Promotion

Use code MOM24 for 20% off site wide + free shipping over $45

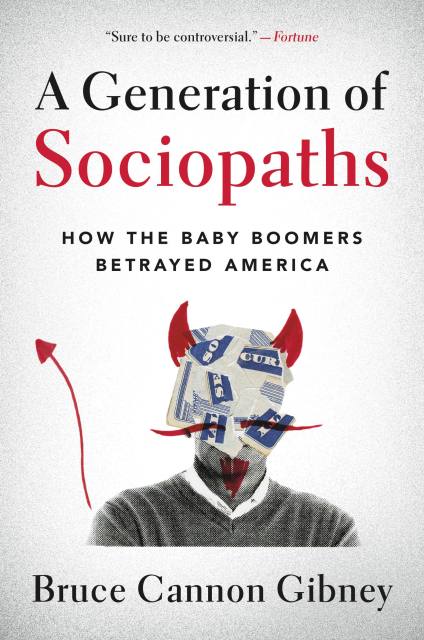

A Generation of Sociopaths

How the Baby Boomers Betrayed America

Contributors

Formats and Prices

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $24.99 $31.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around March 7, 2017. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Also available from:

In his “remarkable” (Men’s Journal) and “controversial” (Fortune) book — written in a “wry, amusing style” (The Guardian) — Bruce Cannon Gibney shows how America was hijacked by the Boomers, a generation whose reckless self-indulgence degraded the foundations of American prosperity.

In A Generation of Sociopaths, Gibney examines the disastrous policies of the most powerful generation in modern history, showing how the Boomers ruthlessly enriched themselves at the expense of future generations.

Acting without empathy, prudence, or respect for facts–acting, in other words, as sociopaths–the Boomers turned American dynamism into stagnation, inequality, and bipartisan fiasco. The Boomers have set a time bomb for the 2030s, when damage to Social Security, public finances, and the environment will become catastrophic and possibly irreversible–and when, not coincidentally, Boomers will be dying off.

Gibney argues that younger generations have a fleeting window to hold the Boomers accountable and begin restoring America.

In A Generation of Sociopaths, Gibney examines the disastrous policies of the most powerful generation in modern history, showing how the Boomers ruthlessly enriched themselves at the expense of future generations.

Acting without empathy, prudence, or respect for facts–acting, in other words, as sociopaths–the Boomers turned American dynamism into stagnation, inequality, and bipartisan fiasco. The Boomers have set a time bomb for the 2030s, when damage to Social Security, public finances, and the environment will become catastrophic and possibly irreversible–and when, not coincidentally, Boomers will be dying off.

Gibney argues that younger generations have a fleeting window to hold the Boomers accountable and begin restoring America.

Genre:

- On Sale

- Mar 7, 2017

- Page Count

- 464 pages

- Publisher

- Hachette Books

- ISBN-13

- 9780316395809

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use