By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

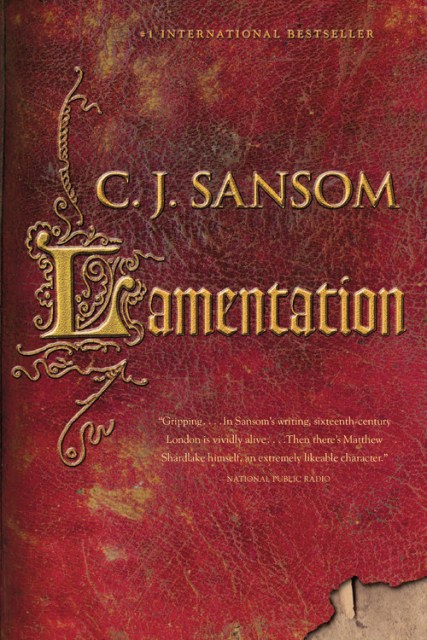

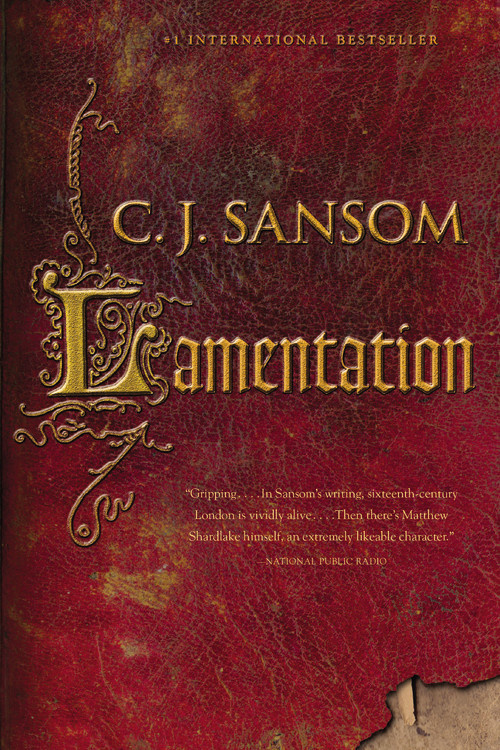

Lamentation

A Shardlake Novel

Contributors

By C.J. Sansom

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 2, 2016

- Page Count

- 672 pages

- Publisher

- Mulholland Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316254977

Price

$22.99Format

Format:

- Trade Paperback $22.99

- ebook $12.99

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 2, 2016. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

As Henry VIII lies on his deathbed, an incendiary manuscript threatens to tear his court apart in book six of the Shardlake series, now an original streaming series on Hulu.

Summer, 1546. King Henry VIII is slowly, painfully dying. His Protestant and Catholic councilors are engaged in a final and decisive power struggle; whoever wins will control the government. As heretics are hunted across London, and radical Protestants are burned at the stake, the Catholic party focuses its attack on Henry’s sixth wife — and Matthew Shardlake’s old mentor — Queen Catherine Parr.Shardlake, still haunted by his narrow escape from death the year before, steps into action when the beleaguered and desperate Queen summons him to Whitehall Palace to help her recover a dangerous manuscript. The Queen has authored a confessional book, Lamentation of a Sinner, so radically Protestant that if it came to the King’s attention it could bring both her and her sympathizers crashing down. Although the secret book was kept hidden inside a locked chest in the Queen’s private chamber, it has inexplicably vanished. Only one page has been recovered — clutched in the hand of a murdered London printer.

Shardlake’s investigations take him on a trail that begins among the backstreet printshops of London, but leads him and his trusty assistant Jack Barak into the dark and labyrinthine world of court politics, a world Shardlake swore never to enter again. In this crucible of power and ambition, Protestant friends can be as dangerous as Catholic enemies, and those with shifting allegiances can be the most dangerous of all.

-

PRAISE FOR C.J. SANSOM AND THE SHARDLAKE SERIES:Kate Atkinson

"C.J. Sansom has long been one of my favorite writers." -

"Among the most distinguished of modern historical novelists."P.D. James

-

"Sansom has an unerring sense of pace and a deft historical touch."The New Yorker

-

"Sansom brings alive all levels of English society, from cutthroats and common soldiers to the king and queen themselves."Washington Post

-

"A richly entertaining and scholarly series. History never seemed so real."New York Times Book Review

-

"Sansom seems to have born with, or instinctively acquired, that precious balance of creativity and research, history and humanity."Chicago Tribune

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use