By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

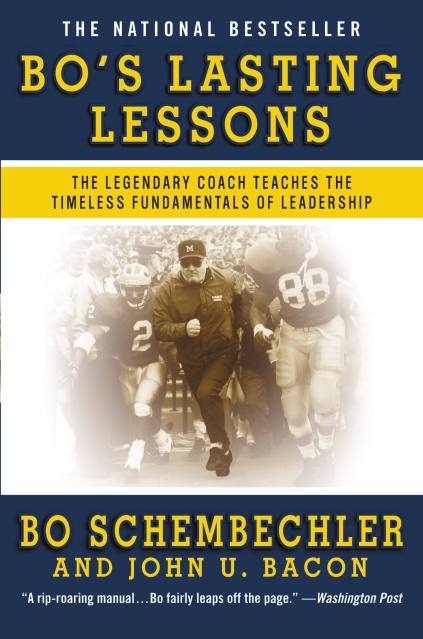

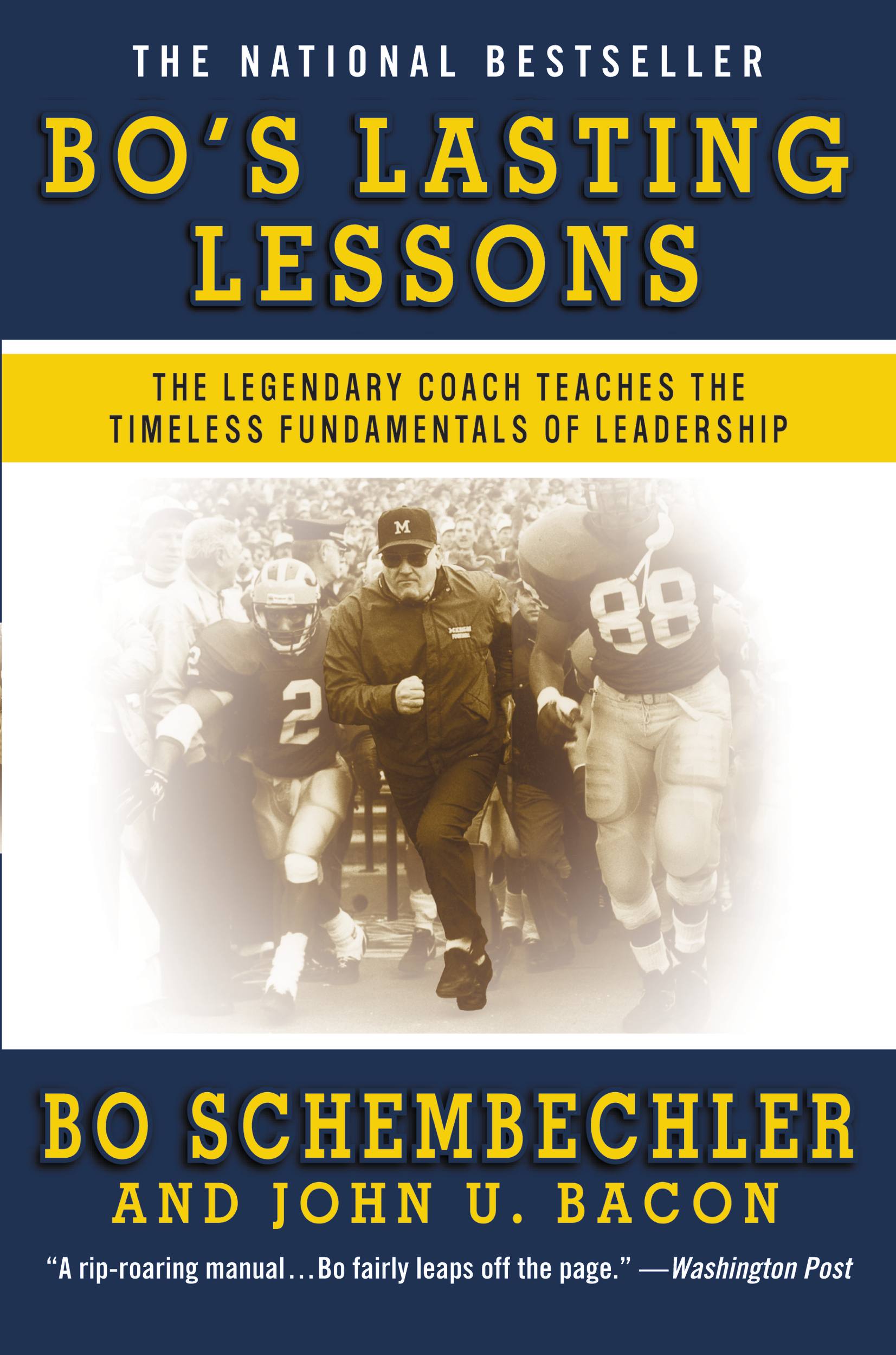

Bo’s Lasting Lessons

The Legendary Coach Teaches the Timeless Fundamentals of Leadership

Contributors

By John Bacon

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Sep 10, 2007

- Page Count

- 352 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780446402545

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Abridged)

- Trade Paperback $19.99 $25.99 CAD

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around September 10, 2007. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

There are very few coaches held higher esteem than Bo Schembechler. As coach of the University of Michigan football team, he won 13 Big Ten titles and finished as the winningest coach in their storied history. But beyond the wins and losses, Bo is best remembered for the remarkable impact he had on his players and fans alike.

In Bo’s Lasting Lessons, the coach draws on his years of experience, using first-person anecdotes to deliver timeless lessons on leadership, motivation and responsibility. His distinctive gruff voice leaps from the page.

With pithy language, Bo explains that true leadership requires the compassion to actively listen to your people, and then to have the courage to do what is right every time.

A big believer in peer pressure and in always making his players accountable for their actions, Schembechler has coached athletes who went on to become professional football players, doctors, lawyers and CEOs.

In Bo’s Lasting Lessons, the coach draws on his years of experience, using first-person anecdotes to deliver timeless lessons on leadership, motivation and responsibility. His distinctive gruff voice leaps from the page.

With pithy language, Bo explains that true leadership requires the compassion to actively listen to your people, and then to have the courage to do what is right every time.

A big believer in peer pressure and in always making his players accountable for their actions, Schembechler has coached athletes who went on to become professional football players, doctors, lawyers and CEOs.

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use