By clicking “Accept,” you agree to the use of cookies and similar technologies on your device as set forth in our Cookie Policy and our Privacy Policy. Please note that certain cookies are essential for this website to function properly and do not require user consent to be deployed.

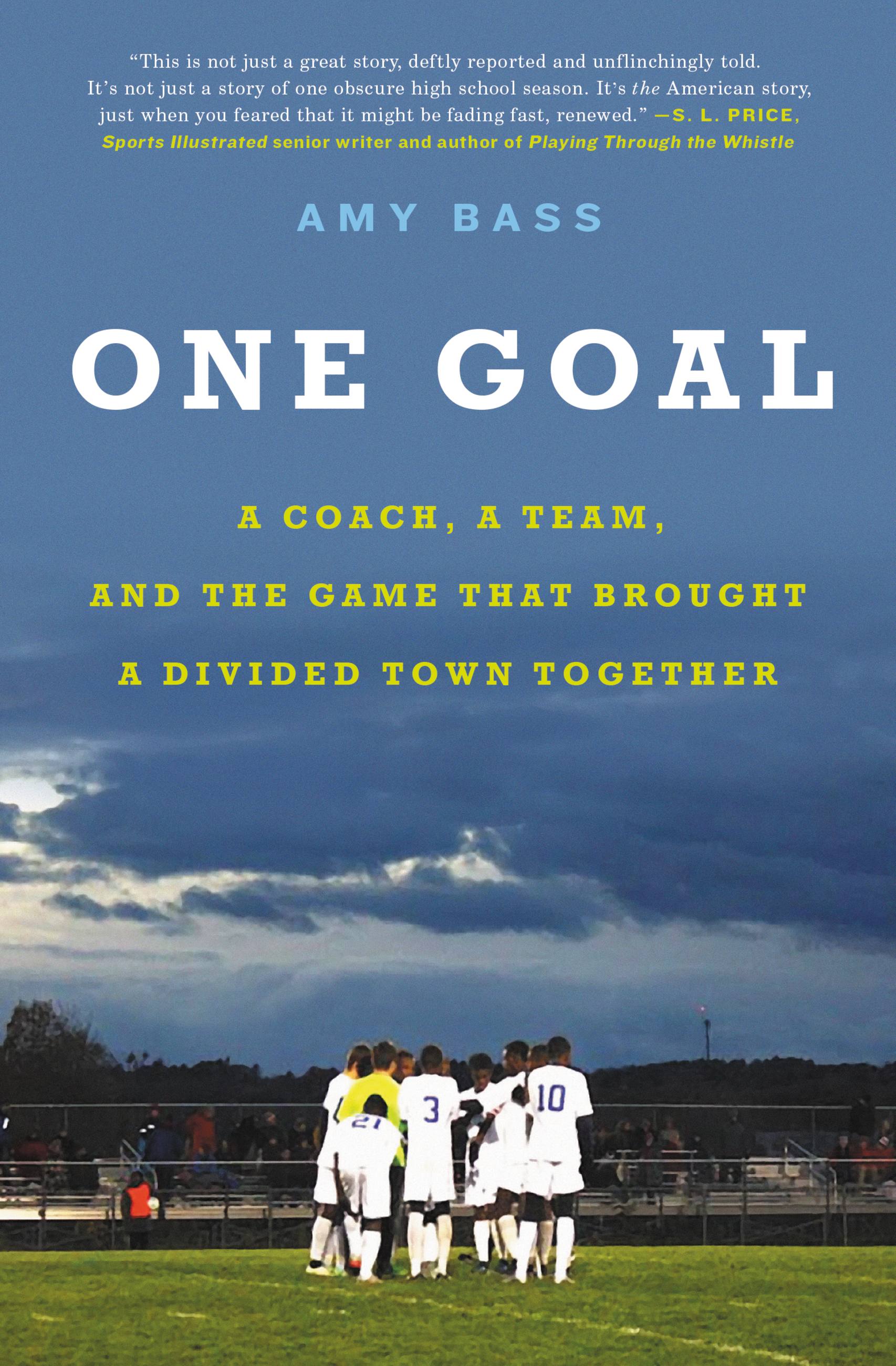

One Goal

A Coach, a Team, and the Game That Brought a Divided Town Together

Contributors

By Amy Bass

Formats and Prices

- On Sale

- Feb 26, 2019

- Page Count

- 336 pages

- Publisher

- Grand Central Publishing

- ISBN-13

- 9780316396554

Price

$21.99Price

$28.99 CADFormat

Format:

- Trade Paperback $21.99 $28.99 CAD

- ebook $9.99 $12.99 CAD

- Audiobook Download (Unabridged) $27.99

This item is a preorder. Your payment method will be charged immediately, and the product is expected to ship on or around February 26, 2019. This date is subject to change due to shipping delays beyond our control.

Buy from Other Retailers:

When thousands of Somali refugees resettled in Lewiston, Maine, a struggling, overwhelmingly white town, longtime residents grew uneasy. Then the mayor wrote a letter asking Somalis to stop coming, which became a national story. While scandal threatened to subsume the town, its high school’s soccer coach integrated Somali kids onto his team, and their passion began to heal old wounds. Taking readers behind the tumult of this controversial team — and onto the pitch where the teammates vied to become state champions and achieved a vital sense of understanding — One Goal is a timely story about overcoming the prejudices that divide us.

-

"The perfect parable for our time."Jane Leavy, The Wall Street Journal

-

"A magnificent and significant book about soccer in the United States...at once a stark look at the lives of the Somali refugees and a serious study of why soccer matters as a link between disparate cultures and peoples....Some of the vignettes of life for these refugees are as unforgettable as any heart-stopping game."The Globe & Mail

-

"Amy Bass tells a story that encompasses many of the things people love about sports, but also epitomizes many of the reasons sports matter."Bob Costas

-

"In this noisy era of glib hot-takes and childish finger-pointing, it's too easy to forget that the national character--hardworking, immigrant-fueled, optimistic--was built from the bottom up. Let Amy Bass remind you. Let her take you to our frosty upper righthand corner, to Lewiston, Maine, where quiet heroes like Mike McGraw, Abdi H. and the magical Blue Devils show again just how it's done. This is not just a great story, deftly reported and unflinchingly told. It's not just a story of one obscure high school season. It's the American story, just when you feared that it might be fading fast, renewed."S.L. Price, Sports Illustrated Senior Writer and author of PlayingThrough The Whistle: Steel, Football and an American Town

-

"A lively, informative, and entertaining...underdog story that skillfully blends elements of human compassion, passion for a sport, determination, and endurance with overtones of societal pressure and racism. It's an exhilarating narrative that shows how perseverance and the ability to disregard the narrow-mindedness of xenophobia can lead to victory....An edifying and adrenaline-charged tale."Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

-

"At a time when America seems consumed by divisiveness and hate, along comes One Goal, a beautiful and important reminder that humanity's strength is its togetherness. Yes, on the surface this is a soccer book. But Amy Bass' work is so much more. It's about overcoming odds, about embracing differences, about the triumph of will and spirit. A true gem of a book."Jeff Pearlman, New York Times bestselling author of The Bad Guys Won and Gunslinger

-

"A story that is not only relevant to our national discourse, but essential. This is a book about the big 'isms,' but it is most of all a book about human beings, compellingly and movingly rendered."Jeremy Schaap, New York Times bestselling author of Cinderella Man

-

"A touching work showing how different groups can come together through sports"Library Journal, Best Books of the Year

-

"In this gripping account of Lewiston's journey to its first-ever high-school soccer state championship, history professor Bass vividly tells the stories of the Somalis and Lewiston, exploring the resistance and racism the refugees faced in town and on the field....a heartening example of sport's ability to bring people together...Engrossing and informative."Booklist

-

"One Goal has made me feel optimistic about the country I live in. The vibrant, colorful and courageous characters will make you smile. The coach of the Blue Devils, Mike McGraw, is the kind of man you wish your own kids could learn from- and he teaches a lot more than soccer. One Goal is about so much more than sports. It illustrates how powerful and transcendent teamwork and community can be."Mary Carillo, analyst, NBC Sports

-

"Amy Bass's book transcends sports and provides encouragement in discouraging times."Bill Littlefield, Boston Globe, Best Books of the Year

-

"Wondrous....The players' humble triumphs remind us that no win is too small....One Goal illustrates how sport changed the history of a small town in Maine and connected so many people. It's a relevant tale in today's political climate, where fear and bigotry can be conquered by inclusion, understanding, and the beautiful game."ShireenAhmed, co-host of the Burn It All Down podcast

-

"[A] relevant and rewarding narrative... Bass's effective portrayal of Lewiston as a microcosm of America's changing culture should be required reading."Publishers Weekly

-

"We can use more books that make us feel good about being Americans. This one does that."Lee Miller, The Boston Globe

-

"Bass captures the essence of this unlikely band of brothers perfectly. This isn't a story about a soccer team....More than anything, this is a story of hope. The hope that brought thousands of Africans to a remote corner of the America in search of a better life. The hope that made a city finally open its arms to the children of those immigrants. The hope that our future still might be better than our past."Tom Caron, anchor, New England Sports Network

-

"One Goal is Friday Night Lights for the twenty-first century."Brian Phillips, author of Impossible Owls

-

"The inspirational story of how Somali refugees and native-born white kids in Lewiston, Maine, banded together to win a state championship, helping bridge racial and cultural divides...Bass broadens the story to show how it fits into the story of immigration, racism, Islamaphobia and economic decline in rust belt American towns."The Hollywood Reporter

Newsletter Signup

By clicking ‘Sign Up,’ I acknowledge that I have read and agree to Hachette Book Group’s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use