Promotion

Use code SPRING26 for 20% off sitewide.

By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

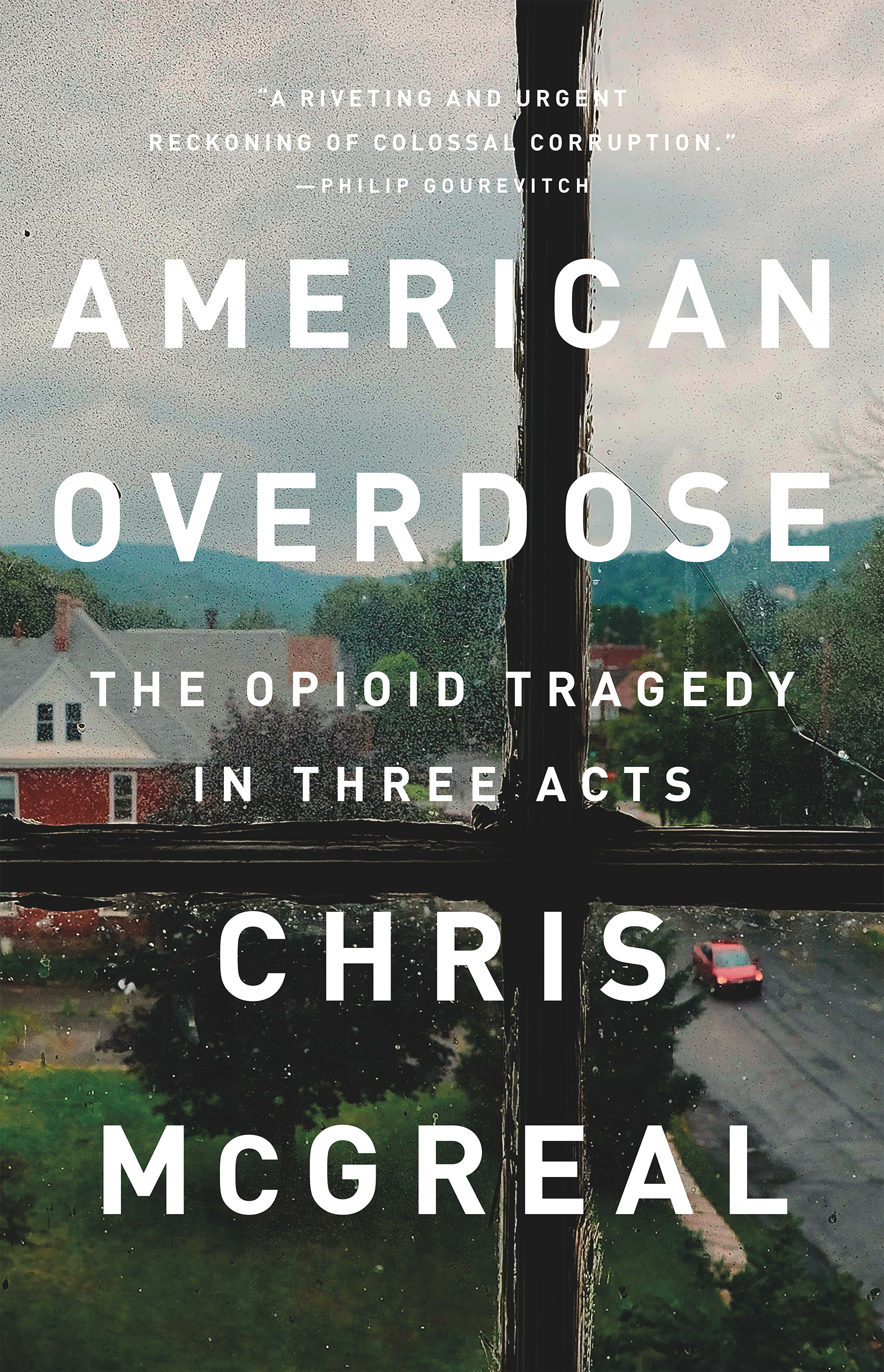

American Overdose

The Opioid Tragedy in Three Acts

Contributors

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 24, 2019

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- PublicAffairs

- ISBN-13

- 9781541742758

Price

$17.99Price

$22.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $17.99 $22.99 CAD

- ebook $11.99 $15.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 24, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The opioid epidemic has been described as “one of the greatest mistakes of modern medicine.” But calling it a mistake is a generous rewriting of the history of greed, corruption, and indifference that pushed the US into consuming more than 80 percent of the world’s opioid painkillers.

Journeying through lives and communities wrecked by the epidemic, Chris McGreal reveals not only how Big Pharma hooked Americans on powerfully addictive drugs, but the corrupting of medicine and public institutions that let the opioid makers get away with it.

The starting point for McGreal’s deeply reported investigation is the miners promised that opioid painkillers would restore their wrecked bodies, but who became targets of “drug dealers in white coats.”

A few heroic physicians warned of impending disaster. But American Overdose exposes the powerful forces they were up against, including the pharmaceutical industry’s coopting of the Food and Drug Administration and Congress in the drive to push painkillers — resulting in the resurgence of heroin cartels in the American heartland. McGreal tells the story, in terms both broad and intimate, of people hit by a catastrophe they never saw coming. Years in the making, its ruinous consequences will stretch years into the future.

-

"American Overdoseconfirms Chris McGreal's stature as one of the truly essential reporters of our times. It is - in its investigative depth and documentary breadth - a riveting and urgent reckoning of colossal corruption that has taken such a staggering toll on twenty-first century American life."Philip Gourevitch, author of We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families

-

"In this gripping account, McGreal exposes the avarice and corruption that caused one of the most shocking crises in American history. A searing expose full of extraordinary characters - heroes, villains and victims."Katty Kay, contributor MSNBC Morning Joe, presenter BBC World News America

-

"McGreal shows how the overdose crisis was driven by the pursuit of profits, not just drugs-both of which combine our instinctive craving for pleasure with our evolving capacity for denial and deceit. Fascinating, disturbing, impressively researched and elegantly written."Marc Lewis, author of The Biology of Desire: Why Addiction is Not a Disease

-

"With great reporting and compelling storytelling, American Overdose lays bare the tragedy of the opioid epidemic tearing at the soul of the United States. Those who want to understand the issue of narcotics and addiction have to read it."Ioan Grillo, author of El Narco

-

"A deftly researched account of America's opioid epidemic. McGreal's book is authoritative in tone and vernacular in style....[A] powerful narrative."Kirkus Reviews, Starred Review

-

"This urgent, readable chronicle, which names names and pulls no punches, clearly and compassionately illuminates the evolution of America's mass addiction problem."Publishers Weekly, Starred Review

-

"McGreal, an award-winning journalist, presents this grim cautionary tale of opioids, greed, and addiction in three acts: 'Dealing,' 'Hooked,' and Withdrawal'.... McGreal goes on to successfully address the question of how the greatest drug epidemic in history grew largely unchecked for nearly two decades....What can be done to reverse this? McGreal's powerfully stated indictment is a start."Booklist, Starred Review

-

"Thorough, gripping and excellent."--The Straight Dope, Medium.com

-

"[A] powerful encapsulation of that epidemic....a timely examination of hard-won lessons."Nature

-

"Staggering... Zola-esque in its dark twists and turns."Ed Vulliamy, LiteraryReview

-

"[A] searing book... Appalachian accents and anger steam off the page."TheSunday Times

-

"Compelling.... reads like a white-collar The Wire, with a cast of characters determined to exact as much money as possible regardless of the human cost."The Observer

-

"An engaging, cogently argued book."Evening Standard

-

"Astonishing... McGreal's book is forensic in its detailing and turns up some eye-popping examples."Esquire UK

-

"McGreal provides a scorching exposé....Most important, American Overdose tells the story of institutional failure and corruption: among local officials, in federal agencies, the United States Congress, and the White House."Psychology Todayonline

-

"Vivid reporting... [McGreal] explains in horrifying detail how this vision of a pain-free America - pharmacologically unrealistic to begin with - was subverted by a greedy combination of pharmaceutical companies, drug distributors, doctors and pharmacists, aided and abetted by complacent regulators and politicians."Financial Times

-

"In American Overdose Chris McGreal of the Guardian looks unsparingly at the causes of the opioid crisis that kills tens of thousands of Americans a year."The Economist

-

"A fast, accessible read for those trying to come to terms with a national nightmare."Law & Crime

-

"An exposé that will have readers riveted from cover to cover."GreenBay Press Gazette

-

"[A] powerful account ... American Overdose is a tale of bad decision making, greed and malfeasance that is still unfolding, and not one about which we can afford to be complacent."Nick Hopkinson, British Medical Journal

-

"A detailed view of the corruption that enabled the spread of opiates to go unchecked by the healthcare industry, government or law enforcement."London Review ofBooks