By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

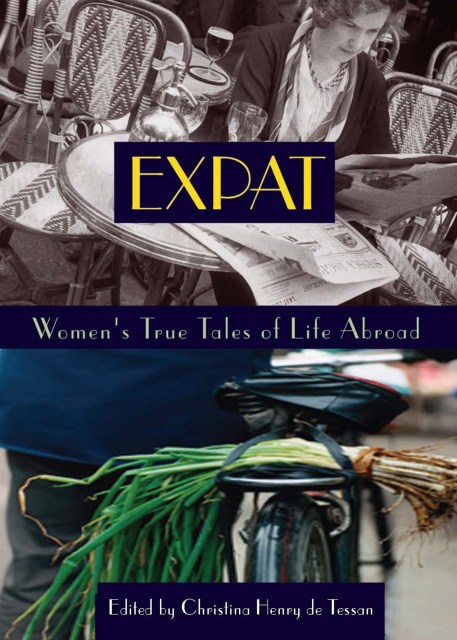

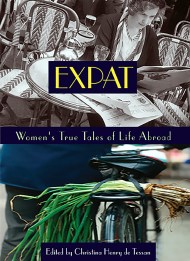

Expat

Women's True Tales of Life Abroad

Contributors

Edited by Christina Henry de Tessan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Mar 5, 2013

- Page Count

- 320 pages

- Publisher

- Seal Press

- ISBN-13

- 9781580055208

Price

$11.99Price

$15.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 5, 2013. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

It's one thing to travel abroad—to stay in charming hotels and deliberate over whether to visit this museum or relax at that café even to head off the beaten track for a glimpse of "real" life—and another thing altogether to move to another country. Expat chronicles the experiences of twenty-two ordinary women living extraordinary lives in outposts as far flung as Borneo, Ukraine, India, Greece, Brazil, China and the Czech Republic.

In vivid detail, these writers share how the realities of life abroad match up to the expat fantasy. One woman negotiates the rough courtesies of Serbia, finding lives limned by harshness and an insurmountable spirit. Another is tutored on English manners by an eclectic bunch from Liverpool: "The cardinal sin in America is to be insincere, whereas the cardinal sin in England is to be boring." For some, their new home prompts them to reconnect or confront lost parts of themselves: One woman rediscovers her Judaism—in Japan; another writer's Western outlook is challenged by Javanese mysticism.

Many share their own naíve blunders and private confessions: a Thanksgiving dinner that doesn't translate in Paris, a sudden yearning for bad Hollywood films. And all discover that what it means to be "American" is redefined, again and again. taps into the bewilderment, the joys and surprises of life overseas, where the challenges often take unexpected forms and the obstacles overcome are all the more triumphant.

Featuring an astonishing range of perspectives, destinations and circumstances, this collection offers a beautiful portrait of expatriate life.

Genre:

Series:

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use