By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

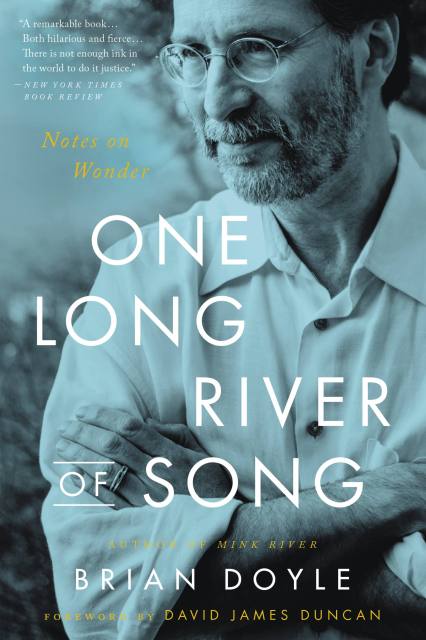

One Long River of Song

Notes on Wonder

Contributors

By Brian Doyle

Introduction by David James Duncan

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Dec 3, 2019

- Page Count

- 272 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316492874

Price

$12.99Price

$16.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $12.99 $16.99 CAD

- Hardcover $29.00 $38.00 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around December 3, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

From a "born storyteller" (Seattle Times), this playful and moving bestselling book of essays invites us into the miraculous and transcendent moments of everyday life.

When Brian Doyle passed away at the age of sixty after a bout with brain cancer, he left behind a cult-like following of devoted readers who regard his writing as one of the best-kept secrets of the twenty-first century. Doyle writes with a delightful sense of wonder about the sanctity of everyday things, and about love and connection in all their forms: spiritual love, brotherly love, romantic love, and even the love of a nine-foot sturgeon.

At a moment when the world can sometimes feel darker than ever, Doyle's writing, which constantly evokes the humor and even bliss that life affords, is a balm. His essays manage to find, again and again, exquisite beauty in the quotidian, whether it's the awe of a child the first time she hears a river, or a husband's whiskers that a grieving widow misses seeing in her sink every morning. Through Doyle's eyes, nothing is dull.

David James Duncan sums up Doyle's sensibilities best in his introduction to the collection: "Brian Doyle lived the pleasure of bearing daily witness to quiet glories hidden in people, places and creatures of little or no size, renown, or commercial value, and he brought inimitably playful or soaring or aching or heartfelt language to his tellings." A life's work, One Long River of Song invites readers to experience joy and wonder in ordinary moments that become, under Doyle's rapturous and exuberant gaze, extraordinary.

When Brian Doyle passed away at the age of sixty after a bout with brain cancer, he left behind a cult-like following of devoted readers who regard his writing as one of the best-kept secrets of the twenty-first century. Doyle writes with a delightful sense of wonder about the sanctity of everyday things, and about love and connection in all their forms: spiritual love, brotherly love, romantic love, and even the love of a nine-foot sturgeon.

At a moment when the world can sometimes feel darker than ever, Doyle's writing, which constantly evokes the humor and even bliss that life affords, is a balm. His essays manage to find, again and again, exquisite beauty in the quotidian, whether it's the awe of a child the first time she hears a river, or a husband's whiskers that a grieving widow misses seeing in her sink every morning. Through Doyle's eyes, nothing is dull.

David James Duncan sums up Doyle's sensibilities best in his introduction to the collection: "Brian Doyle lived the pleasure of bearing daily witness to quiet glories hidden in people, places and creatures of little or no size, renown, or commercial value, and he brought inimitably playful or soaring or aching or heartfelt language to his tellings." A life's work, One Long River of Song invites readers to experience joy and wonder in ordinary moments that become, under Doyle's rapturous and exuberant gaze, extraordinary.

Genre:

-

"Astonishing... gorgeous... Doyle was a writer 'made of love and song and amusement.' Every living thing intrigued him and was worthy of his powerful capacity for study and his equally powerful capacity for celebration."Margaret Renkl, New York Times

-

"Brian Doyle took on the everyday and he suffused it, every last drop of it, with a redefining soulfulness... This posthumous collection will leave you marveling and wiping away the occasional tear. Certainly you will spill ink on its pages---starring and underlining, sprinkling exclamations up and down the margins... Over and over, Doyle's musings are canticles of joy, punctuated with occasional double-shots of heartbreak and humility. It's the textured layering, the leap from shadow to light, that keeps the reader alert, and ever absorbing. Always, emphatically, there comes wisdom; it's a signature move, one you can count on. Have your pens aimed and ready. It's a gospel of the ordinary, the shoved-aside, the otherwise overlooked. And at the heart of it, that ineffable and necessary unction, a holiness you can all but hold in your palms."Barbara Mahany, Chicago Tribune

-

"A final collection of Doyle's lyrical, sometimes mystical pieces about life and its gifts. Doyle often used his Catholicism to explore the human and natural worlds, but this is perhaps the most generous, universal 'religious writing' you'll ever read."Bethanne Patrick, Washington Post

-

"Both ecstatic and sober...This posthumous collection dances on the edge of mortality, tossing out exaltations and questions, and offering a fresh, playful, slant on spiritual writing...a celebration of life, love, and waking each day."Jane Ciabattari, BBC

-

"The first pleasure of reading Doyle lies in being swept away by the deft melding of his two most distinctive qualities, his sentences and his sensibility. How he loved sentences. And how he loved the world. Form and content never fit more hand in glove...I don't know a writer who more reliably or with such seeming ease plucks genuine epiphanies fresh from the ether. The ubiquity of these is testament to Doyle's craft or, perhaps, the quality of his attention...One Long River of Song demonstrates what Doyle's writing has always demonstrated, that when you find the courage to pay attention and be open to love, you can trust that 'doing your chosen work with creativity and diligence will shiver people far beyond your ken.'"Scott F. Parker, The Oregonian

-

"A wonder-filled book... Doyle's essays often wriggle with wild miracles... Doyle's greatest gift may be the quiet wisdom that grows out of his senses of humor and humility and gratitude... Reading this collection of essays will awaken readers to the everyday wonders of saying yes."Tom Montgomery Fate, The Christian Century

-

"Brian's glowing essays create a vision of what a good person might be, what a good life surely is, a larger story of the transformative power of joyful gratitude."Kathleen Dean Moore, Orion Magazine

-

"One Long River of Song celebrates life in all its iterations. Remarkable for their kindness and intelligence, their humanity and humor, these essays are a thoughtful antidote for the cheap cynicism present in so much of the media we consume."Ann Cannon, Salt Lake Tribune

-

"The essays in One Long River of Song are truly staggering--as close as stones in our palms, and as vast as the sky. Brian Doyle's voice is full of tender pivots, keen wit, and startling joy, summoning all of us to pay more passionate attention to the world."Leslie Jamison, author of the New York Times bestsellers TheEmpathy Exams and The Recovering

-

"A posthumous collection of stunning mystical prose...Doyle's prose is so expansive and dripping with visceral detail that even the briefest vignettes are often a wondrous adventure. This brilliant compendium of spiritual musings will resonate with people of any faith--or of none."Kirkus (starred review)

-

"A generous, posthumous collection [with] the rhythm of poems and the lyricism of songs...infused with qualities of spirit, goodness, and grace. Doyle was a wonderful stylist...he is generous, almost profligate in filling his work with [love]...readers will be equally grateful for this lovely book and its beautiful contents."Michael Cart, Booklist (starred review)

-

"An excellent, thought-provoking collection of essays that is likely to make you run out and pick up anything else he's written."Ray Walsh, Lansing State Journal

-

"Doyle's curiosity is insatiable and his self-described Celtic-mystic disposition spots the transcendent regularly. As much haunted by the language of James Joyce as the lessons of Jesus, Doyle sees and celebrates what happens every day in each essay of this eclectic collection. This 'best-of' should enlarge his circle of admirers."Publishers Weekly

-

"Dazzling... Doyle's writing bursts with vivid descriptions...a renewed opportunity for more readers to discover the insight and humanity of his work...Doyle's brand of theology will appeal to fans of the work of writers like Anne Lamott...readers fortunate enough to discover the many pleasures of Brian Doyle's work here will be grateful, too, for that encounter."Harvey Freedenberg, Shelf Awareness

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use