Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

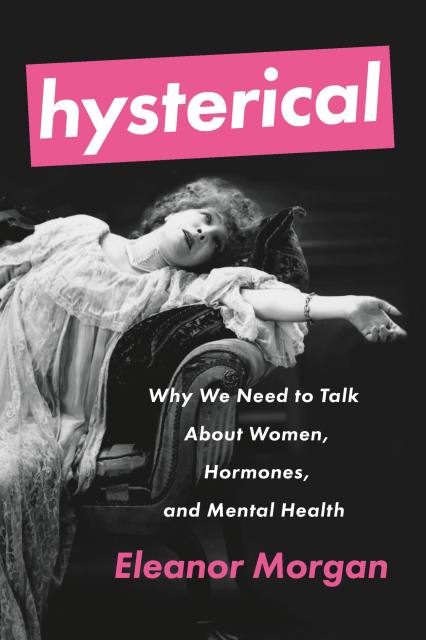

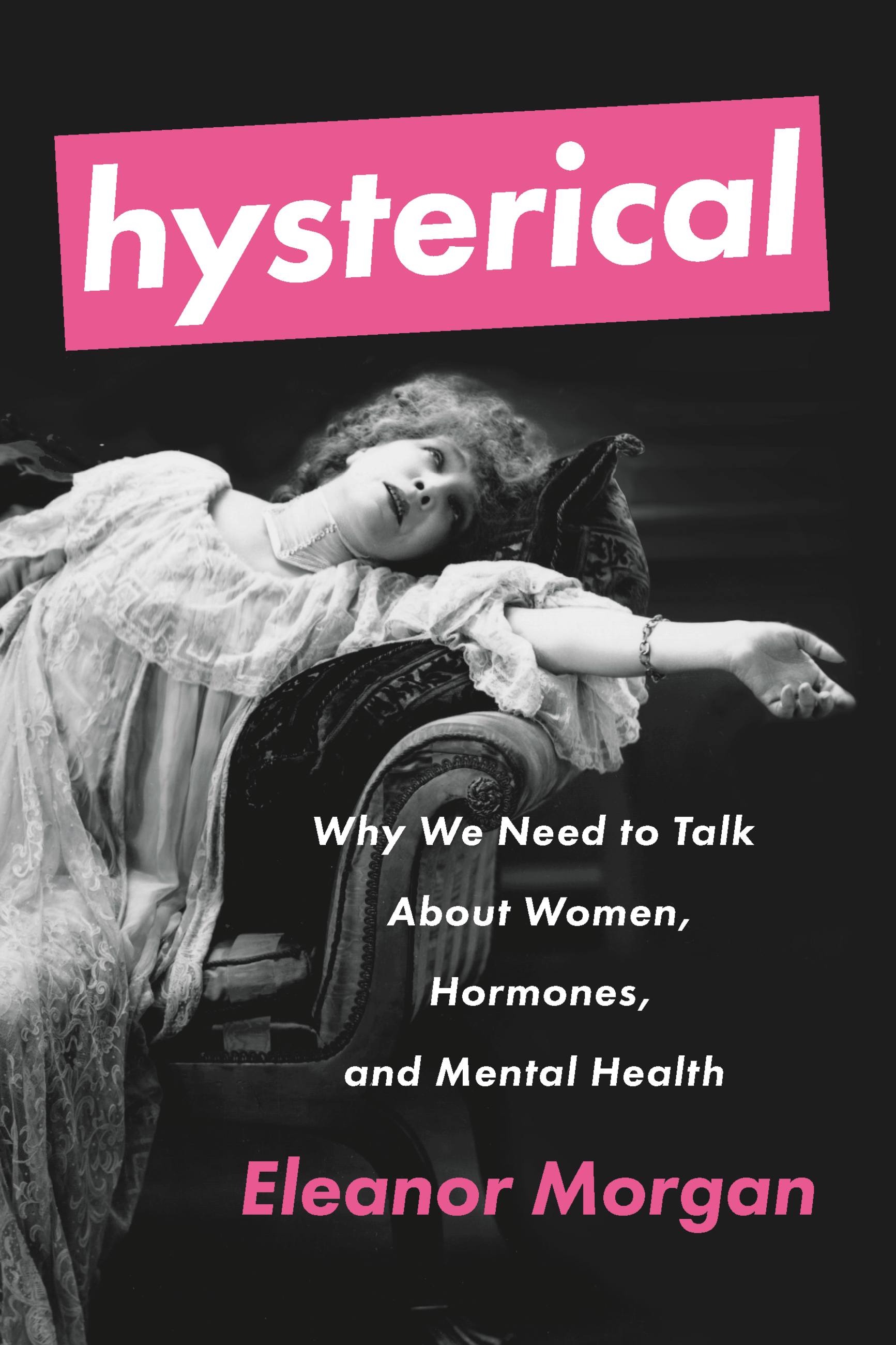

Hysterical

Why We Need to Talk About Women, Hormones, and Mental Health

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Aug 27, 2019

- Page Count

- 288 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580058438

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $18.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 27, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Hysterical seeks to explore the connections between hormones and health, particularly in the frequent mood changes and mental health issues women typically chalk up to the influence of hormones.

Journalist Eleanor Morgan investigates the relationship between biochemistry, our bodies, and our mental health, including the context for this discussion: the historic culture of silence around women’s bodies. As Morgan argues, we’ve gotten better at talking about mental health, but we still shy away from discussing periods, miscarriage, endometriosis, and menopause. That results in a lack of vital understanding for women, particularly as those processes are inextricably connected to our mental health; by exploring women’s bodies in conjunction with our minds, Morgan urges for new thinking about our health.

Examining the mythology of female hormones, the ways that culture shapes our perceptions of women’s bodies, and the latest medical research, Hysterical skillfully paints a portrait of the modern landscape of women and health–and shows us how to navigate stigma and misinformation.