Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

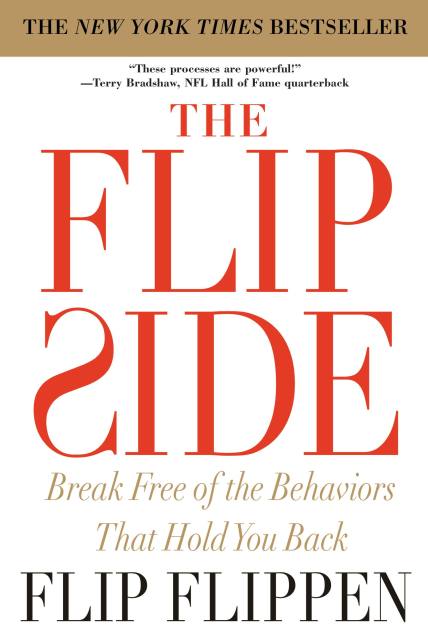

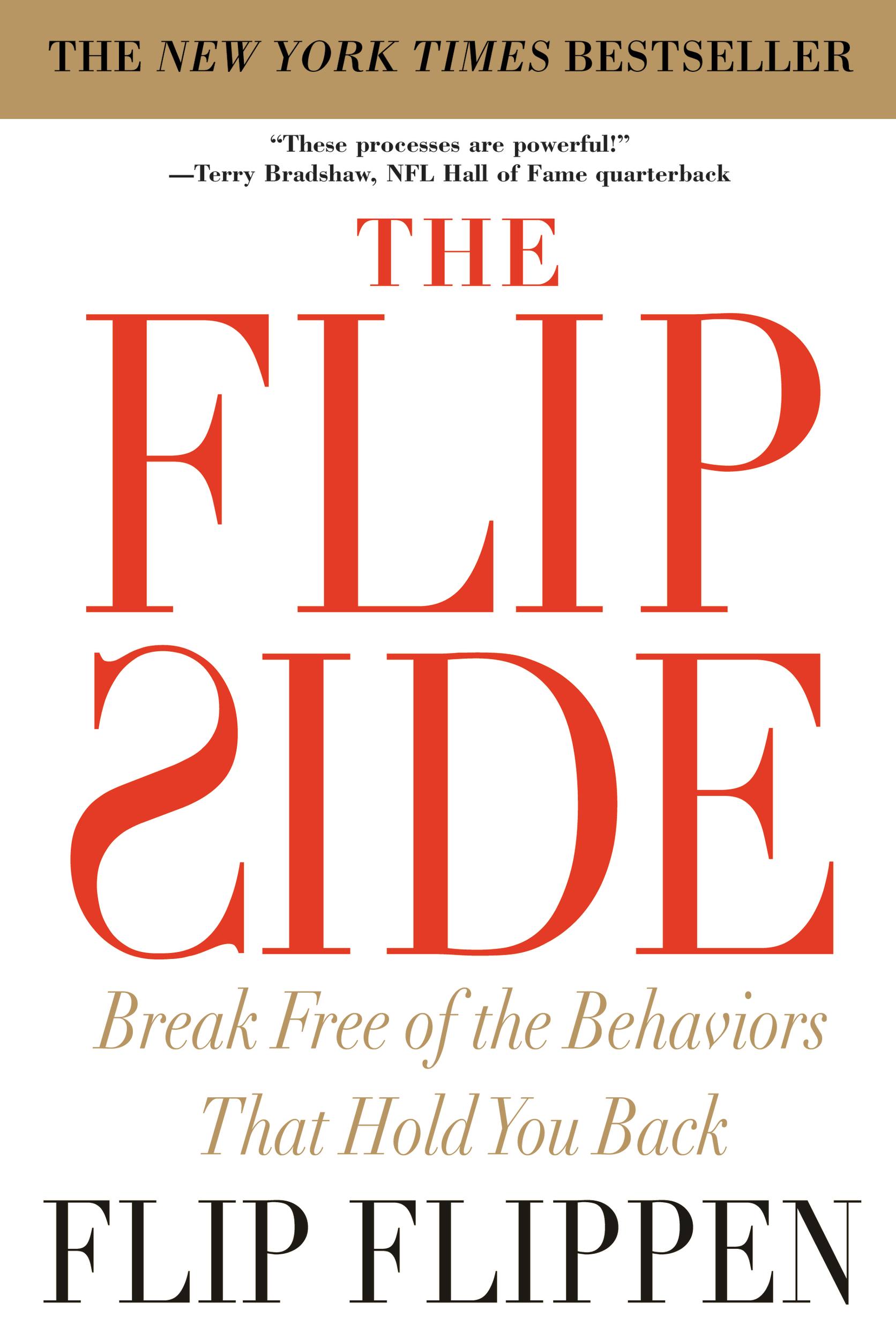

The Flip Side

Break Free of the Behaviors That Hold You Back

Contributors

By Flip Flippen

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 6, 2007

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Balance

- ISBN-13

- 9780446504836

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Abridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 6, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Learn how recognizing your biggest weakness can unleash your greatest strength in THE FLIP SIDE, the bestselling motivational guide by educator, business coach, and growth guru Flip Flippen.

Great advice for everyone, but particularly appealing to those who are taking stock of what they want to do with the rest of their lives, Flippen’s approach is surprisingly simple. When we learn how to identify our “personal constraints” and take the necessary steps to correct self-limiting behaviors, we will experience a dramatic surge in productivity, achieve things we have only dreamed of, and find greater happiness overall. Flippen has created a simple process to help readers find their greatest constraint (the results may be surprising!) and build a plan to help “flip” that weakness into a newfound strength.