By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

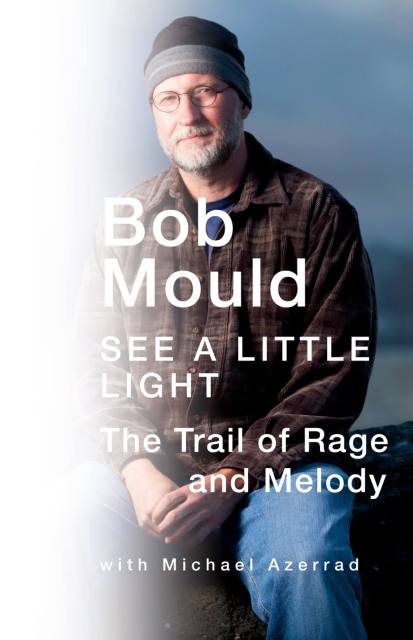

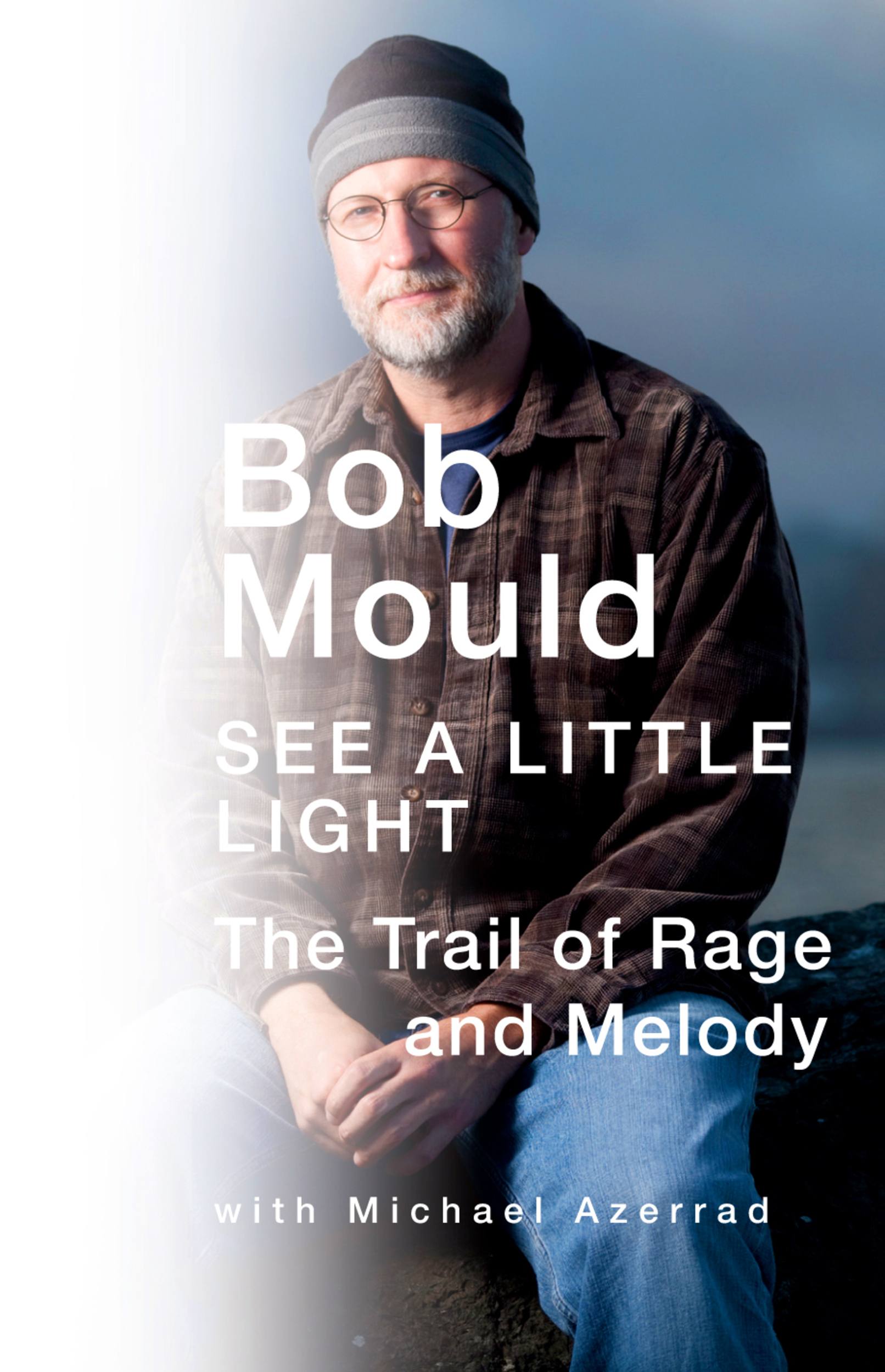

See a Little Light

The Trail of Rage and Melody

Contributors

By Bob Mould

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Jun 15, 2011

- Page Count

- 416 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown and Company

- ISBN-13

- 9780316175715

Price

$8.99Price

$11.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $8.99 $11.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged)

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around June 15, 2011. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

The long-awaited, full-force autobiography of American punk music hero, Bob Mould.

Bob Mould stormed into America’s punk rock scene in 1979, when clubs across the country were filling with kids dressed in black leather and torn denim, packing in to see bands like the Ramones, Black Flag, and the Dead Kennedys. Hardcore punk was a riot of jackhammer rhythms, blistering tempos, and bottomless aggression. And at its center, a new band out of Minnesota called Hvºsker Dvº was bashing out songs and touring the country on no money, driven by the inspiration of guitarist and vocalist Bob Mould. Their music roused a generation.

From the start, Mould wanted to make Hüsker Dü the greatest band in the world – faster and louder than the hardcore standard, but with melody and emotional depth. In See a Little Light, Mould finally tells the story of how the anger and passion of the early hardcore scene blended with his own formidable musicianship and irrepressible drive to produce some of the most important and influential music of the late 20th century.

For the first time, Mould tells his dramatic story, opening up to describe life inside that furnace and beyond. Revealing the struggles with his own homosexuality, the complexities of his intimate relationships, as well as his own drug and alcohol addiction, Mould takes us on a whirlwind ride through achieving sobriety, his acclaimed solo career, creating the hit band Sugar, a surprising detour into the world of pro wrestling, and most of all, finally finding his place in the world.

A classic story of individualism and persistence, Mould’s autobiography is an open account of the rich history of one of the most revered figures of punk, whose driving force altered the shape of American music.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use