By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

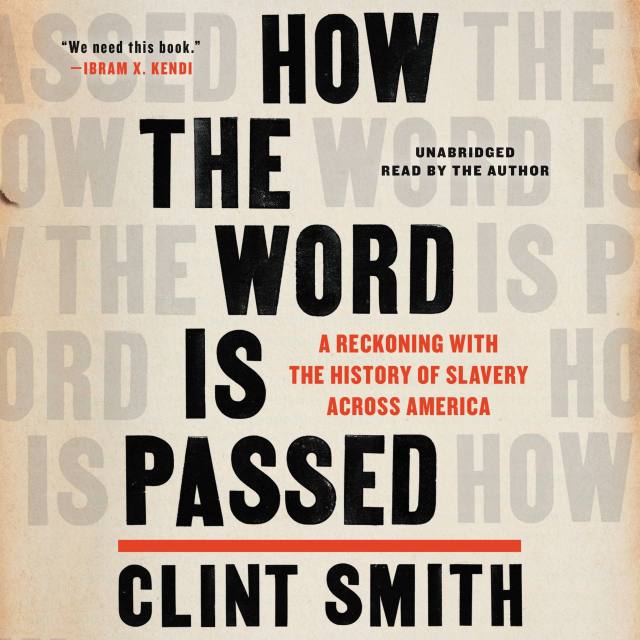

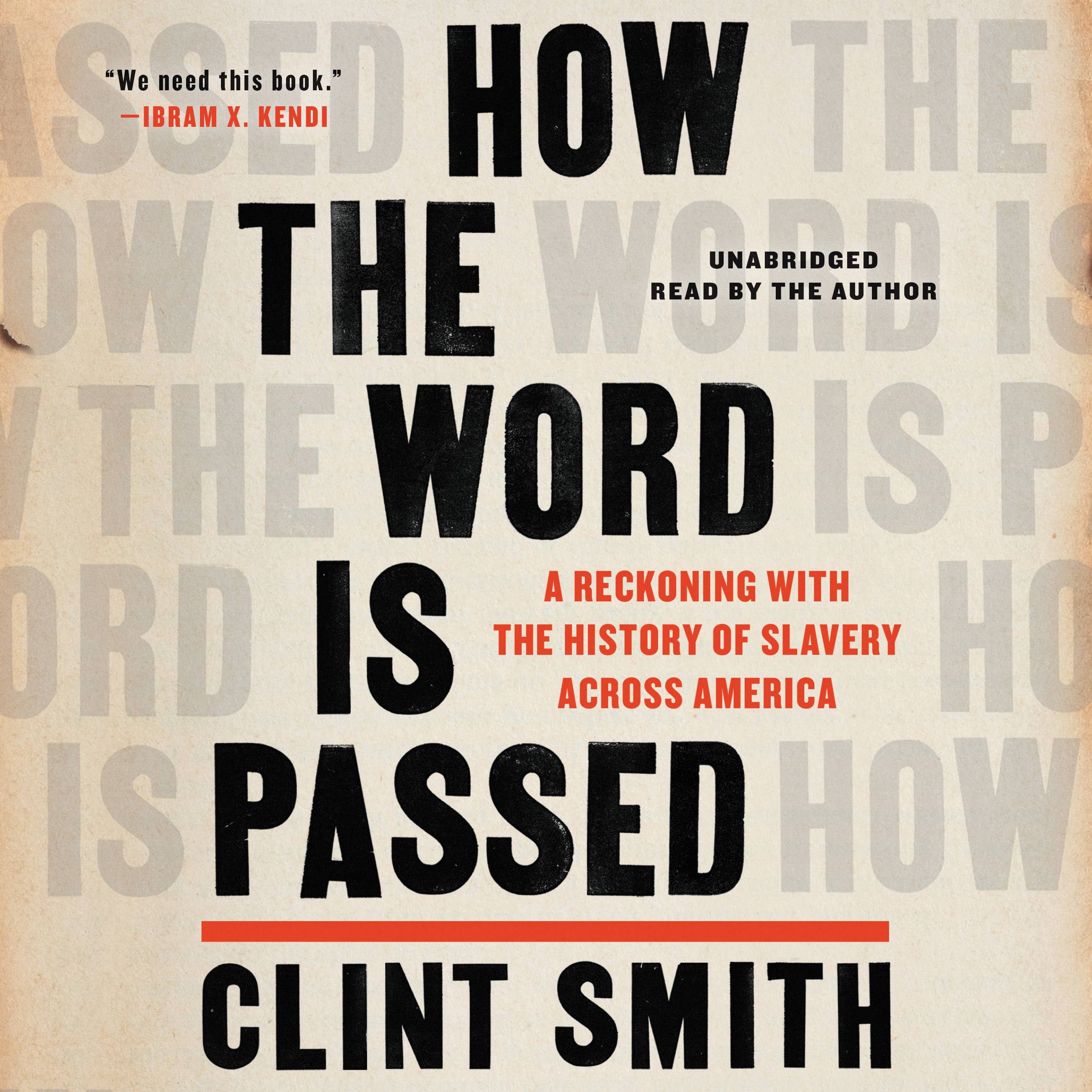

How the Word Is Passed

A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America

Contributors

By Clint Smith

Read by Clint Smith

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 1, 2021

- Publisher

- Hachette Audio

- ISBN-13

- 9781549123405

Price

$40.00Price

$50.00 CADFormat

Format:

- Audiobook CD (Unabridged) $40.00 $50.00 CAD

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover (Large Print) $44.00 $55.00 CAD

- Hardcover $30.00 $40.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 1, 2021. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

This compelling #1 New York Times bestseller examines the legacy of slavery in America—and how both history and memory continue to shape our everyday lives.

Beginning in his hometown of New Orleans, Clint Smith leads the reader on an unforgettable tour of monuments and landmarks—those that are honest about the past and those that are not—that offer an intergenerational story of how slavery has been central in shaping our nation’s collective history, and ourselves.

It is the story of the Monticello Plantation in Virginia, the estate where Thomas Jefferson wrote letters espousing the urgent need for liberty while enslaving more than four hundred people. It is the story of the Whitney Plantation, one of the only former plantations devoted to preserving the experience of the enslaved people whose lives and work sustained it. It is the story of Angola, a former plantation-turned-maximum-security prison in Louisiana that is filled with Black men who work across the 18,000-acre land for virtually no pay. And it is the story of Blandford Cemetery, the final resting place of tens of thousands of Confederate soldiers.

A deeply researched and transporting exploration of the legacy of slavery and its imprint on centuries of American history, How the Word Is Passed illustrates how some of our country’s most essential stories are hidden in plain view—whether in places we might drive by on our way to work, holidays such as Juneteenth, or entire neighborhoods like downtown Manhattan, where the brutal history of the trade in enslaved men, women, and children has been deeply imprinted.

Informed by scholarship and brought to life by the story of people living today, Smith’s debut work of nonfiction is a landmark of reflection and insight that offers a new understanding of the hopeful role that memory and history can play in making sense of our country and how it has come to be.

Instant #1 New York Times Bestseller

Winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award for Nonfiction

Winner of the Stowe Prize

Winner of 2022 Hillman Prize for Book Journalism

PEN America 2022 John Kenneth Galbraith Award for Nonfiction Finalist

A New York Times 10 Best Books of 2021

A Time 10 Best Nonfiction Books of 2021

Named a Best Book of 2021 by The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, The Economist, Smithsonian, Esquire, Entropy, The Christian Science Monitor, WBEZ’s Nerdette Podcast, TeenVogue, GoodReads, SheReads, BookPage, Publishers Weekly, Kirkus, Fathom Magazine, the New York Public Library, and the Chicago Public Library

One of GQ’s 50 Best Books of Literary Journalism of the 21st Century

Longlisted for the National Book Award Los Angeles Times, Best Nonfiction Gift

One of President Obama’s Favorite Books of 2021

-

"Suffused with lyrical descriptions and incisive historical details, including Robert E. Lee’s ruthlessness as a slave owner and early resistance by Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. Du Bois to the Confederate general’s “deification,” this is an essential consideration of how America’s past informs its present."Publisher's Weekly

-

"The Atlantic writer drafts a history of slavery in this country unlike anything you’ve read before.”Entertainment Weekly

-

“An important and timely book about race in America.”Drew Faust, Harvard Magazine

-

"Merging memoir, travelogue, and history, Smith fashions an affecting, often lyrical narrative of witness."The New York Review of Books

-

"In this exploration of the ways we talk about — and avoid talking about — slavery, Smith blends reportage and deep critical thinking to produce a work that interrogates both history and memory."Kate Tuttle, Boston Globe

-

“Raises questions that we must all address, without recourse to wishful thinking or the collective ignorance and willful denial that fuels white supremacy.”Martha Anne Toll, The Washington Post

-

“Sketches an impressive and deeply affecting human cartography of America’s historical conscience…an extraordinary contribution to the way we understand ourselves.”Julian Lucas, New York Times Book Review

-

"With careful research, scholarship, and perspective, Smith underscores a necessary truth: the imprint of slavery is unyieldingly present in contemporary America, and the stories of its legacy, of the enslaved people and their descendants, are everywhere."TeenVogue

-

“Clint Smith, in his new book “How the Word Is Passed,” has created something subtle and extraordinary.”Christian Science Monitor

-

"Part of what makes this book so brilliant is its bothandedness. It is both a searching historical work and a journalistic account of how these historic sites operate today. Its both carefully researched and lyrical. I mean Smith is a poet and the sentences in this book just are piercingly alive. And it’s both extremely personal—it is the author’s story—and extraordinarily sweeping. It amplifies lots of other voices. Past and present. Reading it I kept thinking about that great Alice Walker line ‘All History is Current’.”John Green, New York Times bestselling author of The Anthropocene Reviewed

-

“The summer’s most visionary work of nonfiction is this radical reckoning with slavery, as represented in the nation’s monuments, plantations, and landmarks.”Adrienne Westenfeld, Esquire

-

“The detail and depth of the storytelling is vivid and visceral, making history present and real. Equally commendable is the care and compassion shown to those Smith interviews — whether tour guides or fellow visitors in these many spaces. Due to his care as an interviewer, the responses Smith elicits are resonant and powerful. . . . Smith deftly connects the past, hiding in plain sight, with today's lingering effects.”Hope Wabuke, NPR

-

“This isn’t just a work of history, it’s an intimate, active exploration of how we’re still constructing and distorting our history.”Ron Charles, The Washington Post

-

“Both an honoring and an exposé of slavery’s legacy in America and how this nation is built upon the experiences, blood, sweat and tears of the formerly enslaved.”The Root

-

“What [Smith] does, quite successfully, is show that we whitewash our history at our own risk. That history is literally still here, taking up acres of space, memorializing the past, and teaching us how we got to be where we are, and the way we are. Bury it now and it will only come calling later."USA Today

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use