Promotion

25% off sitewide. Make sure to order by 11:59am, 12/12 for holiday delivery! Code BEST25 automatically applied at checkout!

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

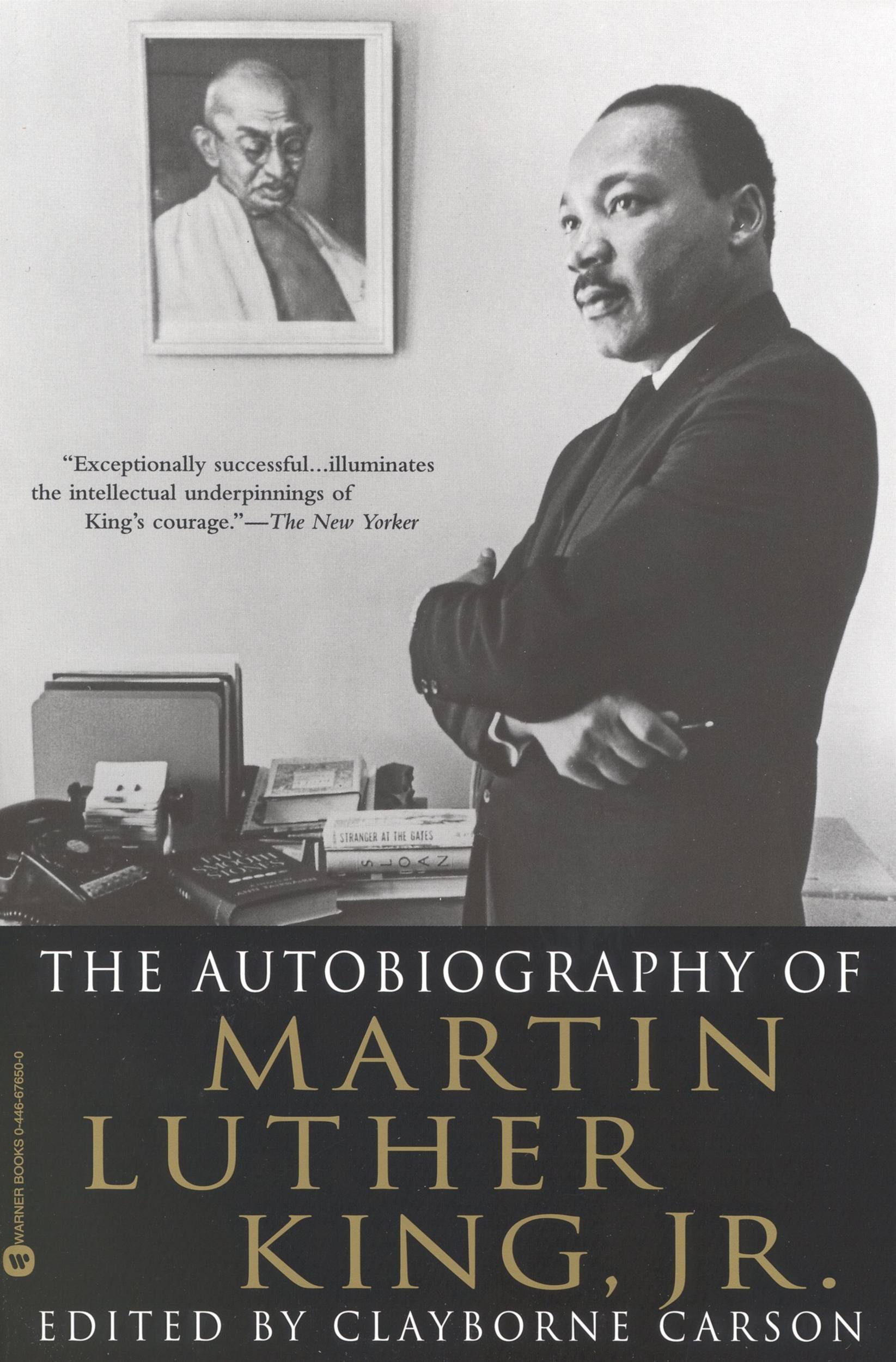

The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jan 1, 2001

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780759520370

Price

$10.99Price

$13.99 CADFormat

Format:

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around January 1, 2001. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

Martin Luther King: the child and student who rebelled against segregation. The dedicated minister who questioned the depths of his faith and the limits of his wisdom. The loving husband and father who sought to balance his family’s needs with those of a growing, nationwide movement. And to most of us today, the world-famous leader who was fired by a vision of equality for people everywhere.

Relevant and insightful, The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. offers King’s seldom disclosed views on some of the world’s greatest and most controversial figures: John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, Lyndon B. Johnson, Mahatma Gandhi, and Richard Nixon. It paints a moving portrait of a people, a time, and a nation in the face of powerful change. And it shows how Americans from all walks of life can make a difference if they have the courage to hope for a better future.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use