Carmen Maria Machado, author of In the Dream House and Her Body and Other Parties

-

“Grace Lavery’s Please Miss is a polychromatic, wild and joyous gambol through a world which is like ours but blessedly twisted… Come for the laugh out loud miniature windsock on page one, stay for the fascinating analysis of a discarded pig part in Jude the Obscure, end up profoundly moved and profoundly grateful for this supremely intelligent, innovative, and important tale which is, as Lavery brilliantly puts it, ‘like all the rest, different from all the rest.’”Maggie Nelson, author of The Argonauts

-

“Grace Lavery's memoir – if that's what it is? – is a daring, perverse, mind-blowing, intellectual, hilarious, outrageous, inspired work of art that somehow is touchingly sincere while giving no fucks whatsoever. I read this laughing out loud, clutching my pearls, my mind exploding in wonder. This meditation on trans bodies, queer sex, pop culture, academia, and fantasy rips open bold and badly needed new terrain in literature.”Michelle Tea, author of Against Memoir and Black Wave

-

“Hot, sick, painfully vivid.”Sophie Lewis, author of Full Surrogacy Now

-

“Please Miss is a wickedly smart and filthily funny mosaic of criticism, memoir, and autofiction that is refreshingly avant-garde, profoundly erotic, and as enthralling as an intimate all-night conversation with the brainy high femme BFF you wish you had. I wish it upon everyone.”Melissa Febos, author of Whip Smart and Abandon Me

-

“An unclassifiable pastiche of genuine beauty, a meta-memoir that takes its humor as seriously as its philosophy. Lush, louche, and utterly virtuosic, Please Miss takes a puff off a cigarette, and blooms an astonishing constellation of linked vignettes, an argument given in undercurrent, in root systems, in smoke. Please Miss gives us what we came for and then the much more for which we did not know we could come.”Jordy Rosenberg, author of Confessions of the Fox

-

“In the way that excellent style always blurs the question of genre, Grace Lavery shows how excellent style can blur gender with equal verve. This book reframes the question of transition from the familiar journey from A to B, and replaces that journey with a can’t-look-away performance of wit, language, irreverence, and delight so compelling that a reader forgets about destinations all together.”Torrey Peters, author of Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones and Detransition, Baby

-

“I met Grace when she was still an egg (trans talk for folx who don't know yet that they're trans) and think hers is perhaps the most spectacular, fully formed hatching since Minerva sprang from the head of Zeus.”Susan Stryker, author of Transgender History: The Roots of Today's Revolution, founding editor of Transgender Studies Quarterly, Emmy Award-winning director of Screaming Queens: The Riot at Compton’s Cafeteria

-

“Grace Lavery has somehow managed to blend a rich overview of trans philosophy and theory with a languid, playful sexuality and humor that radiates from every page. It’s a work of great seriousness that doesn’t take itself seriously at all, and as long as I live I will never figure out how she did it.”Nicole Cliffe, author, columnist, editor of The Toast

-

“Please Miss will awe you with its swung prose, its hairpin generic turns, and its bouts of gleeful self-scrutiny. These formal extroversions are part of the book’s argument and a deep insurrectionist pleasure in themselves. One chapter through and you’re ready to draw with Lavery, stand with her, hold with her.”Paul Saint-Amour, Walter H. & Leonore C. Annenberg Professor in the Humanities, University of Pennsylvania

-

“Please Miss cheerfully explodes the trans memoir as political and rhetorical apparatus, refusing norms of uplift or disclosure or cis reader reassurance in favor of the messy magic of a joyfully plural existence. You will annoy loved ones because you’re going to read big chunks of this out loud to them and their jaws will drop at the chutzpah of Grace abounding.”Drew Daniel, of the band Matmos, Associate Professor of English at Johns Hopkins University

-

“Always smart, frequently funny, and sometimes—always tastefully, I assure you—gut-wrenchingly moving, Grace Lavery’s Please Miss is brilliant from start to finish. It’s a howling tale of trans life, addiction, sex, love, loss, and this maddening and delightful meat out of which we are made. Packed as it is with delicious fabulation and sticky detail, the book makes a profound statement about not only what it means to be trans, but also what it means to be meaty, enfleshed, sexed, throbbing with desire, reeling from loss, ragged, loved and pleasured, carved and sutured, and, above all, struggling to find words for any and all of it. What a book! And have I mentioned it’s an absolute delight to read?”Gabriel Rosenberg, Associate Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies at Duke University