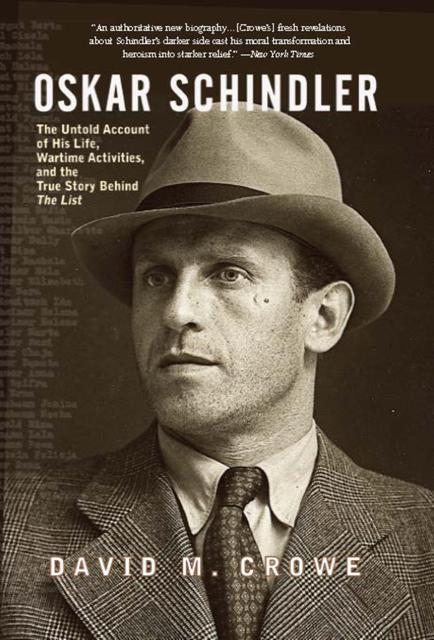

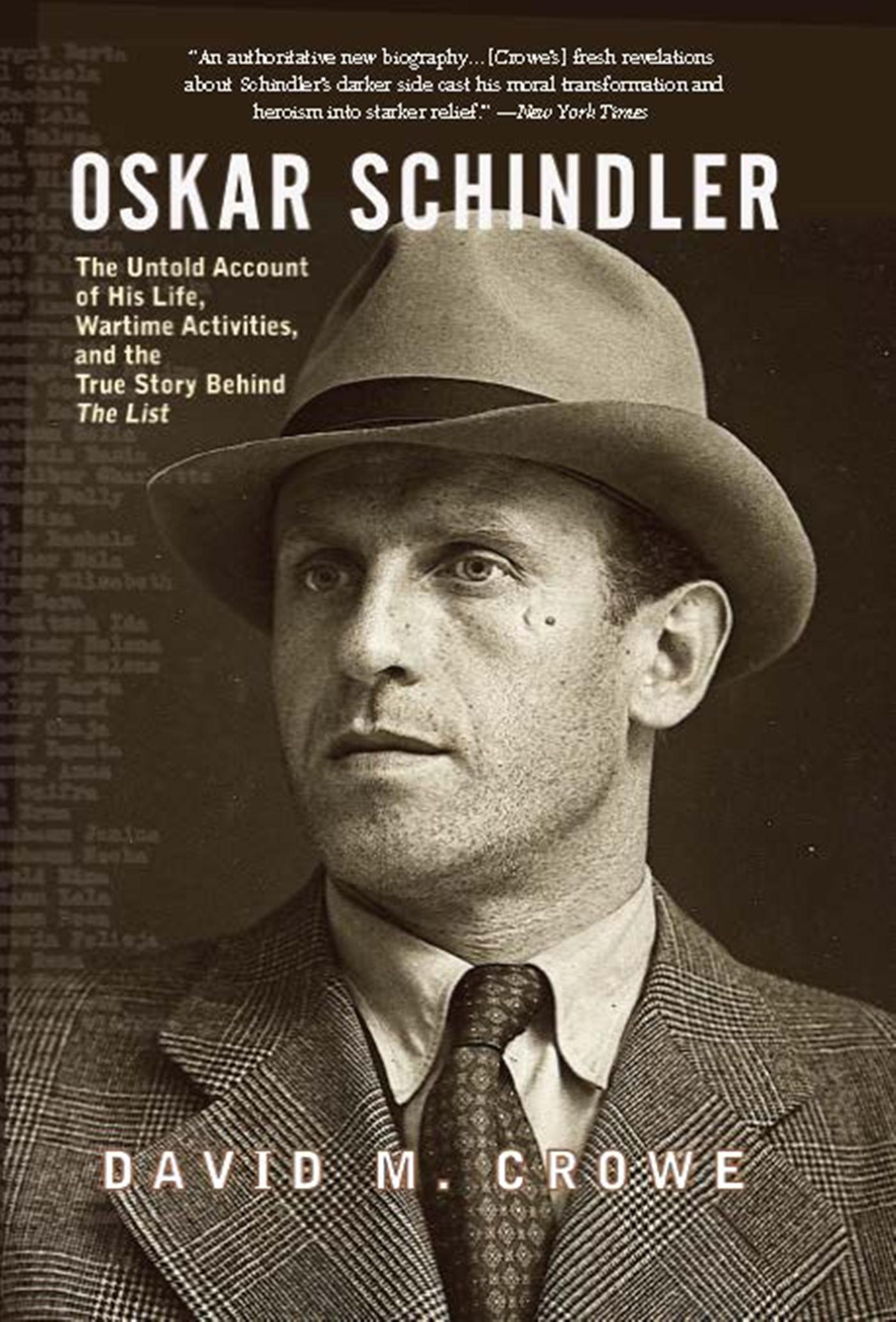

Oskar Schindler

The Untold Account of His Life, Wartime Activities, and the True Story Behind the List

Contributors

By David Crowe

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $14.99 $19.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around August 1, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Genre:

- On Sale

- Aug 1, 2007

- Page Count

- 800 pages

- Publisher

- Basic Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780465008490

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use