Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

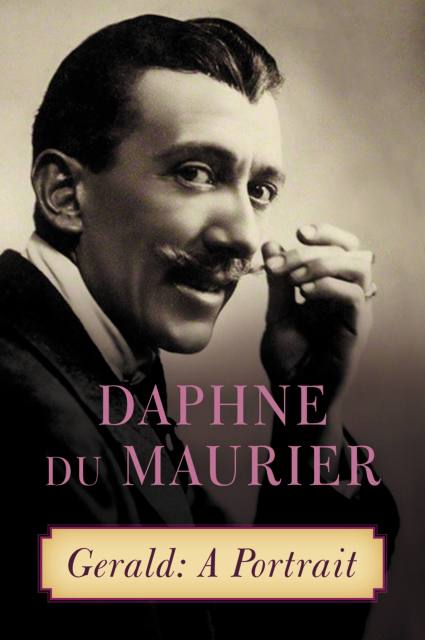

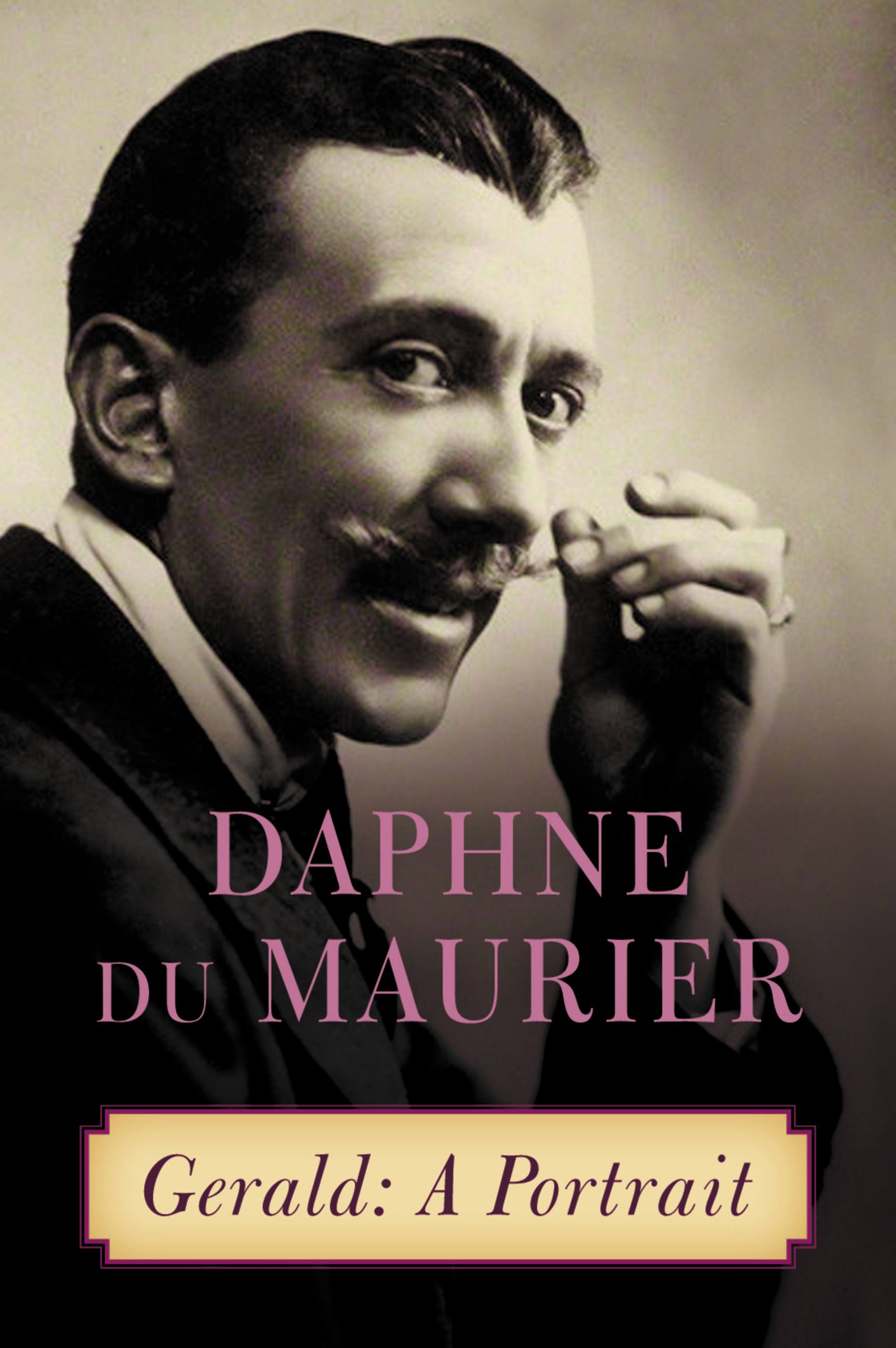

Gerald

A Portrait

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Format

Format:

ebook (Digital original) $9.99This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 17, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

Sir Gerald du Maurier was the preeminent actor-manager of his day, knighted in 1922 for his services to the theater. Published within six months of her father’s death, Daphne du Maurier’s frank portrait was considered shocking by many of his admirers-but it was a huge success, winning her critical acclaim and launching her career. Here, Daphne captures the spirit and charm of the charismatic actor who played the original Captain Hook, amusingly recounting his eccentricities, his humor, as well as his darker side.

“A remarkable book…brilliant comic writing.”-The Times (UK)

“A remarkable book…brilliant comic writing.”-The Times (UK)

Genre:

- On Sale

- Dec 17, 2013

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316253666

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use