Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

American Psychosis

A Historical Investigation of How the Republican Party Went Crazy

Contributors

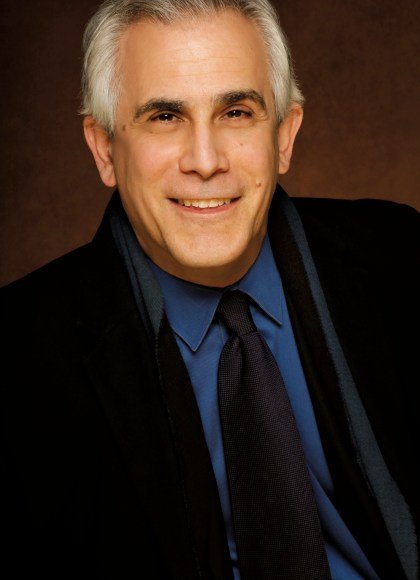

By David Corn

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 12, 2023

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Twelve

- ISBN-13

- 9781538723067

Price

$19.99Price

$24.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $24.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $38.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 12, 2023. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

#1 New York Times bestselling author and investigative reporter David Corn tells the wild and harrowing story of the Republican Party’s decades-long relationship with far-right extremism, bigotry, and paranoia.

A fast-paced, rollicking, behind-the-scenes account of how the GOP since the 1950s has encouraged and exploited extremism, bigotry, and paranoia to gain power, American Psychosis offers readers a brisk, can-you-believe-it journey through the netherworld of far-right irrationality and the Republican Party’s interactions with the darkest forces in America. In a compelling and thoroughly-researched narrative, Corn reveals the hidden history of how the Party of Lincoln forged alliances with extremists, kooks, racists, and conspiracy-mongers and fostered fear, anger, and resentment to win elections—and how this led to Donald Trump’s triumph and the transformation of the GOP into a Trump personality cult that foments and bolsters the crazy and dangerous excesses of the right.

The Trump-incited insurrectionist attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021, was no aberration. American Psychosis shows it was a continuation of the long and deep-rooted Republican practice of boosting and weaponizing the rage and derangement of the right.

The gripping tale in American Psychosis covers the last seven decades. From McCarthyism to the John Birch Society to segregationists to the New Right to the religious right to Rush Limbaugh to Newt Gingrich to the militia movement to Fox News to Sarah Palin to the Tea Party to Trumpism, the Republican Party has deliberately nurtured and exploited rightwing fear and loathing fueled by paranoia, grievance, and tribalism. This powerful and important account explains how one political party has harnessed the worst elements in politics to poison the nation’s discourse and threaten American democracy.

“[Corn is] a great journalist. I love the way he thinks. I love the way he writes. I’m so glad he’s done a super-readable, modern history of the right…We just need smart, digestible history about this stuff right now…[American Psychosis] is perfectly timed…Relevant history for where we are right now.” —Rachel Maddow, host, The Rachel Maddow Show

“With American Psychosis, David Corn ‘did the full homework to take us all the way back to where it really begins.’” —Lawrence O’Donnell, host, The Last Word

-

“David Corn’s AMERICAN PSYCHOSIS is essential reading for anyone hoping to restore political sanity in America. He argues convincingly that the toxic brew of bigotry, conspiracy theories, and lies that define Trumpism started long before Trump. Corn chronicles the Republican Party’s decades-long slide into the gutter and weaves this investigative history into a compelling narrative that is equal parts horrifying and entertaining. Corn has managed to make brilliant sense of American senselessness.”Jane Mayer, author of Dark Money

-

“In this searing and deeply reported work, Corn recounts how the modern GOP succumbed to the extremism, alternative realities, and paranoia that spread the ‘American psychosis’ that exploded on January 6. A desperately important read.”Charlie Sykes, author of How The Right Lost Its Mind

-

“David Corn makes the powerful case that Donald Trump didn’t come out of nowhere. He expertly traces the antecedents of Trump and Trumpism over the decades. This is a must-read if you want to understand what brought us to Trump and why the GOP remains a threat to American democracy.”Jennifer Rubin, columnist, the Washington Post

-

“AMERICAN PSYCHOSIS requires us to revisit the dark forces that have shaped our government and charges us to safeguard American democracy from those who inflame our worst instincts to destroy it.”Heather Cox Richardson, professor of history, Boston College

-

“The hatred, bigotry, conspiracism, paranoia, and rage inside the GOP didn’t start with Donald Trump. In this important and convincing account, David Corn shows that such poison has been in the marrow of the Republican Party for more than seventy years.”Jonathan Alter, author of The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies

-

"AMERICAN PSYCHOSIS is a brave and important book, written by one of the sharpest political writers of our time."Molly Jong-Fast, contributing writer, The Atlantic

-

"The genesis from a conventional party to a fanatic cult did not start with Donald Trump. The roots go much deeper and much further back. David Corn, with rich detail and in compelling prose, gives us a full history of the journey to crazy. Whether you have read a lot about the Republican Party or are just beginning to examine how the country could have come to this deeply dangerous point, AMERICAN PSYCHOSIS is a must read."Norman Ornstein, Emeritus Scholar, The American Enterprise Institute

-

"David Corn was at the forefront of journalism in detailing the corruption and danger of the Trump campaign and the Trump Presidency. Now, he has taken a highly useful long look back at the far right's role in Republican politics over the decades. Trump and Trumpism did not come from nowhere. There is a long back story. Corn tells it here, bringing to history the verve and energy he brings to all of his reporting."E. J. Dionne Jr., author, Why the Right Went Wrong

-

"The veteran political journalist connects the authoritarianism and White supremacism of yore with the Trumpism of today... It’s a zigzag line indeed, but Corn makes important connections. ...A sobering look at the ideological destruction, born of cynicism and opportunism, of a once-principled party.”Kirkus Reviews

-

"David Corn’s new book chronicles how Republicans themselves made the MAGA Monster that now devours their party. Every modern Republican, Trump supporter or not, has been complicit in this nightmare"Elie Mystal, correspondent, The Nation

-

"[Corn is] a great journalist. I love the way he thinks. I love the way he writes. I'm so glad he's done a super-readable, modern history of the right...We just need smart, digestible history about this stuff right now...[AMERICAN PSYCHOSIS] is perfectly timed...Relevant history for where we are right now."Rachel Maddow, host, The Rachel Maddow Show

-

"With AMERICAN PSYCHOSIS, David Corn 'did the full homework to take us all the way back to where it really begins.'"Lawrence O'Donnell, host, The Last Word

-

"David Corn “documents in this colorful and persuasive treatise ‘the Republican Party’s decades-long relationship with extremism.’…[Corn] draws a clear through line from the rise of Barry Goldwater to the January 6, 2021, Capitol riot….[I]ncisive political history.”Publisher's Weekly