Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

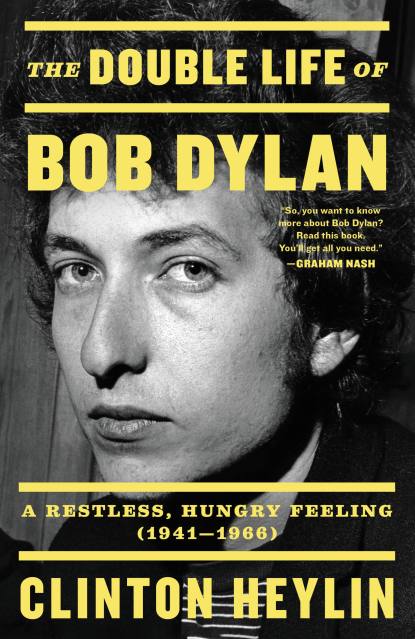

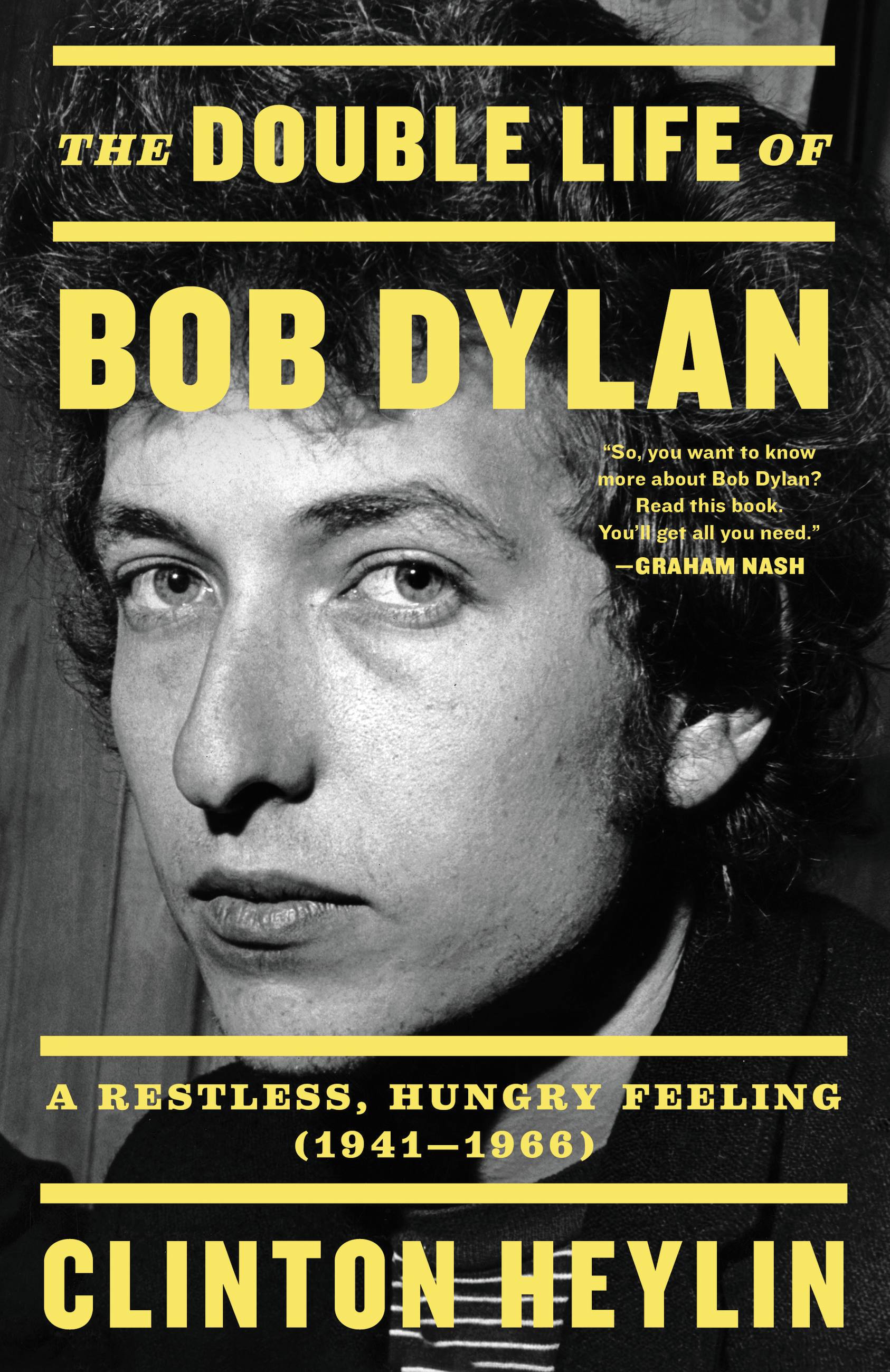

The Double Life of Bob Dylan

A Restless, Hungry Feeling, 1941-1966

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $30.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around May 18, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

From the world's leading authority on Bob Dylan comes the definitive biography that promises to transform our understanding of the man and musician—thanks to early access to Dylan's never-before-studied archives.

In 2016 Bob Dylan sold his personal archive to the George Kaiser Foundation in Tulsa, Oklahoma, reportedly for $22 million. As the boxes started to arrive, the Foundation asked Clinton Heylin—author of the acclaimed Bob Dylan: Behind the Shades and 'perhaps the world's authority on all things Dylan' (Rolling Stone)—to assess the material they had been given. What he found in Tulsa—as well as what he gleaned from other papers he had recently been given access to by Sony and the Dylan office—so changed his understanding of the artist, especially of his creative process, that he became convinced that a whole new biography was needed. It turns out that much of what previous biographers—Dylan himself included—have said is wrong.

With fresh and revealing information on every page A Restless, Hungry Feeling tells the story of Dylan's meteoric rise to fame: his arrival in early 1961 in New York, where he is embraced by the folk scene; his elevation to spokesman of a generation whose protest songs provide the soundtrack for the burgeoning Civil Rights movement; his alleged betrayal when he 'goes electric' at Newport in 1965; his subsequent controversial world tour with a rock 'n' roll band; and the recording of his three undisputed electric masterpieces: Bringing it All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. At the peak of his fame in July 1966 he reportedly crashes his motorbike in Woodstock, upstate New York, and disappears from public view. When he re-emerges, he looks different, his voice sounds different, his songs are different.

Clinton Heylin's meticulously researched, all-encompassing and consistently revelatory account of these fascinating early years is the closest we will ever get to a definitive life of an artist who has been the lodestar of popular culture for six decades.

Genre:

-

“So, you want to know more about Bob Dylan? Read Clinton Heylin’s new book. You’ll get all you need.”Graham Nash

-

“Whether you’ve read one book on Bob Dylan or one hundred, this is the one you want to read and refer to from this day forward. It leaps a couple light-years ahead with much newly revealed material and deep scholarship. If somebody’s got to tell the tale, we can all thank our holy electric pickups and mystical typewriter keys that it was up to Clinton Heylin.”Lee Ranaldo, Sonic Youth

-

“If you really want to know the story of Bob Dylan (and everybody should), this is where you must start.”Robert Hillburn, author of Johnny Cash

-

“Impressively researched, this deep look at Dylan’s early career and initial stardom is …an enjoyable ride.”Kirkus Reviews

- On Sale

- May 18, 2021

- Page Count

- 704 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316535236

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use