Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

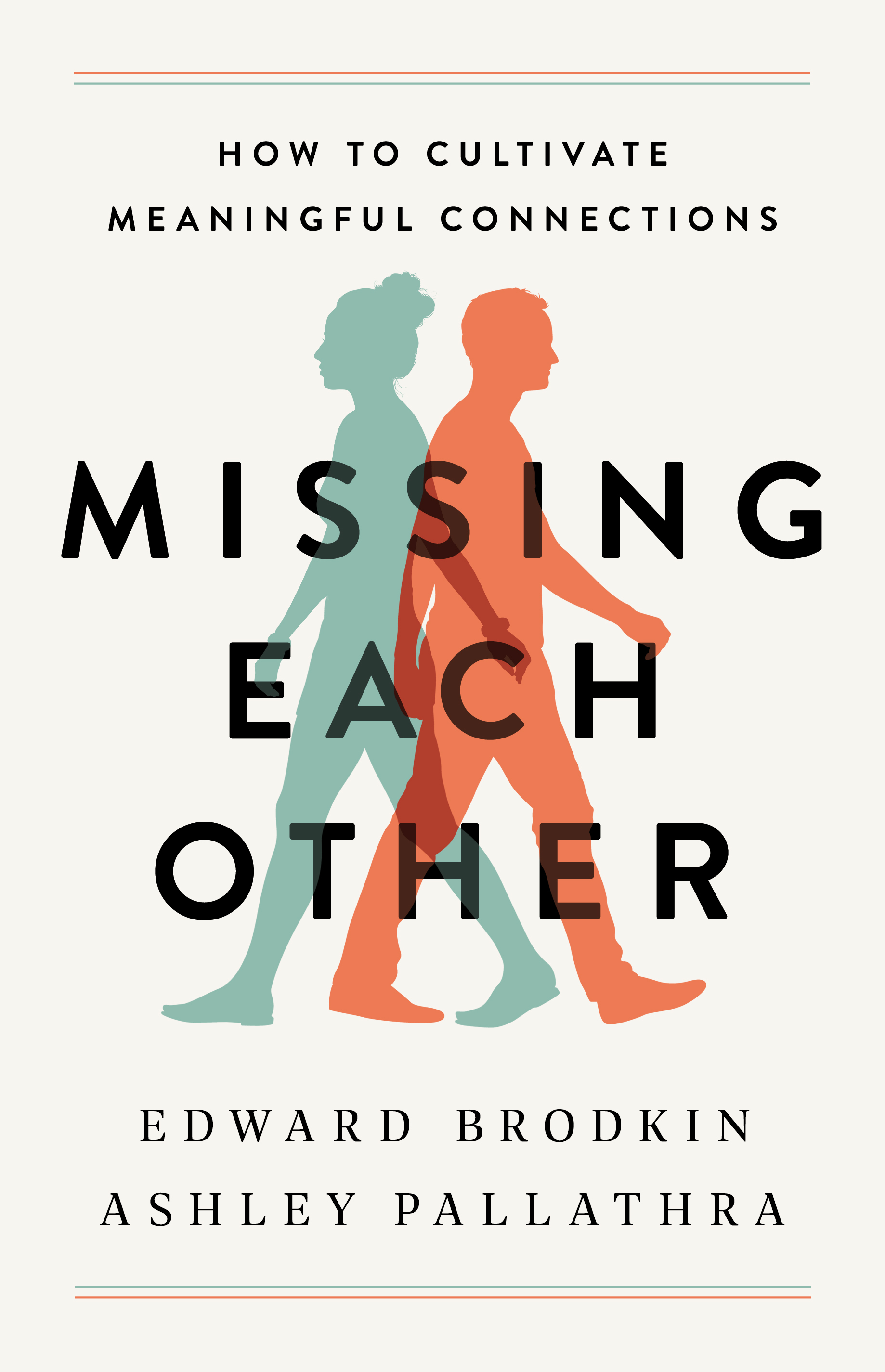

Missing Each Other

How to Cultivate Meaningful Connections

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 26, 2021

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541774018

Price

$28.00Price

$35.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $28.00 $35.00 CAD

- ebook $16.99 $21.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.98

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 26, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

A Next Big Idea Club Winter 2021 Must Read

The ability to connect with another person’s physical and emotional state is one of the most elusive interpersonal skills to develop, but this book shows you just how approachable it can be.

In our fast-paced, tech-obsessed lives, rarely do we pay genuine, close attention to one another. With all that’s going on in the world and the never-ending demands of our daily lives, most of us are too stressed and preoccupied to be able to really listen to each other. Often, we misunderstand or talk past each other. Many of us are left wishing that the people in our lives could really listen, understand, and genuinely connect with us. The ability to connect with another person’s physical and emotional state is one of the most elusive interpersonal skills to develop, but this book shows you just how approachable it can be.

Based on cutting-edge neuroscience research and years of clinical work, psychiatrist Edward Brodkin and therapist Ashley Pallathra take us on a wide-ranging and surprising journey through fields as diverse as social neuroscience and autism research, music performance, pro basketball, and tai chi. They use these stories to introduce the four pillars of human connection: Relaxed Awareness, Listening, Understanding, and Mutual Responsiveness. Accessible and engaging, Missing Each Other explains the science, research, and biology underlying these pillars of human connection and provides exercises through which readers can improve their own skills and abilities in each.

-

“An absolutely compelling perspective on the science and practice of authentic human connection. If you want to know how and why to get in sync with other people, this book is for you. I absolutely loved it!”Angela Duckworth, Ph.D., author of Grit; Founder and CEO, Character Lab; Rosa Lee and Egbert Chang Professor, University of Pennsylvania

-

“In a world dominated by divided attention, the people who stand out are the ones who make us feel like the only person in the room. This book is a thoughtful exploration of how we can strengthen our connections by becoming more attuned to those around us.”Adam Grant, Ph.D., New York Times bestselling author of Think Again and Give and Take, and host of the chart-topping TED podcast WorkLife

-

“If you want more love and meaning in your life, you must read this book. Brodkin and Pallathra give expression to an inchoate yearning more and more people feel today, yet do not know how to fulfill—how to make true contact, with another, which the authors call ‘attunement.’ Combining rigorous scholarship with heart and soul, Brodkin and Pallathra break down the four different pillars that make up a meaningful connection, and show readers, through concrete exercises, how to build those pillars so that we each may have richer, deeper relationships with loved ones, friends, and colleagues.”Emily Esfahani Smith, author of The Power of Meaning

-

“If ever there was a book written for our time, Missing Each Other is it. Paradoxically, all the modern communications technology that has proven so important in the midst of a global pandemic has only reminded us how much we actually miss each other. This book will help us learn those lessons as we escape from our walls and screens.”Jonathan Moreno, Ph.D., author of Everybody Wants to Go to Heaven but Nobody Wants to Die; David and Lyn Silfen University Professor, University of Pennsylvania

-

"In Missing Each Other, the authors, Edward Brodkin and Ashley Pallathra, share how attunement to ourselves and others can have a positive impact on our lives. How often have you walked away from a conversation and wondered how it turned into a disagreement? This book shares insight and activities to help understand each of our parts in creating communications and connections. Especially useful in the time of technology and social distancing."Sharon Salzberg, author of Lovingkindness and Real Change

-

“They write with a passionate, encouraging, come-and-join-me quality, showing how we can find attunement through the exercise of its basic components…A dynamic approach to focusing, connecting, and developing mutual understanding.”Kirkus

-

"Brodkin and Pallathra share helpful advice for fostering meaningful connections in their excellent debut…This refreshing take, devoid of trendy self-care speak, acts as a soothing salve for those anxious in social situations. The result is a highly informed guide on how to be fully present and open with others."Publishers Weekly