By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

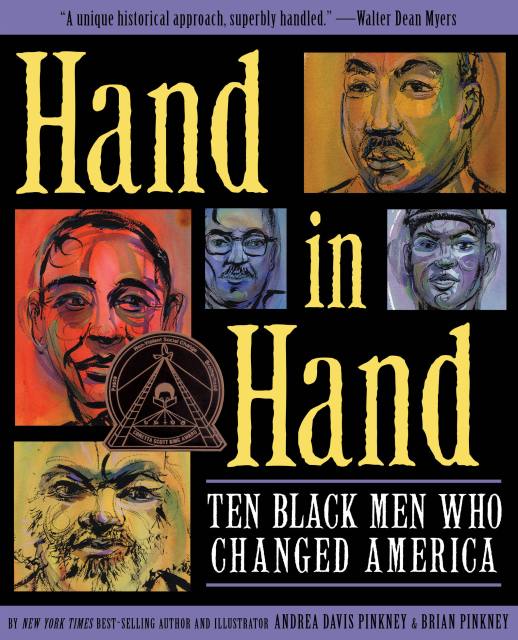

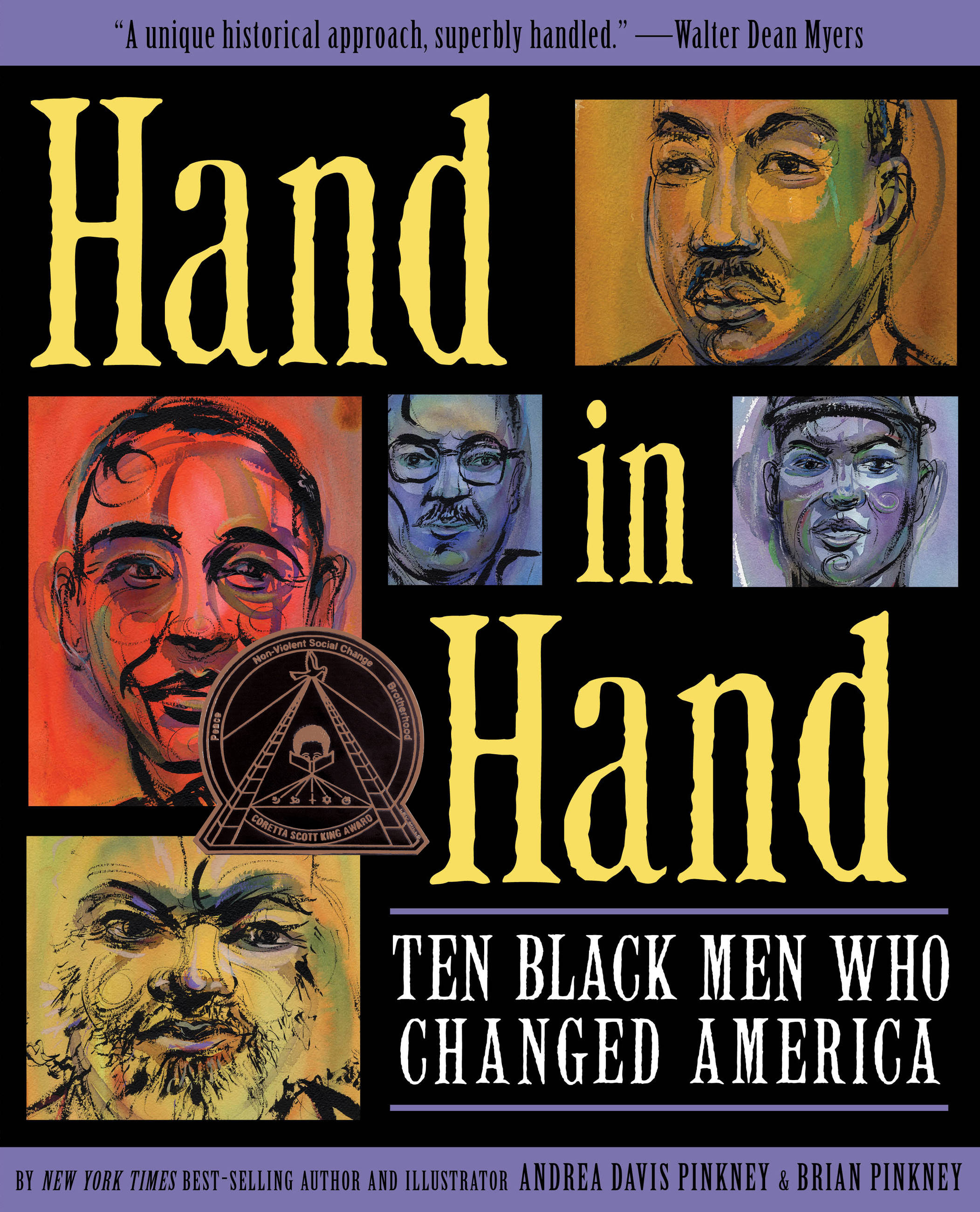

Hand in Hand

Ten Black Men Who Changed America (Coretta Scott King Author Award Winner)

Contributors

Illustrated by Brian Pinkney

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Nov 6, 2012

- Page Count

- 256 pages

- Publisher

- Little, Brown Books for Young Readers

- ISBN-13

- 9781423183037

Price

$9.99Price

$12.99 CADFormat

Format:

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Hardcover $25.99 $34.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $24.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around November 6, 2012. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

In this New York Times Notable Children's Book and winner of the Coretta Scott King Author Award, follow the life stories of ten Black men in American history and the legacies they left that forever changed the country.

Hand in Hand presents the stories of ten men from different eras in American history, organized chronologically to provide a scope from slavery to the modern day. The stories are accessible, fully-drawn narratives offering the subjects' childhood influences, the time and place in which they lived, their accomplishments and motivations, and the legacies they left for future generations as links in the "freedom chain." This book will be the definitive family volume on the subject, punctuated with dynamic full color portraits and spot illustrations by two-time Caldecott Honor winner and multiple Coretta Scott King Book Award recipient Brian Pinkney. Backmatter includes a civil rights timeline, sources, and further reading.

Profiled:

- Benjamin Banneker

- Frederick Douglass

- Booker T. Washington

- W.E.B. DuBois

- A. Philip Randolph

- Thurgood Marshall

- Jackie Robinson

- Malcolm X

- Martin Luther King, Jr

- Barack H. Obama II

-

"A unique historical approach, superbly handled."Walter Dean Myers

-

"[The] stories in this beautifully written book are equally fascinating, and entire volume is movingly enhanced by poetry and by the inviting, creative illustrations of Brian Pinkney."New York Times

-

"The inviting narrative and eloquent portrayal of these iconic men and the times in which they lived make for memorable reading."Publishers Weekly (starred review)

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use