By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

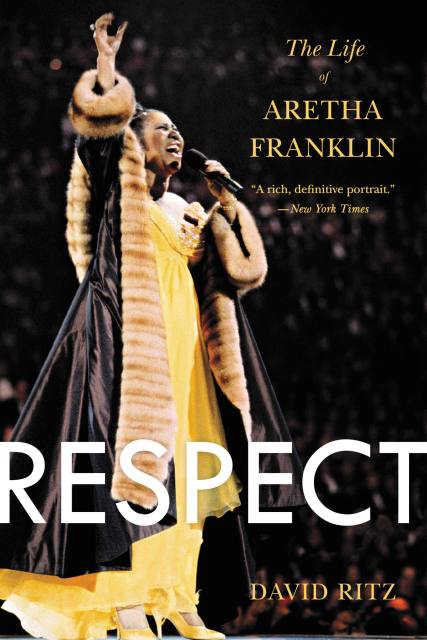

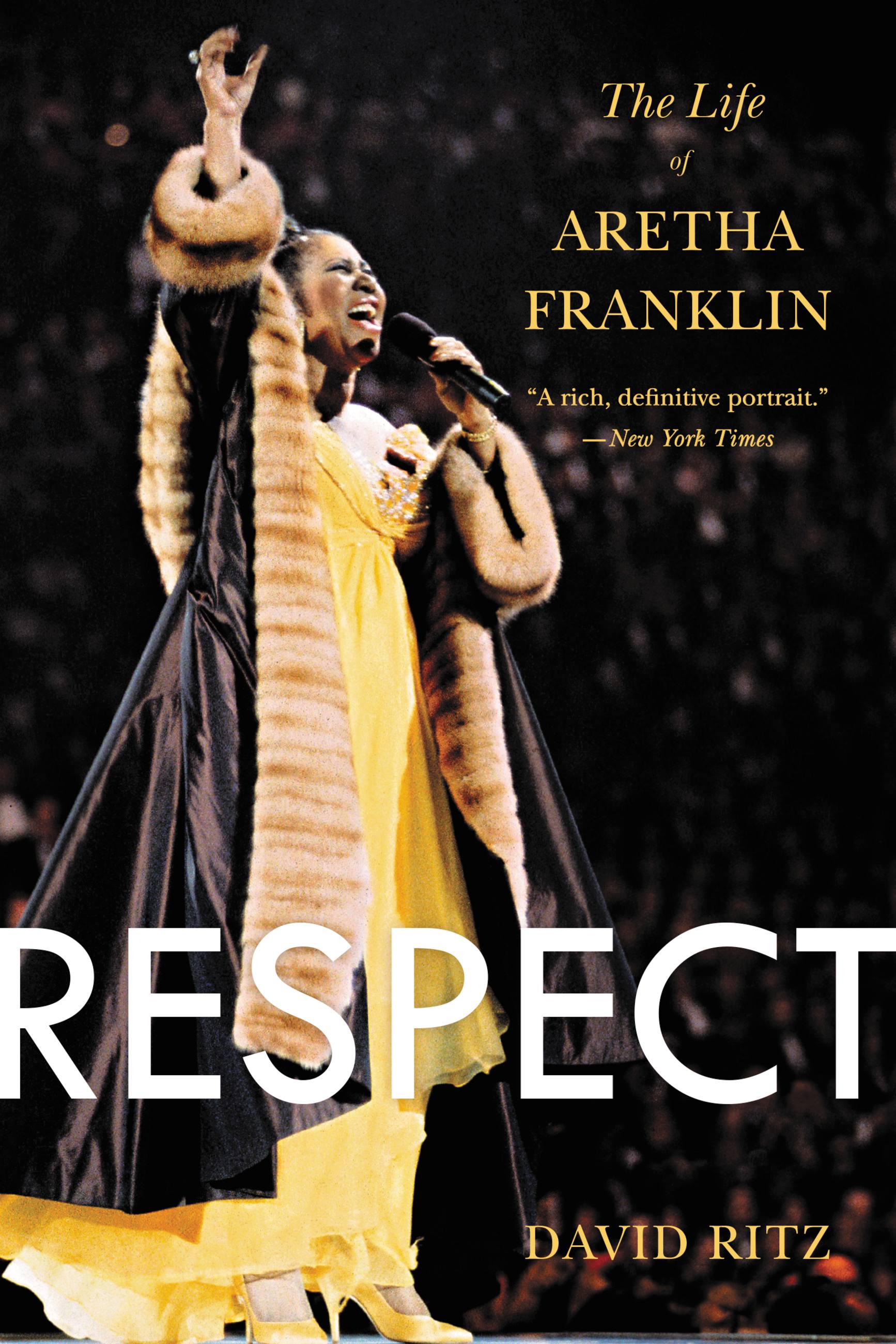

Respect

The Life of Aretha Franklin

Contributors

By David Ritz

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Oct 28, 2014

- Page Count

- 528 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316196826

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around October 28, 2014. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This “comprehensive and illuminating” biography of the Queen of Soul (USA Today) was hailed by Rolling Stone as “a remarkably complex portrait of Aretha Franklin’s music and her tumultuous life.”

Aretha Franklin began life as the golden daughter of a progressive and promiscuous Baptist preacher. Raised without her mother, she was a gospel prodigy who gave birth to two sons in her teens and left them and her native Detroit for New York, where she struggled to find her true voice. It was not until 1967, when a white Jewish producer insisted she return to her gospel-soul roots, that fame and fortune finally came via “Respect” and a rapidfire string of hits. She continued to evolve for decades, amidst personal tragedy, surprise Grammy performances, and career reinventions.

Again and again, Aretha stubbornly found a way to triumph over troubles, even as they continued to build. Her hold on the crown was tenacious, and in Respect, David Ritz gives us the definitive life of one of the greatest talents in all American culture.

-

"An honest and genuinely respectful portrait of a true diva by a writer who feels the power of her art."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

"Ritz's intimate and elegant voice steps from behind the veil of the ghostwriter to tell a tale of genius, dysfunction and blind ambition, describing a world of triumph and tragedy of near mythic proportions. A great read and a really heroic work of biography -- honest, loving, no holds barred."Ben Sidran, author of There Was a Fire

-

"The monumental biography we've been waiting for of Lady Soul, our greatest soul singer, from the also very great David Ritz, confidante to an entire generation of soul stars -- Ray, Smokey, B.B., Etta, Marvin, etcetera. He is The Man. This is The Book."Joel Selvin, author of Here Comes the Night: The Dark Soul of Bert Berns and the Dirty Business of Rhythm and Blues

-

"This far surpasses David Ritz's landmark study of Marvin Gaye. People will be reading Respect generations from now to understand our musical culture. Ritz deserves a lifetime achievement award for "Most Soul Full Account of America's Music."Charles Keil, ethnomusicologist, author of Urban Blues

-

"Only someone who had the complete confidence and trust of Aretha's family and the elite of the Gospel and Rhythm and Blues communities could have gotten this story. An intimate and thorough account of this phenomenal woman's talent and life as only David Ritz could capture."Tommy LiPuma, Grammy-winning producer

-

"A bumpy and delicious ride.... Read Respect with a YouTube-playing device near at hand to experience Aretha in a hundred shades of glorious."Claude Peck, Minneapolis Star Tribune

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use