By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

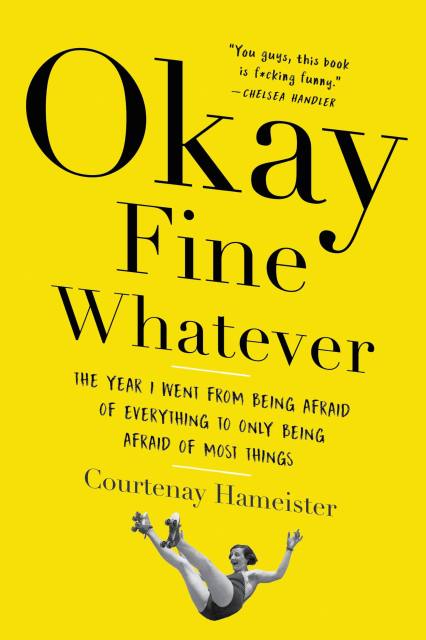

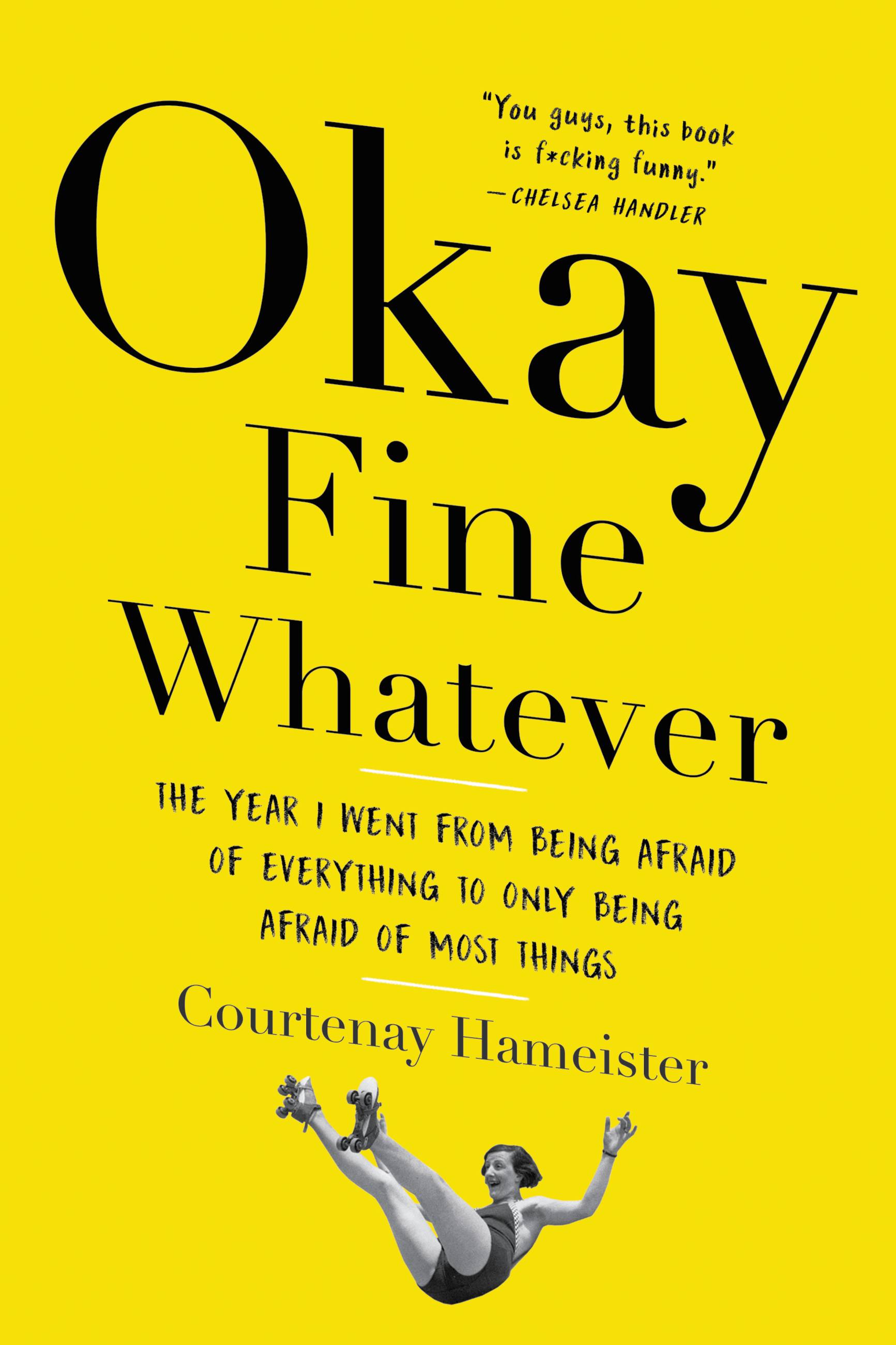

Okay Fine Whatever

The Year I Went from Being Afraid of Everything to Only Being Afraid of Most Things

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jul 31, 2018

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316395694

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $16.99 $22.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around July 31, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The “hilarious and poignant” story of one chronically anxious woman’s quest to become braver by seeking out the kinds of experiences she’s spent her life avoiding (Cheryl Strayed).

For most of her life (and even during her years as the host of a popular radio show), Courtenay Hameister lived in a state of near-constant dread and anxiety. She fretted about everything. Her age. Her size. Her romantic prospects. How likely it was that she would get hit by a bus on the way home.

Until a couple years ago, when, in her mid-forties, she decided to fight back against her debilitating anxieties by spending a year doing little things that scared her — things that the average person might consider doing for a half second before deciding: “nope.”

Things like: attending a fellatio class. She did that. She also spent an afternoon in a sensory deprivation tank, got (legally) high in the middle of a workday, had a session with a professional cuddler, braved twenty-eight first dates, and (perhaps scariest of all) actually met someone who might possibly appreciate her for who she is.

Refreshing, relatable, and pee-your-pants funny, Okay Fine Whatever is Courtenay’s hold-nothing-back account of her adventures on the front lines of Mere Human Woman vs. Fear, reminding us that even the tiniest amount of bravery is still bravery, and that no matter who you are, it’s possible to fight complacency and become bold, or at least bold-ish, a little at a time.

For most of her life (and even during her years as the host of a popular radio show), Courtenay Hameister lived in a state of near-constant dread and anxiety. She fretted about everything. Her age. Her size. Her romantic prospects. How likely it was that she would get hit by a bus on the way home.

Until a couple years ago, when, in her mid-forties, she decided to fight back against her debilitating anxieties by spending a year doing little things that scared her — things that the average person might consider doing for a half second before deciding: “nope.”

Things like: attending a fellatio class. She did that. She also spent an afternoon in a sensory deprivation tank, got (legally) high in the middle of a workday, had a session with a professional cuddler, braved twenty-eight first dates, and (perhaps scariest of all) actually met someone who might possibly appreciate her for who she is.

Refreshing, relatable, and pee-your-pants funny, Okay Fine Whatever is Courtenay’s hold-nothing-back account of her adventures on the front lines of Mere Human Woman vs. Fear, reminding us that even the tiniest amount of bravery is still bravery, and that no matter who you are, it’s possible to fight complacency and become bold, or at least bold-ish, a little at a time.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use