By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

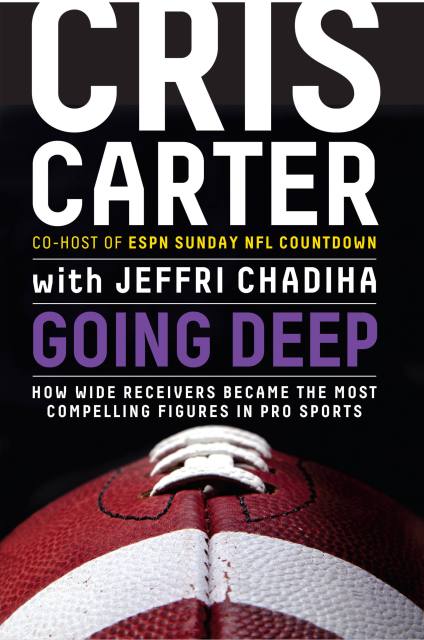

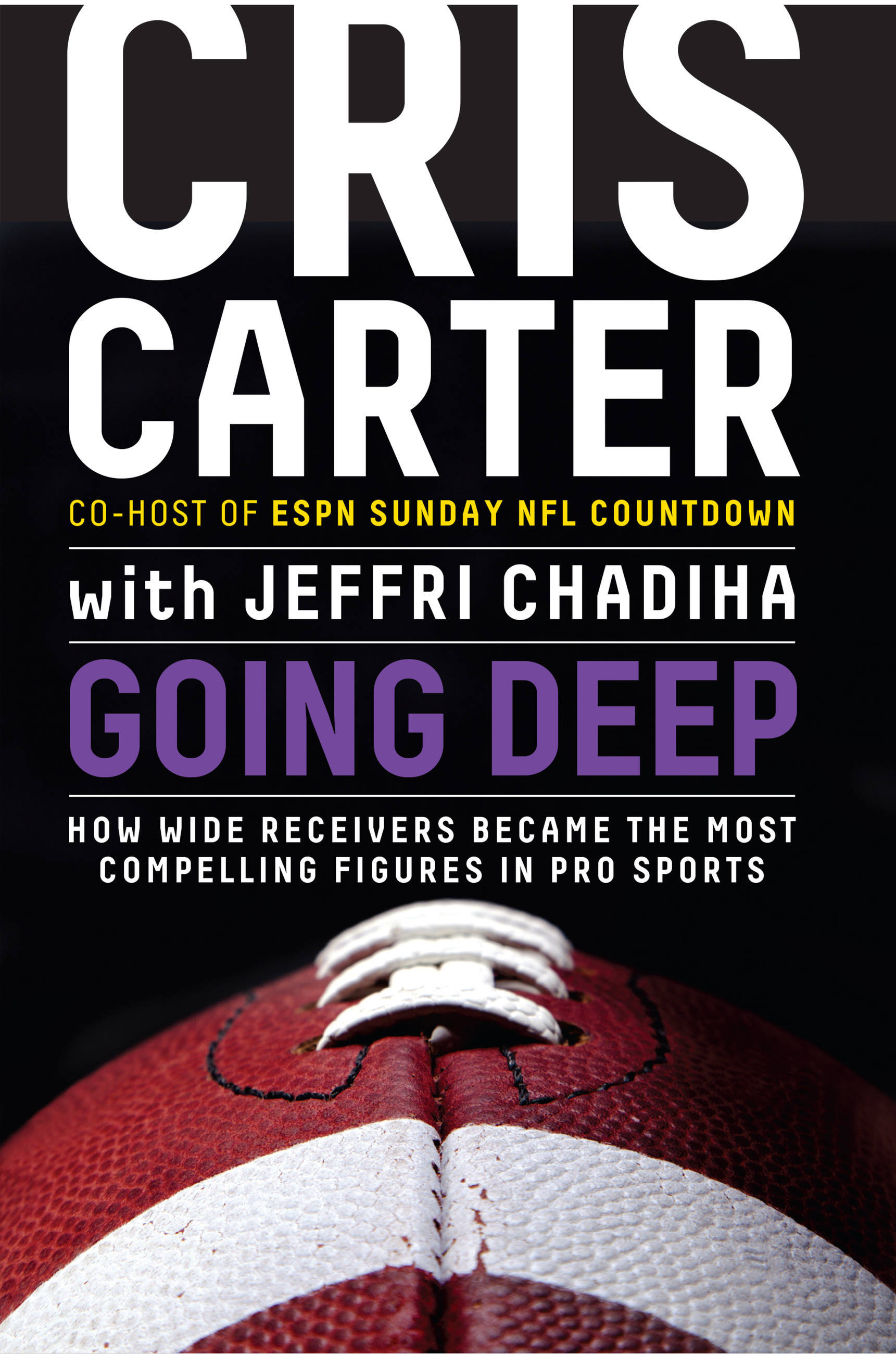

Going Deep

How Wide Receivers Became the Most Compelling Figures in Pro Sports

Contributors

By Cris Carter

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 30, 2013

- Page Count

- 304 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9781401305468

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

ebook $12.99 $16.99 CADThis item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 30, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From the time Cris Carter started his career as a supplemental draft pick of the Philadelphia Eagles in 1987 to his retirement in 2002, the position of wide receiver exploded in the NFL. Receivers went from being quiet and classy to being known for their electric play, off-the-field antics, and — in some cases — over-the-top personalities.

In Going Deep, Carter and ESPN journalist Jeffri Chadiha chronicle the rise of the wide receiver and explain how it became the most complex, compelling, and talked-about position in all of professional sports. Using stories from his own career to offer unprecedented insight into the position, Carter explains the players’ unique personalities, how their minds work, and why teams need to understand exactly what they’re dealing with when it comes to their wideouts — the NFL’s newest superstars.

Told through Carter’s opinionated voice, Going Deep covers all the important moments and people — from Michael Irvin, Jerry Rice, and Keyshawn Johnson to Randy Moss, Terrell Owens, and Chad Johnson — who have contributed to this revolution. He also tells stories readers have never heard about their favorite players, shares theories about the position that only get discussed in front offices and locker rooms, and offers revealing explanations on what these players mean to the league today, as well as why the NFL can’t go forward without them.

“One of the most riveting, insightful football books I’ve ever read. This book takes you inside the huddle, along the sidelines, and deep into the secret world that is the NFL. Breathtaking work.” — Jeff Pearlman, New York Times bestselling author of Boys Will Be Boys and The Bad Guys Won

“No one understands wide receivers better than Cris Carter, and I loved his book. If you want to understand how we think, and hear inside stories about the most over-the-top athletes in sports, read Going Deep.” — Jerry Rice, Hall of Fame wide receiver

“I am so glad someone got Cris Carter to sit down and describe what makes receivers tick. (It’s deeper than you think.) You’ll get to the last page of this book and say, ‘I really learned a lot here–and the pages flew by.’ ” — Peter King, senior writer, Sports Illustrated; author of Monday Morning Quarterback; and two-time National Sportswriter of the Year

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use