Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

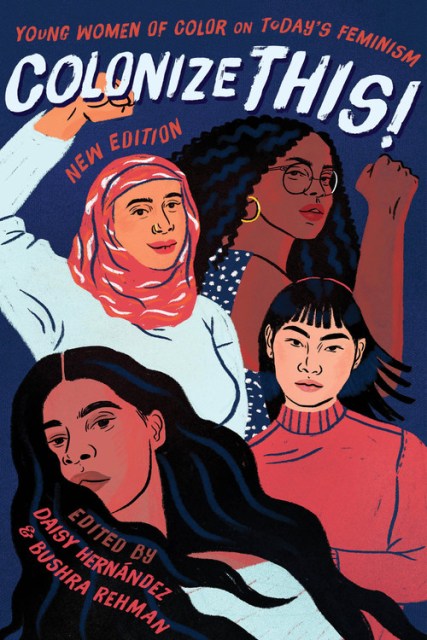

Colonize This!

Young Women of Color on Today's Feminism

Contributors

Edited by Daisy Hernández

Edited by Bushra Rehman

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 16, 2019

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580057769

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback (New edition) $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook (New edition) $13.99 $17.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 16, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Newly revised and updated, this landmark anthology offers gripping portraits of American life as seen through the eyes of young women of color

It has been decades since women of color first turned feminism upside down, exposing the feminist movement as exclusive, white, and unaware of the concerns and issues of women of color from around the globe. Since then, key social movements have risen, including Black Lives Matter, transgender rights, and the activism of young undocumented students. Social media has also changed how feminism reaches young women of color, generating connections in all corners of the country. And yet we remain a country divided by race and gender.

Now, a new generation of outspoken women of color offer a much-needed fresh dimension to the shape of feminism of the future. In Colonize This!, Daisy Hernandez and Bushra Rehman have collected a diverse, lively group of emerging writers who speak to the strength of community and the influence of color, to borders and divisions, and to the critical issues that need to be addressed to finally reach an era of racial freedom. With prescient and intimate writing, Colonize This! will reach the hearts and minds of readers who care about the experience of being a woman of color, and about establishing a culture that fosters freedom and agency for women of all races.

Series:

-

One of "18 Books Every White Ally Should Read"Bustle

-

One of "19 Books on Intersectionality that Taylor Swift Should Read"BuzzFeed

-

One of "13 books Every Mujerista and Womanist Should Read"Vibe

-

One of the "100 Best Non-Fiction Books of All Time"MS.

-

"These contemporary 'sistah outsiders' don't shy away from sticky issues when addressing the complexities of their lives. Refusing to simplify in order to fit into someone's mold, these women dare you to dismiss them."Bust

-

"This is one of those books which should be required reading for every young sister out there."Asian Weed

-

"These women express a more radical, racialized feminism that broadens the movement beyond its early incarnation."Booklist