Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

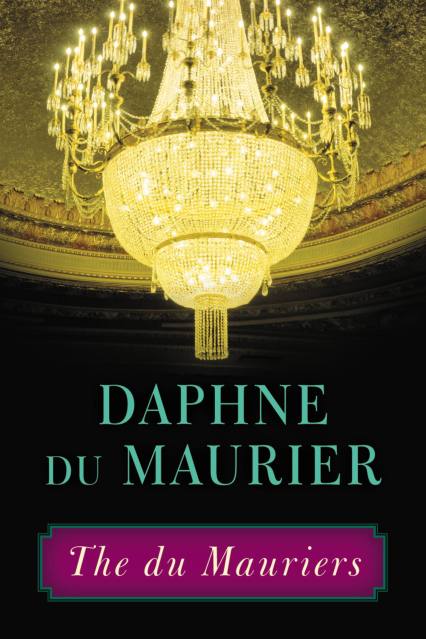

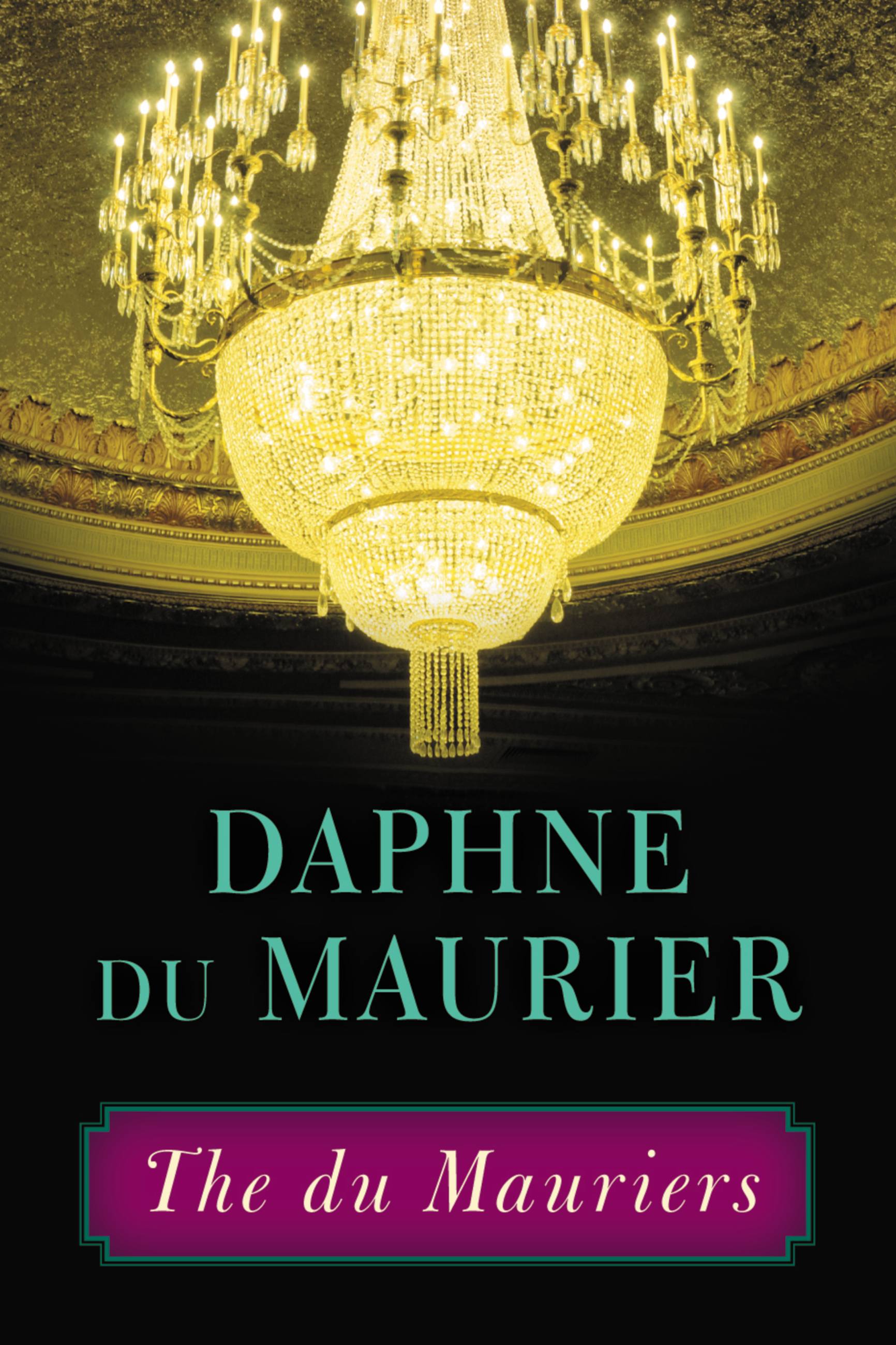

The du Mauriers

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Format

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $9.99This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 17, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Spanning nearly three quarters of a century, The du Mauriers is a saga of artists and speculators, courtesans and military men. From England to Paris and back again, their fortunes varied as wildly as their ambitions. An extraordinary family of writers, artists and actors they are…The du Mauriers.

“Daphne du Maurier creates on the grand scale; she runs through the generations, giving her family unity and reality . . . a rich vein of humor and satire . . . observation, sympathy, courage, a sense of the romantic, are here.”-The Observer

Genre:

- On Sale

- Dec 17, 2013

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316254366

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use