Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

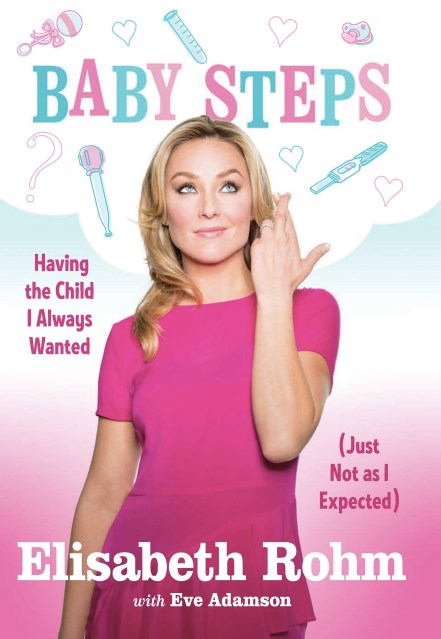

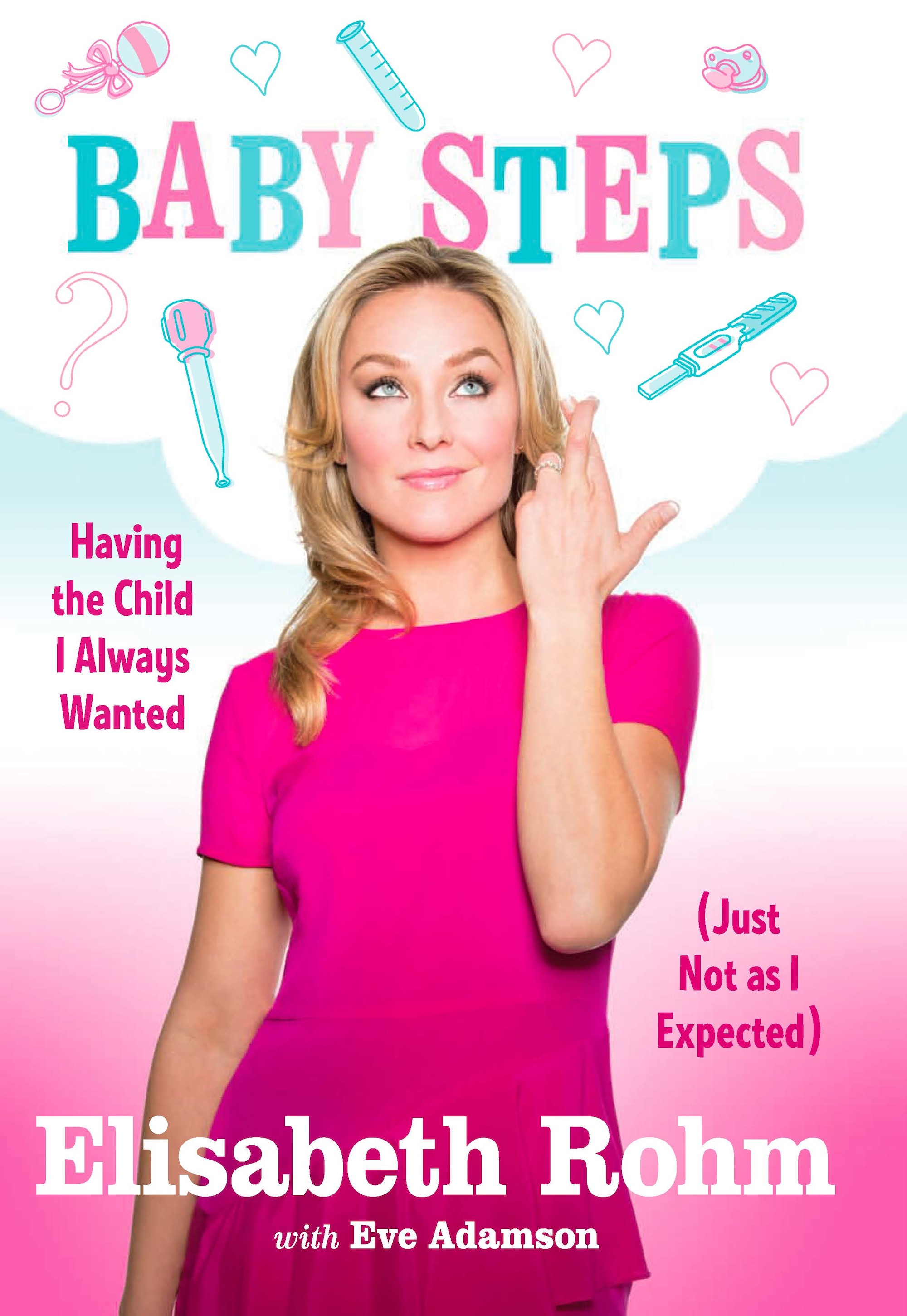

Baby Steps

Having the Child I Always Wanted (Just Not as I Expected)

Contributors

By Eve Adamson

Formats and Prices

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $11.99 $15.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around April 30, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

When Elisabeth Rohm started blogging about her family for People.com, she had no idea how many women would respond to her stories about struggling with infertility. Now the actress best known for her role on Law and Order shares what she hasn’t yet: the full story of how in-vitro fertilization allowed her to have a child, how talking about infertility helped her cope with it, and how her desire for a baby and the difficult path that led to one taught her about herself and made her into the woman she was meant to be.

Rohm’s stories—told in a clear, funny, warmhearted voice—cover her untraditional childhood, and her long journey to motherhood. With the frankness of Down Came the Rain and the hope of A Place of Yes, Röhm encourages all women to share their stories because “when women stop talking, women stop being heard.”

Rohm’s stories—told in a clear, funny, warmhearted voice—cover her untraditional childhood, and her long journey to motherhood. With the frankness of Down Came the Rain and the hope of A Place of Yes, Röhm encourages all women to share their stories because “when women stop talking, women stop being heard.”

Genre:

- On Sale

- Apr 30, 2013

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Da Capo Lifelong Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780738216645

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use