By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

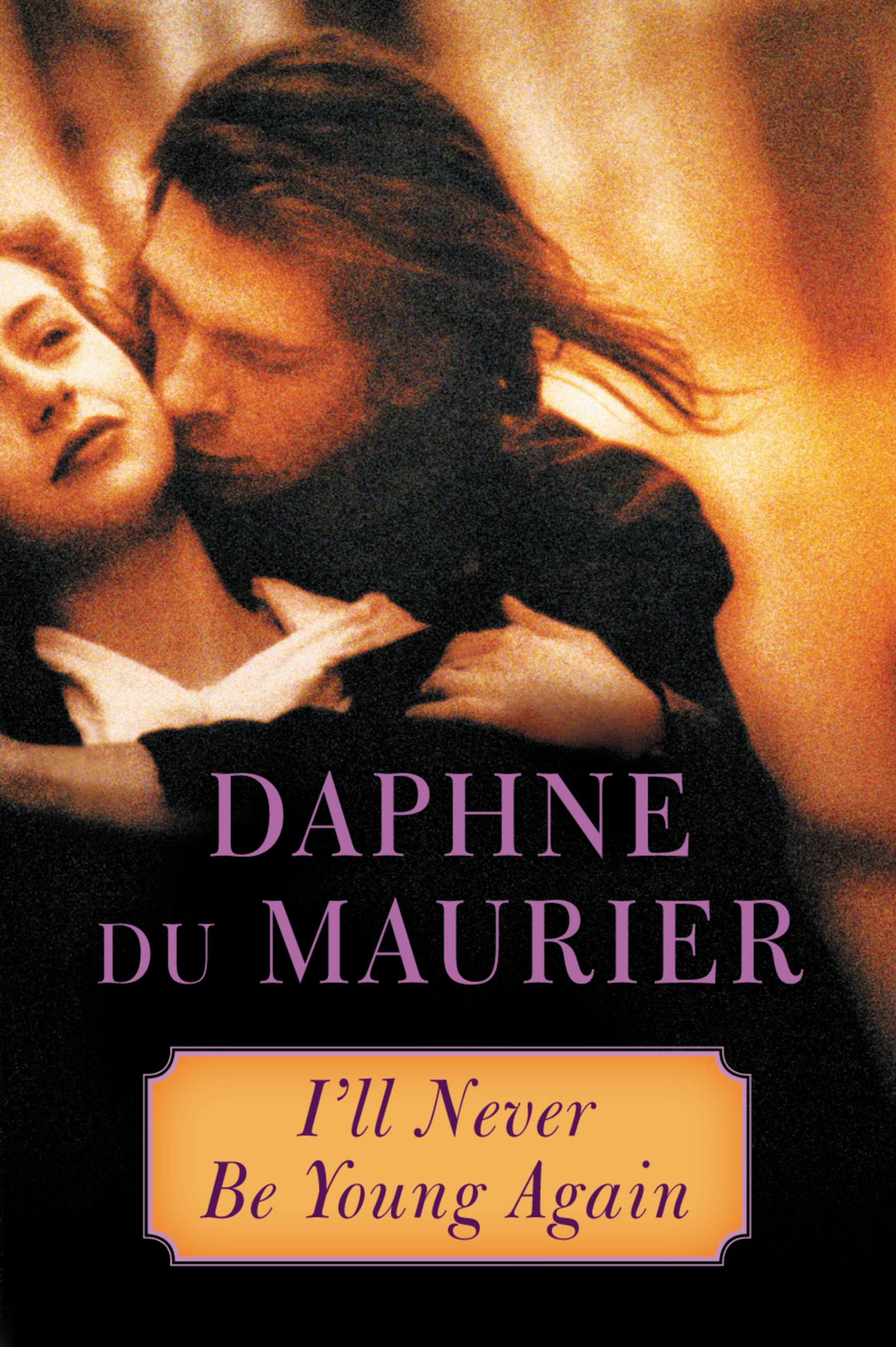

I’ll Never Be Young Again

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 17, 2013

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316253567

Price

$6.99Format

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $6.99This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 17, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As far as his father, a famous writer, is concerned, Richard will never amount to anything, and so he decides to take his fate into his own hands. But at the last moment he is saved by Jake, who appeals to Richard not to waste his life. Together they set out for adventure, working their way through Europe, eventually arriving in bohemian Paris, where Richard meets Hesta, an entrancing music student.

Daphne du Maurier’s second novel is a masterpiece of narration, showcasing for the first time in her career the male voice she would use to stunning effect in four subsequent novels, including My Cousin Rachel.

“A magician, a virtuoso. She can conjure up tragedy, horror, tension, suspense, the ridiculous, the vain, the romantic.”-Good Housekeeping

Daphne du Maurier’s second novel is a masterpiece of narration, showcasing for the first time in her career the male voice she would use to stunning effect in four subsequent novels, including My Cousin Rachel.

“A magician, a virtuoso. She can conjure up tragedy, horror, tension, suspense, the ridiculous, the vain, the romantic.”-Good Housekeeping

Genre:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use