Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

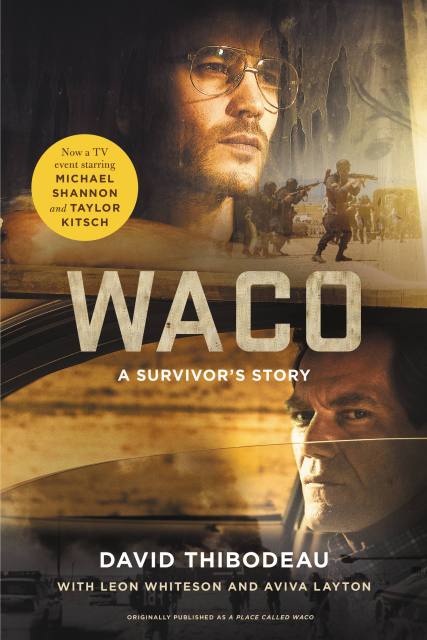

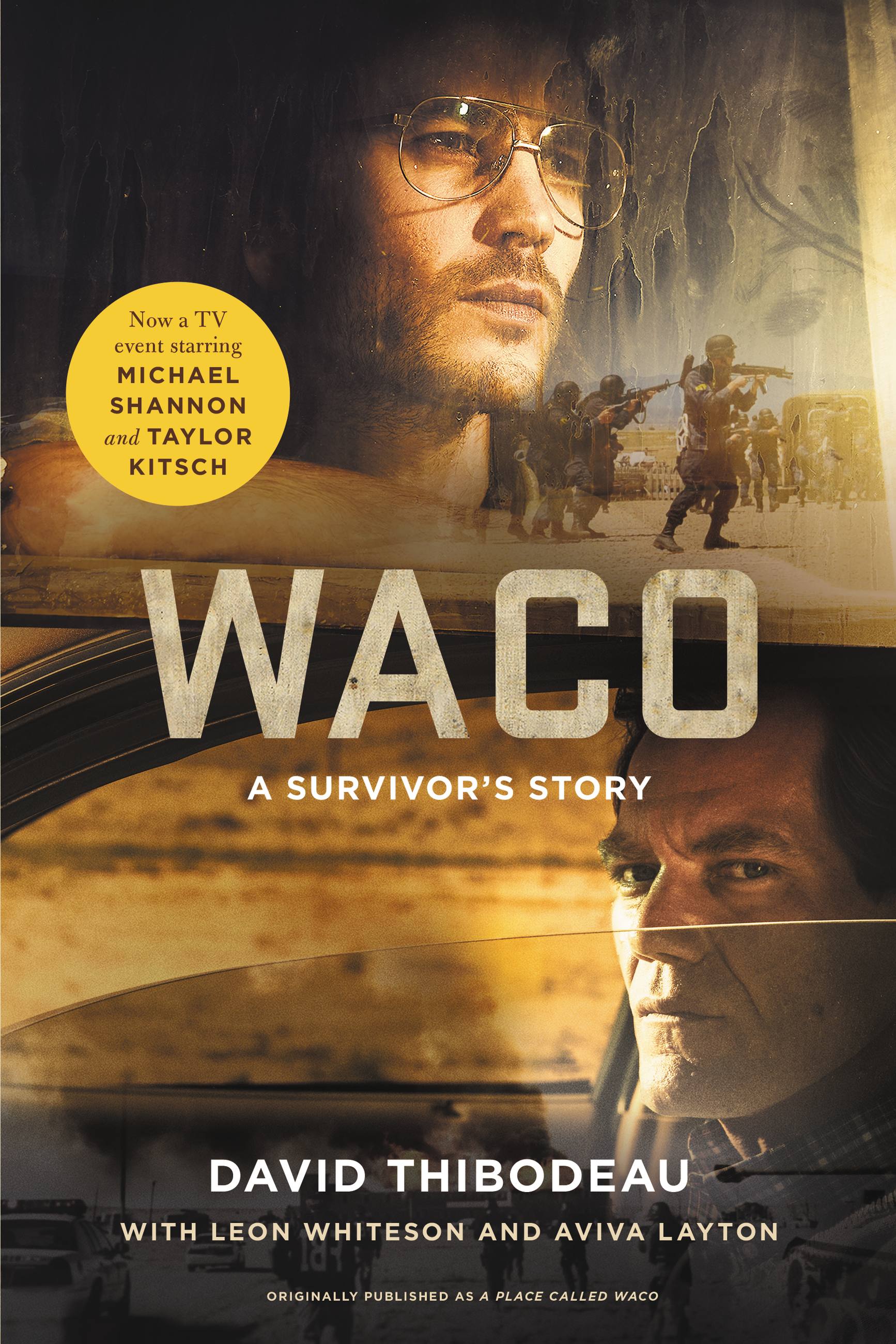

Waco

A Survivor's Story

Contributors

By Leon Whiteson

With Aviva Layton

Formats and Prices

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 2, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Twenty-five years ago, the FBI staged a deadly raid on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco. Texas. David Thibodeau survived to tell the story.

When he first met the man who called himself David Koresh, David Thibodeau was a drummer in a local a rock band. Though he had never been religious in the slightest, Thibodeau gradually became a follower and moved to the Branch Davidian compound in Waco. He remained there until April 19, 1993, when the compound was stormed and burned to the ground after a 51-day standoff with government authorities.

In this compelling account — now with an updated epilogue that revisits remaining survivors–Thibodeau explores why so many people came to believe that Koresh was divinely inspired. We meet the men, women, and children of Mt. Carmel. We get inside the day-to-day life of the community. We also understand Thibodeau’s brutally honest assessment of the United States government’s actions. The result is a memoir that reads like a thriller, with each page taking us closer to the eventual inferno.

Genre:

-

"An extraordinary account of one of the most shameful episodes in recent American history. I wish that everyone in the country could read this book."Howard Zinn

-

"This book gives a rare glimpse of life at Mount Carmel and an account of how that attack contrasts with the 'official' government version. With the renewed interest in this siege, this book is recommended for public libraries."School Library Journal

-

"This narrative defies many of our media-mediated preconceptions of Koresh's followers."Booklist

-

"Thibodeau, one of only four Branch Davidians to live through the Waco disaster and not be sentenced to jail, has produced a surprisingly balanced and honest account of his time as a Branch Davidian. Neither sensationalist nor defensive, this will make satisfying reading for anyone interested in the April 1993 tragedy."Kirkus Review

-

"A disquieting portrait of a religious community and its enigmatic leader."Kirkus Reviews

-

"Honest... [about] whether the excessive force used by our government against American citizens was really necessary."Lincoln Star Journal

- On Sale

- Jan 2, 2018

- Page Count

- 400 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9781602865761

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use