By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

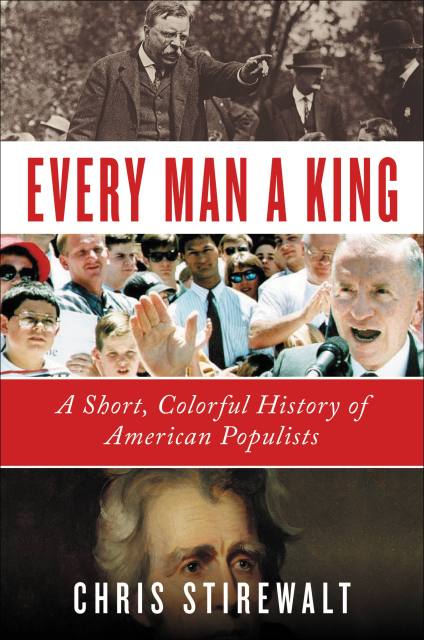

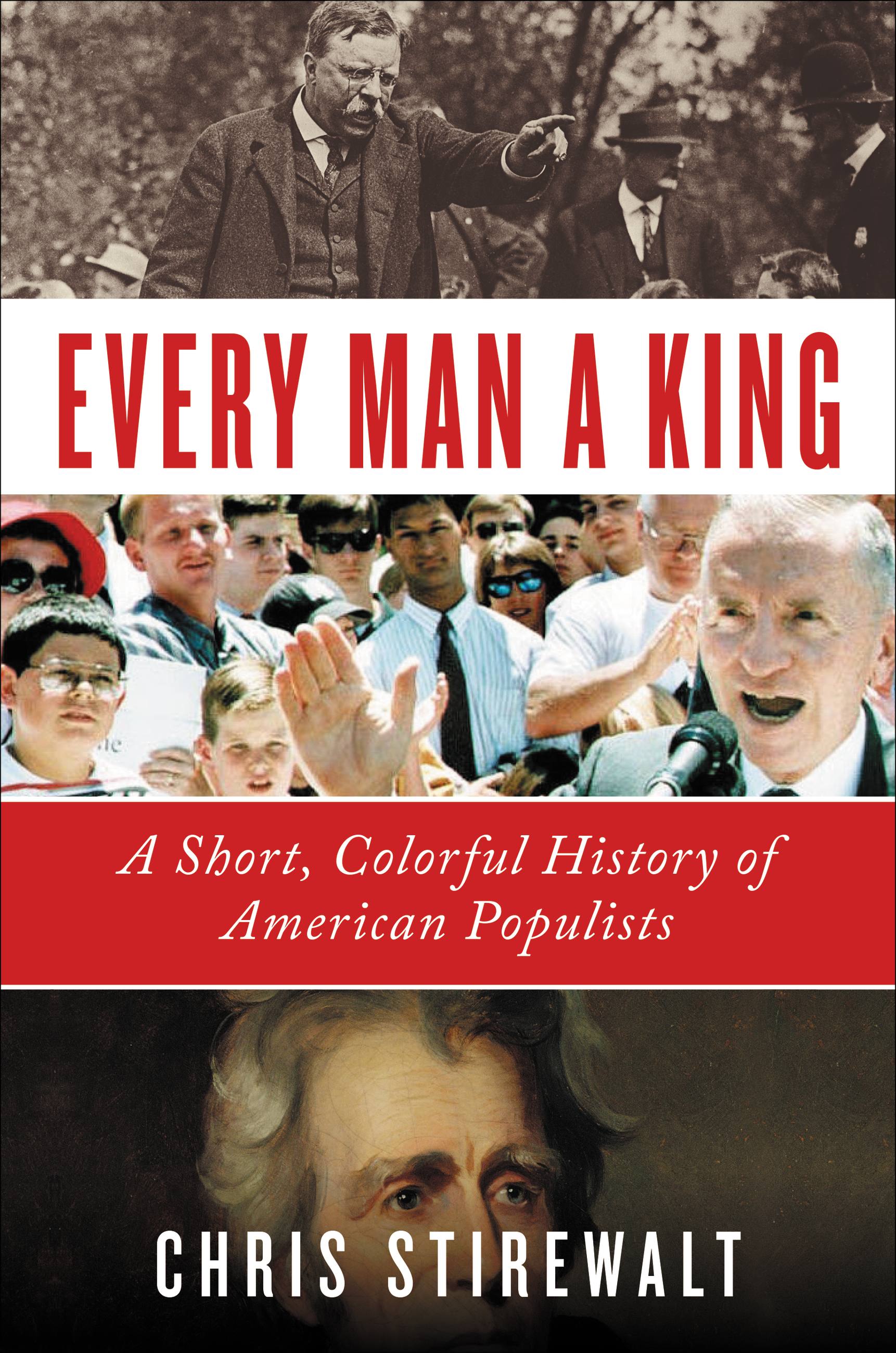

Every Man a King

A Short, Colorful History of American Populists

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 11, 2018

- Page Count

- 224 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538729793

Price

$14.99Price

$19.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $14.99 $19.99 CAD

- Hardcover $28.00 $36.50 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 11, 2018. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From Fox News‘ politics editor Chris Stirewalt — a fun and lively account of America’s populist tradition, from Andrew Jackson and Teddy Roosevelt, to Ross Perot, Pat Buchanan, and Donald Trump.

Whatever the ideological fad of the moment, American populism has always been home to a fascinating assortment of charismatic leaders, characters, kooks, cranks, and sometimes charlatans who have – with widely varying degrees of success – led the charge of ordinary folks who have gotten wise to the ways of the swamp. This attitude of skeptical resentment also makes populism a fertile field for the work of conspiracy theorists and other enthusiastic apostates from civic convention. After all, if the people in power are found to be rigging one part of the system, why not the rest? Every Man a King tells the stories of America’s populist leaders, from an elderly Andrew Jackson brutally caning his would-be-assassin, to William Jennings Bryan’s pre-speech routine that combined equally prodigious quantities of prayer and food, to Ross Perot’s military-style campaign that made even volunteers wear badges with stars to show rank. It is a rollicking history of an American attitude that has shaped not only our current moment, but also the long struggle over who gets to define the truths we hold to be self evident.

Whatever the ideological fad of the moment, American populism has always been home to a fascinating assortment of charismatic leaders, characters, kooks, cranks, and sometimes charlatans who have – with widely varying degrees of success – led the charge of ordinary folks who have gotten wise to the ways of the swamp. This attitude of skeptical resentment also makes populism a fertile field for the work of conspiracy theorists and other enthusiastic apostates from civic convention. After all, if the people in power are found to be rigging one part of the system, why not the rest? Every Man a King tells the stories of America’s populist leaders, from an elderly Andrew Jackson brutally caning his would-be-assassin, to William Jennings Bryan’s pre-speech routine that combined equally prodigious quantities of prayer and food, to Ross Perot’s military-style campaign that made even volunteers wear badges with stars to show rank. It is a rollicking history of an American attitude that has shaped not only our current moment, but also the long struggle over who gets to define the truths we hold to be self evident.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use