Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

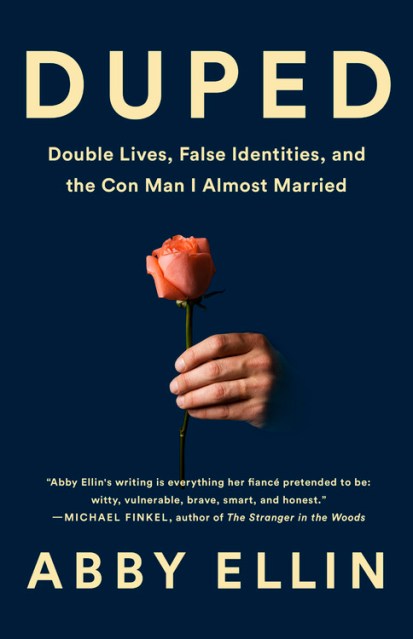

Duped

Double Lives, False Identities, and the Con Man I Almost Married

Contributors

By Abby Ellin

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 15, 2019

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781610398008

Price

$36.00Price

$46.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Hardcover $36.00 $46.00 CAD

- ebook $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 15, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From Abby Ellin’s first date with the Commander, she was caught up in a whirlwind. Within six months he’d proposed, and they’d moved in together. But soon, his exotic stories of international espionage began to unravel. Finally, it all became clear: he was lying about who he was.

After leaving him and sharing her story, she was floored to find out that her experience was far from unique. People everywhere, many of them otherwise sharp-witted and self-aware, are being deceived by their loved ones every day.

In Duped, Abby Ellin studies the art and science of lying, talks to people who’ve had their worlds upended by duplicitous partners, and writes with great openness about her own mistakes. These remarkable stories reveal how often we encounter people whose lives beneath the surface are more improbable than we ever imagined.

-

"I have recommended this one to friends who've loved someone they turned out not to know... [Ellin] pulls off the tricky balancing act of avoiding either self-justification or self-castigation...Reading 'Duped' gave me occasion to second-guess even gentler deceptions; it may actually have made me a (slightly) better person."Tim Kreider, New York Times Book Review

-

Abby Ellin's writing is everything her fiancé pretended to be: witty, vulnerable, brave, smart, and honest.Michael Finkel, author of the National Bestseller, The Stranger in the Woods

-

"Candid and entertaining, Ellin's book offers insight into the socially and psychologically complex nature of deceit as well as the choices she made as a duped woman. Lively, provocative reading."Kirkus Reviews

-

"The author's hybrid of memoir and journalism works well for general readers, keeping things engaging and witty...A timely book for folks who wonder how we ended up in this post-truth world as well as readers of bookslike A Beautiful, Terrible Thing (2017) by Jen Waite."Booklist

-

"Abby Ellin has been Duped, and in this fascinating book, she reveals how and why ordinary people are often deceived by extraordinarily mendacious con artists. Ellin's personal story leads her to delve deep into research of why people lie and how they lie, and she discovers how common treachery can be. If you've ever been lied to, or told a lie, you will want to read this surprising, personal, and funny investigation of deception."Piper Kerman, #1 New York Times bestselling author of Orange is the New Black

-

"I couldn't put it down!"Gretchen Rubin, #1 New York Times bestselling author of The Happiness Project and The Four Tendencies

-

"From the wildly entertaining opening chapter of Duped, Abby Ellin explores the why and how of great imposters, many of whom occupied important swaths of her life. Swerving from the deceitful, manipulative, pathological narcissists to the professional use of lie detectors, she makes researching dishonesty an entertaining and fascinating read."Jonna HiestandMendez, former CIA chief of disguise

-

"I loved this book, and not just because of Abby Ellin's masterful storytelling. This is a book that can save lives. She paints an exquisite portrait of what life with a predator is like. No child should go to college without first reading this book."Joe Navarro, formerFBI agent and bestselling author of Dangerous Personalities

-

"Thrilling, weird, and funny, Duped reveals the psychology of gaslighting, the prevalence of gullibility, and the wisdom in paranoia. Abby Ellin is a shrewd chronicler of cons and a gracious friend to the duped."Ada Calhoun, authorof Wedding Toasts I'll Never Give