By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

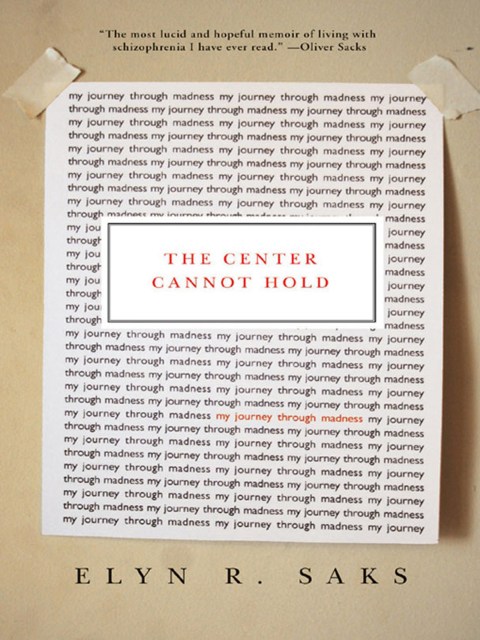

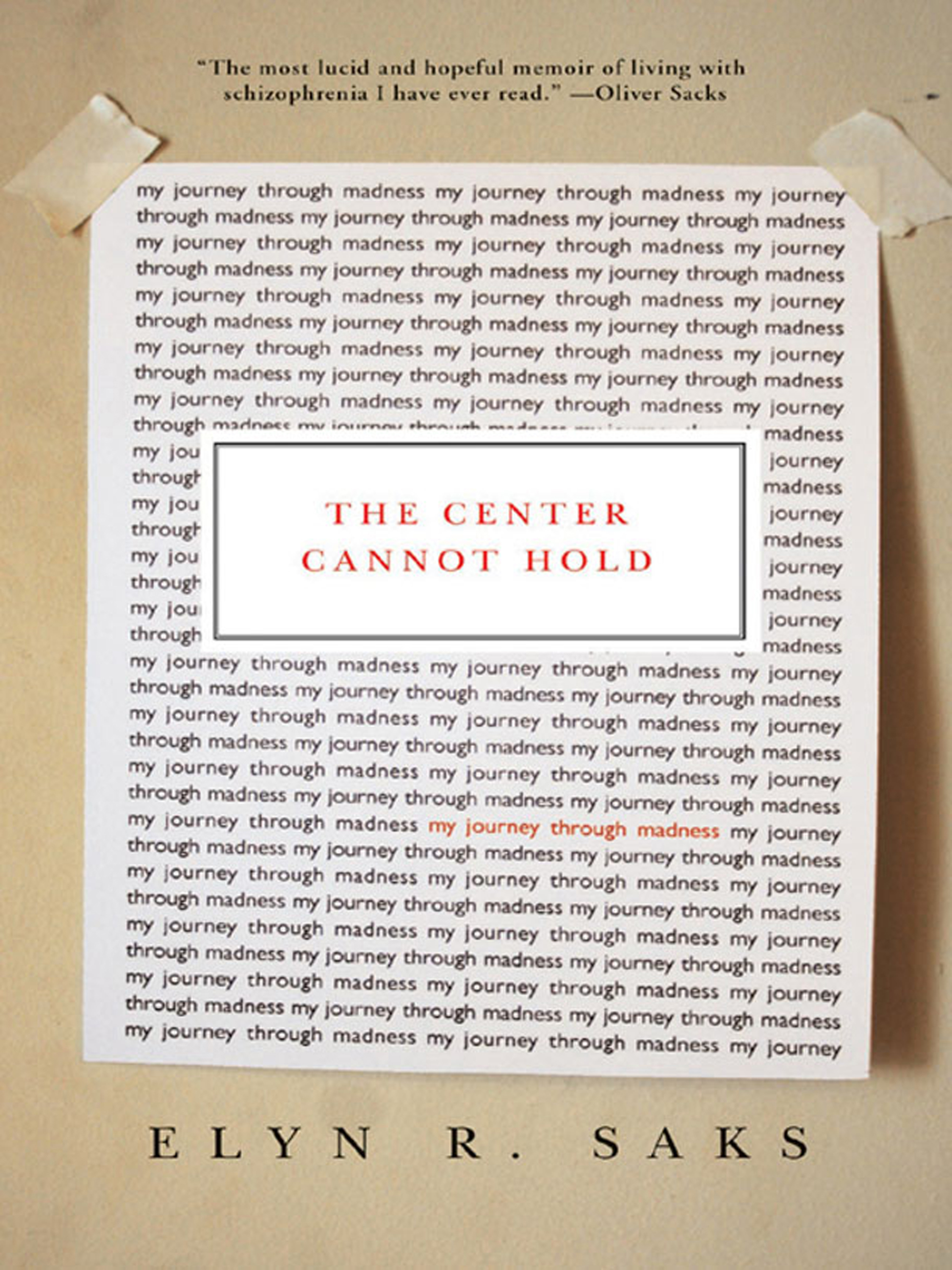

The Center Cannot Hold

My Journey Through Madness

Contributors

By Elyn R. Saks

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 14, 2007

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781401389543

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $39.00 CAD

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 14, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Elyn R. Saks is an esteemed professor, lawyer, and psychiatrist and is the Orrin B. Evans Professor of Law, Psychology, Psychiatry, and the Behavioral Sciences at the University of Southern California Law School, yet she has suffered from schizophrenia for most of her life, and still has ongoing major episodes of the illness.

The Center Cannot Hold is the eloquent, moving story of Elyn’s life, from the first time that she heard voices speaking to her as a young teenager, to attempted suicides in college, through learning to live on her own as an adult in an often terrifying world. Saks discusses frankly the paranoia, the inability to tell imaginary fears from real ones, the voices in her head telling her to kill herself (and to harm others), as well as the incredibly difficult obstacles she overcame to become a highly respected professional. This beautifully written memoir is destined to become a classic in its genre.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use